-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Gerardo D’Amato, Mario Musella, Carolina Bartolini, Lucrezia Borrelli, Alessandra D’Ambrosio, Antonio Franzese, Vincenzo Schiavone, Chiara Bellantone, Chiara Caricato, Mafalda Ingenito, Giant ovarian cyst mimicking no-weight loss after sleeve gastrectomy, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2025, Issue 11, November 2025, rjaf872, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaf872

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Giant ovarian cysts (GOC) are rare due to early ultrasound detection but may reach large dimensions, causing complications. Most are benign mucinous cystadenomas, though borderline or malignant forms exist. A 20-year-old woman, previously submitted to sleeve gastrectomy, presented with acute abdominal pain. Imaging showed a cystic mass measuring 32 × 27 cm, compressing bowel loops and the inferior vena cava. A midline laparotomy was performed with complete excision of the intact mass. Histology confirmed benign mucinous cystadenoma of the left ovary. Recovery was uneventful, and the patient was discharged on Day 3. This case emphasizes the challenges of GOC management in young women and the potential risks of diagnostic delay due to obesity condition. While laparoscopy may be feasible in selected cases, laparotomy is preferred for very large lesions. Fertility preservation, multidisciplinary planning, and surgical strategy are essential. Personalized management allows safe outcomes and fertility preservation in GOC.

Introduction

Ovarian cysts are one of the most common gynecological conditions. However, so-called giant ovarian cysts (GOC) are now a rare clinical entity, as ovarian lesions are generally diagnosed and treated before they reach extreme dimensions. There is no clear consensus on the definition: some series define "giant" cysts as those >10 cm, while others use cut-offs of 15 or 20 cm, or refer to abdominal distension beyond the umbilicus [1].

Giant masses are most often benign mucinous or serous cystadenomas; however, the risk of borderline or malignant neoplasia is significant [2, 3]. Patients may present with mass-effect symptoms (distention, abdominal pain, changes in bowel movements, or urination) or acute complications such as torsion, rupture, and hemoperitoneum [4, 5].

Diagnosis is primarily based on transvaginal and abdominal ultrasound, with possible support of computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in complex cases or to define anatomical relationships. The International Ovarian Tumor Analysis (IOTA) criteria and the Assessment of Different Neoplasias in the adneXa (ADNEX) model improve the discrimination between benign and malignant lesions [6]. Serum markers such as CA-125 and HE4 have a complementary role, particularly in the selection of patients to be referred to gynecological oncology centers [7].

Treatment is almost always surgical; laparoscopy is now feasible even for large masses, with benefits in terms of postoperative pain and functional recovery, but requires controlled decompression techniques to avoid spillage [8, 9]. Laparotomy remains indicated in the presence of suspected cancer or when the size/adhesions make the minimally invasive approach risky [10].

Case report

A 20-year-old woman with no significant comorbidities, who had undergone a sleeve gastrectomy 4 years earlier for severe obesity (BMI 42 kg/m2), presented to the emergency room with episodes of acute, severe abdominal pain that had been on for several hours. On physical examination, the abdomen appeared globular and tense, with evident distention predominantly on the left side. It was non-tender to superficial palpation but with moderate, diffuse deep tenderness. There were no signs of peritoneal irritation or palpable, well-demarcated masses; peristaltic sounds were normal.

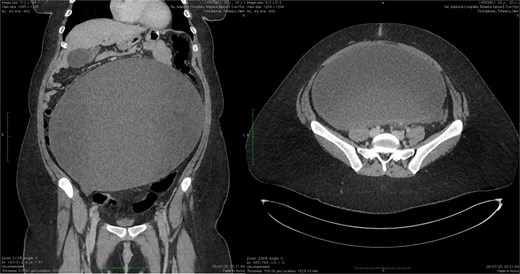

Abdominal ultrasound revealed a large, anechoic mass, apparently multicompartmental, located predominantly on the left side but also extending to the pelvis. A subsequent abdominal CT scan with contrast revealed a large cystic mass measuring approximately 32 × 27 cm, presumably originating from the adnexal region, extending from the mesogastric region to the pelvis. The lesion caused compression on the small intestinal loops, located in the epigastric region but without signs of occlusion, and significant compression of the infrarenal inferior vena cava. No free effusion or signs of metastasis were detected (Fig. 1).

CT scan showing ovarian cyst compressing the small bowel in the epigastrium (longitudinal and transversal section).

