-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Yavor Asenov, Boris Kunev, Todor Yanev, Branimir Golemanov, Plamen Getsov, Nikolay Penkov, When free air misleads: pneumoperitoneum from a ruptured pyogenic liver abscess, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2025, Issue 11, November 2025, rjaf867, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaf867

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Pyogenic liver abscess (PLA) is a severe condition with mortality rates of 10%–19%. Spontaneous rupture occurs in about 5% of cases and carries much higher mortality. Rarely, ruptured PLA presents with pneumoperitoneum, mimicking hollow viscus perforation. We report a 48-year-old man with chronic gastric ulcer disease who presented with fever, malaise, nausea, and abdominal distension two weeks after endoscopic hemostasis. He rapidly deteriorated with septic shock and peritoneal signs. Ultrasound was inconclusive, and repeat X-ray revealed pneumoperitoneum. Laparotomy found purulent peritonitis from a subcapsular abscess in segment II, perforating both diaphragmatic and visceral hepatic surfaces. Enterococcus faecalis was isolated, and antibiotics administered. A secondary abscess in segment VII was later drained percutaneously. The patient recovered after 37 days. This case highlights the diagnostic challenge of ruptured PLA and the value of combined surgical and minimally invasive management.

Introduction

Pyogenic liver abscess (PLA) is an uncommon but serious infection with mortality rates of 10%–19% [1]. Risk factors include diabetes, biliary disease, cirrhosis, and malignancy [1]. The most frequent pathogens are Klebsiella pneumoniae and Escherichia coli, while Enterococcus faecalis is rarely reported [1, 2]. Spontaneous rupture of PLA occurs in approximately 3.8%–5.4% of cases [3, 4]. Mortality is substantially higher than in non-ruptured PLA, with historical reports up to 43.5% [4], although outcomes have improved in recent series with prompt surgical intervention [3]. Ruptured PLA may present with pneumoperitoneum and peritonitis, mimicking perforated hollow viscus [1, 5].

Here, we report a rare case of ruptured PLA caused by E. faecalis, initially misdiagnosed as perforated gastric ulcer, emphasizing the diagnostic challenges and the importance of combining open and minimally invasive management.

Case presentation

A 48-year-old male with known gastric ulcer disease and no other comorbidities was admitted to a surgical clinic with upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Endoscopy revealed a stable coagulum at the fundus–corpus junction and a 10–12 mm anterior wall ulcer with a retracted visible vessel (Forrest IIa–IIb), treated with injection hemostasis. The patient remained stable and was discharged on day 4.

Forty-eight hours later, he presented to the emergency department with fever up to 40°C, malaise, nausea, and abdominal fullness without vomiting or abdominal pain. He denied gastrointestinal bleeding. Laboratory tests revealed leukocytosis of 21 × 109/L with 87% neutrophils, hemoglobin 106 g/L, bilirubin 24/17 μmol/L, AST 204 U/L, ALT 262 U/L, CRP >32 mg/dl, and D-dimer 6121 ng/ml.

On admission, no peritoneal irritation was evident. Abdominal ultrasound showed a normal right hepatic lobe, while assessment of the left lobe was limited by bowel gas. The initial abdominal X-ray was unremarkable.

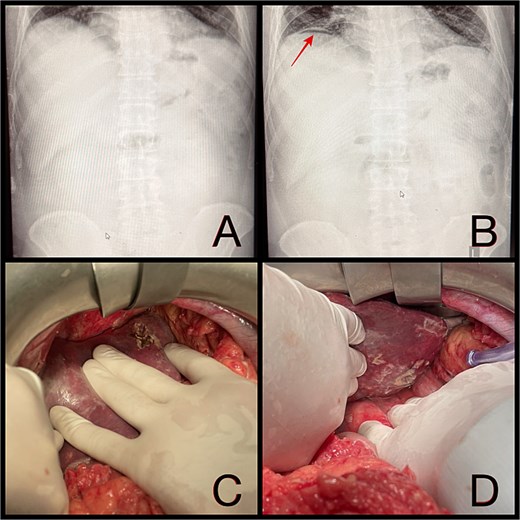

Within 2 hr of admission, the patient’s condition deteriorated rapidly, developing septic shock and peritoneal signs. Repeat abdominal X-ray revealed free subdiaphragmatic air. Given the acute deterioration and new findings, urgent laparotomy was indicated for suspected gastric perforation.

Intraoperatively, a ruptured liver abscess in segment II was found, perforating both the diaphragmatic and visceral hepatic surfaces. There was purulent discharge into the peritoneal cavity, predominantly in the upper abdomen. No gastrointestinal perforation was identified. Abdominal lavage, liver biopsy, and drainage were performed, followed by laparostomy (Fig. 1).

(A and B) Abdominal radiographs showing progression from no free gas (A) to a crescent of pneumoperitoneum beneath the right hemidiaphragm (B, arrow) within 2 hr. (C and D) Intraoperative findings of a ruptured pyogenic liver abscess in segment II, perforating both the diaphragmatic and visceral hepatic surfaces.

At second-look laparotomy after 48 hr, lavage demonstrated marked improvement. Five drains were placed and the abdomen was closed (laparosynthesis). Microbiological cultures isolated E. faecalis. Antibiotic therapy was tailored accordingly, starting with intravenous levofloxacin 500 mg twice daily.

