-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Maria Albuquerque, Cláudia Constantino, Pedro Martins, Diogo Casal, Functional shoulder girdle reconstruction in paediatric desmoid tumour, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2025, Issue 10, October 2025, rjaf830, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaf830

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Desmoid tumours are rare fibroblastic neoplasms that, although benign, may be locally aggressive, invasive, and disabling. In children with Gardner syndrome, they typically arise in the abdominal wall, whereas scapular involvement is uncommon and surgically challenging because of the risk of scapular winging after resection of stabilizing muscles. We report the case of a 4-year-old boy with Gardner syndrome and multifocal desmoid disease, including a large tumour of the left shoulder girdle. Radical resection required sacrifice of several stabilizers, and scapular stability was preserved using a dynamic reconstructive technique: a trapezius flap elongated with lumbosacral fascia, passed through a bone tunnel in the scapula and anchored to adjacent muscles. Despite recurrence requiring re-excision and chemotherapy, the patient remained disease-free at 4-year follow-up, with preserved scapular stability. This case underscores the importance of dynamic reconstruction techniques, avoidance of mutilating resections, and multidisciplinary management in paediatric multifocal desmoid disease.

Introduction

Desmoid tumours (DTs) are rare fibroblastic neoplasms belonging to the fibromatosis group. Despite being histologically benign and lacking metastatic potential, they are characterized by infiltrative growth, high recurrence rates, and the potential to cause severe morbidity through local invasion and impairment of function [1, 2].

Gardner syndrome (GS), a variant of Familial Adenomatous Polyposis (FAP), results from mutations in the APC gene and is characterized by multiple colorectal adenomas and extracolonic manifestations such as osteomas, epidermoid cysts, and DTs [3]. DTs affect 3.5%–5.7% of GS patients, most commonly arising in the abdominal wall or intra-abdominal cavity [4]. Extra-abdominal locations, such as the shoulder girdle, are rare [5].

Surgical treatment is often part of the therapeutic approach, but resections should be carefully planned, as mutilating procedures may not be justified given the benign nature of the disease. Resection in the scapular region may require sacrifice of key stabilizing muscles, carrying a high risk of postoperative scapular winging and upper limb dysfunction.

We present the case of a 4-year-old boy with GS and multifocal, rapidly progressive desmoid disease, including a large scapular tumour. We describe a dynamic scapular stabilization technique that preserved shoulder function following wide excision.

Case report

A 4-year-old boy presented with multiple soft-tissue masses first noted at 2 months of age, involving the left shoulder girdle, lumbar region, scalp and upper limbs. Initial magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) demonstrated an infiltrative lesion in the left scapular region measuring 5 × 3.5 × 1.5 cm, together with smaller nodules. Biopsy confirmed the diagnosis of desmoid-type fibromatosis. Given the early onset and multifocal disease, APC mutation testing was performed and confirmed a de novo pathogenic mutation, establishing the diagnosis of Gardner syndrome. Neither parent carried the mutation.

The patient remained under regular surveillance by the Paediatrics team at the Portuguese Institute of Oncology, undergoing periodic imaging studies. At the age of 4 years (2021), MRI showed rapid enlargement of the scapular mass to 12 × 6.8 cm with intercostal infiltration, along with growth of the lumbar lesion. Surgery was undertaken 4 months later, with wide excision of both tumours (Figs 1 and 2).

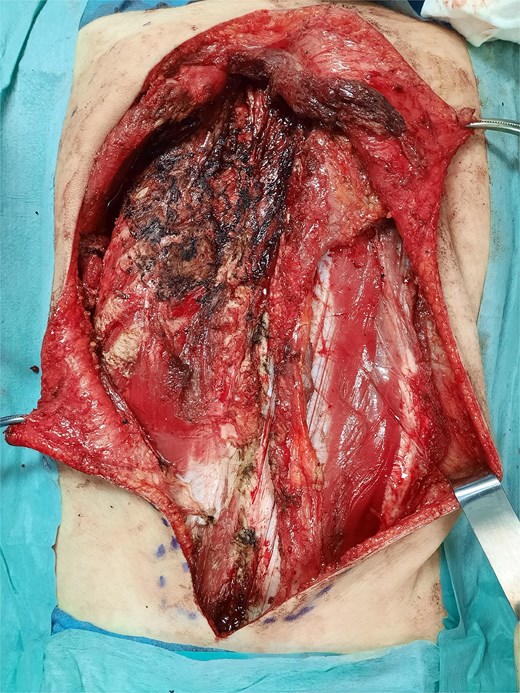

The scapular resection required partial removal of the erector spinae, serratus posterior superior, rhomboid major and minor, serratus anterior, and latissimus dorsi muscle (Fig. 3).