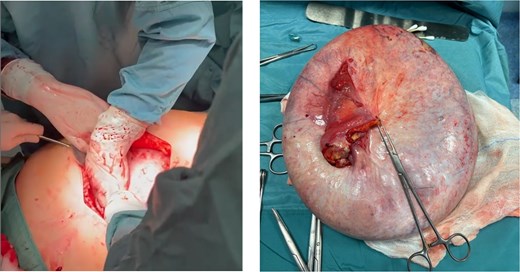

Given the symptoms, the exceptional size of the mass, and the radiological findings, the patient underwent open surgery, considering the previous surgical procedure which could have caused adhesions, through a median incision of ~20 cm. Upon opening the abdominal cavity, a thin-walled, multicompartmentalized cystic mass of left ovarian origin was discovered, occupying almost the entire abdominal and pelvic cavity. After careful isolation of the lesion, a cystectomy was performed with complete removal without intraoperative rupture and minimal blood loss (Fig. 2). The contralateral ovary appeared to be of regular morphology and size.

(a) Mini-laparotomy (about 25 cm) for removal of the lesion. (b) Intact surgical specimen.

The final histological examination documented a benign mucinous cystadenoma of the left ovary, without evidence of atypia or borderline/malignant components.

The postoperative course was uneventful, with recovery of intestinal canalization on the second day and discharge on the third post-operative day in good general condition.

Discussion

The case described fits into the literature on GOC, which, despite being rare, poses significant diagnostic and therapeutic challenges. Mucinous cystadenomas are the most frequently associated with exceptional volumes. [2] Borderline and malignant tumors, however, represent 10%–20% of cases, a percentage sufficient to justify a thorough onco-gynecological evaluation.

Patients typically present with significant abdominal distension, sometimes mistaken for obesity or ascites. In fact, in this case the patient, despite the previous sleeve gastrectomy was still in an high stage of obesity (39 kg/m2) and this could have been the reason of diagnostic delay. Certainly, the lesion was not present at the moment of the surgical bariatric procedure (sleeve gastrectomy) that was performed in 2021. At the same time is reasonable to assume that the lesion developed over time but, just one month earlier the surgery, the patient referred abdominal pain. Thanks to these symptoms the patient discovered her problem. The pain may result from capsular stretching, torsion, or visceral compression. Cases of urinary retention, intestinal obstruction, and even thromboembolic complications due to venous stasis have been described [4, 5].

Ultrasound remains the first-line diagnostic method. The application of the IOTA criteria (Simple Rules, ADNEX model) achieves an accuracy >90% in the benign/malignant distinction [11]. CT or MRI are particularly useful in giant masses to evaluate the anatomical relationships, the presence of ascites or metastases and to plan the surgical approach [6]. The markers CA-125 and HE4, although with specificity limits, support preoperative stratification, especially in post-menopausal women [7].

Laparoscopy for giant cysts has been widely described as feasible and safe in selected cases [9]. Techniques used included supraumbilical or xiphoid trocar access or intraoperative decompression via endoscopic bag aspiration or mini-laparotomy. It’s important to be careful to hemodynamic instability after rapid emptying of masses >10–15 kg.

Comparative studies as Wang et al. 2021 show significant advantages in terms of hospital stay and recovery, with no increase in recurrences or complications when appropriate selection is made [12]. However, laparotomy remains the standard of care in the presence of suspected cancer, the need for staging, or excessively large masses [10].

In young or adolescent patients, the goal is ovarian preservation, when possible. The laparoscopic approach is associated with a lower impact on fertility and a shorter hospital stay [13]. During pregnancy, management requires a multidisciplinary team: the second trimester is preferred for possible surgery, reserved for symptomatic, complicated or suspicious masses [14].

Conclusion

GOC are now a clinical rarity, but they can still present with massive symptoms or serious complications. The literature emphasizes the importance of a multidisciplinary and personalized approach thorough preoperative stratification with imaging and biomarkers, choice of the type of surgical procedure (laparoscopy vs. laparotomy) based on oncological risk and technical feasibility and attention to fertility preservation in young patients.

The reported case adds to existing evidence, helping to underscore the importance of early diagnosis and safe, targeted surgical strategies.

While the surgical management of GOC follows established standards, we believe this case highlights some important and less frequently reported aspects; obesity masking the presence of a large abdominal lesion: despite undergoing bariatric surgery, the patient remained in a high obesity range (BMI 39 kg/m2 at presentation). The persistence of abdominal distension was initially attributed to insufficient weight loss rather than to the presence of a growing intra-abdominal mass. This likely contributed to a diagnostic delay.

Although the patient underwent sleeve gastrectomy, the expected postoperative weight reduction was limited due to the presence and progressive growth of the ovarian cyst, which contributed to abdominal volume and hindered the perception of effective weight loss.

This case suggests that in obese patients, particularly those undergoing bariatric procedures, persistent or disproportionate abdominal distension should prompt careful imaging assessment, as obesity itself can mask significant intra-abdominal pathology, reinforcing the need for awareness of gynecological causes of abdominal distension in obese and post-bariatric patients, to avoid delays in diagnosis and treatment.

Conflict of interest statement

None of the authors have any conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding

No external funding was received for this study.

Ethical approval

We did not require ethical approval from our EC (Campania 3, Naples, Italy) for case reports.

Consent

The patient provided informed written consent.