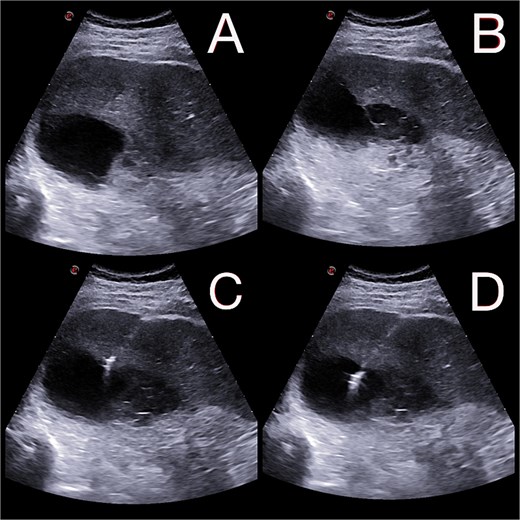

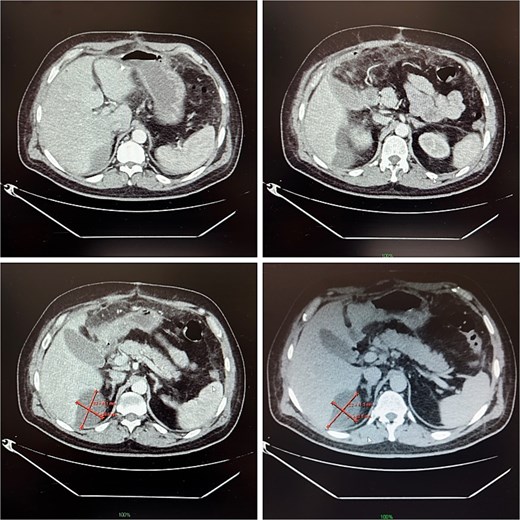

On postoperative day 14, the patient remained febrile. Computed tomography revealed a secondary abscess in segment VII (Fig. 2), which was successfully managed by percutaneous drainage under ultrasound guidance (Fig. 3). The regimen was subsequently switched to intravenous linezolid 600 mg twice daily, combined with antifungal therapy. The drains were gradually removed by postoperative day 30, while intravenous therapy continued until day 35. The patient was discharged on day 37.

(A and B) Abdominal ultrasound depicting a 9 × 5 cm abscess in segment VII. (C and D) Percutaneous drainage performed with placement of a 10 Fr catheter under ultrasound guidance.

Contrast-enhanced abdominal CT on postoperative day 14, demonstrating a 9 × 5 cm abscess in segment VII.

Discussion

Rupture of PLA is infrequent but associated with worse outcomes. While historical series reported mortality up to 43.5%, recent cohorts describe improved survival rates (as low as ~4%) with prompt surgical management [3, 4].

Risk factors for rupture include large abscess size (>6 cm), cirrhosis, gas-forming organisms, and subcapsular or left-lobe location [3]. Wang et al. [6] identified diabetes and biliary disease as dominant risk factors for PLA.

In our patient, the abscess was located subcapsularly in the left lobe—a frequent risk factor for rupture—but exceptionally, it penetrated both diaphragmatic and visceral hepatic surfaces, a finding rarely documented in the literature. Enterococcal PLA is increasingly reported and has been associated with significantly higher treatment failure and mortality [7]; gas-forming PLA remain classically linked to K. pneumoniae [2]. Rarely, Enterococcus species have been implicated in gas-containing abscesses in other sites [8], making the etiology of our case unusual.

Possible mechanisms include bacterial translocation following gastric ulcer bleeding and endoscopic hemostasis, iatrogenic seeding via endoscopic equipment (as Enterococcus is known to persist in biofilms), or secondary biliary contamination. This underlines the importance of microbiological sampling and targeted therapy.

The diagnostic challenge was substantial. Pneumoperitoneum is most often caused by hollow viscus perforation [1]. In this case, repeat X-ray demonstrated free air, and urgent laparotomy was indicated. Similar misdiagnoses of ruptured PLA as gastric perforation have been described [5, 9]. Non-surgical treatment of ruptured PLA has been reported in selected stable patients without diffuse peritonitis [10, 11]. However, in cases presenting with septic shock and peritonitis, as in our patient, emergency laparotomy remains mandatory. Older age has been associated with prolonged hospitalization in PLA [12].

Spontaneous rupture can also extend toward atypical sites, such as the abdominal wall, forming secondary collections [13]. The subsequent development of a secondary abscess in segment VII in our case emphasizes the importance of close postoperative imaging. Multifocal disease or incomplete drainage are possible mechanisms, despite negative ultrasound findings in the right lobe and two-stage abdominal lavage. Management depends on the clinical scenario. In cases with diffuse peritonitis and septic shock, urgent laparotomy with lavage and drainage is required [3]. In stable patients with liver abscesses, including selected cases of localized rupture, percutaneous catheter drainage plus antibiotics can be effective [14]. In our patient, a hybrid approach—emergency laparotomy followed by percutaneous drainage of a secondary abscess—proved successful and reflects the modern trend of integrating open and minimally invasive therapies.

The patient recovered after 37 days. This case highlights the diagnostic challenge of ruptured PLA and the importance of combined surgical and minimally invasive management.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Funding

The authors declared that this study has received no financial support.

Informed consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images.

Ethics committee approval

Ethical approval was not required for this single case under our institutional policy.