Post-resection defect in the scapular region showing loss of stabilizing muscles.

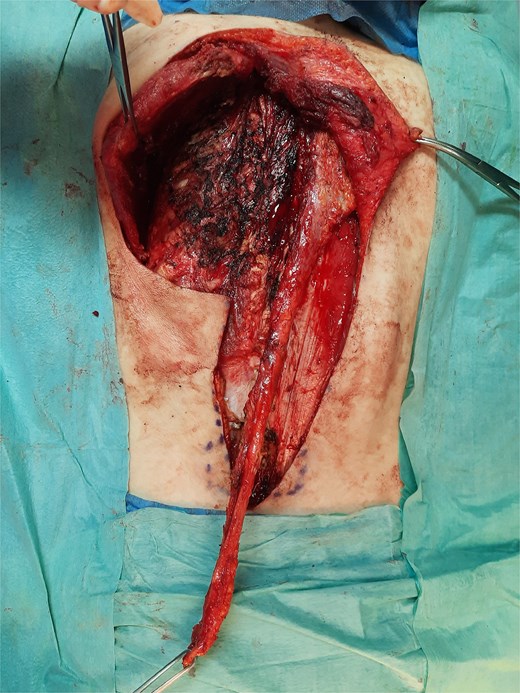

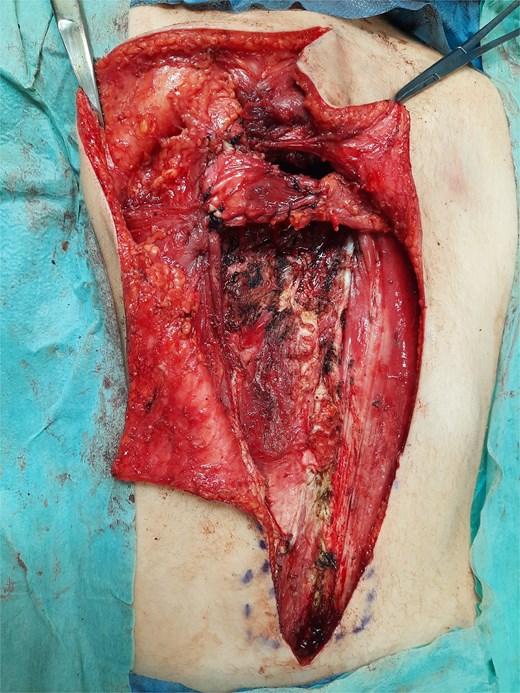

Reconstruction involved a dynamic stabilization of the medial scapular border using a trapezius muscle flap elongated with a strip of lumbosacral fascia (Fig. 4). A bone tunnel was created in the medial aspect of the infraspinous scapular region, and the flap was folded and sutured onto itself, as well as to the remnants of the trapezius, latissimus dorsi, and serratus anterior muscles (Fig. 5). Haemostasis was achieved, and fibrin glue was applied. Four suction drains were placed, and the wound was closed in layers. The left scapula was immobilized postoperatively with an orthosis.

Trapezius muscle flap elongated with a strip of lumbosacral fascia.

Inset of the flap after passage through bone tunnel and fixation.

Postoperatively, the child developed oedema and a urinary tract infection with Proteus mirabilis, treated conservatively. Drains were removed under sedation 15 days postoperatively, and the patient was discharged, with regular follow-up in the Plastic Surgery clinic.

Histopathology confirmed the diagnosis of desmoid-type fibromatosis (775 g, 17 × 13 × 8 cm), with tumour tissue noted adjacent to the surgical margins.

During follow-up, the patient developed a seroma, which required repeated drainage during outpatient visits up to 3 months postoperatively. At 4 months, the orthosis was removed, and the patient showed no signs of scapular winging.

At 18 months, the patient developed a local recurrence in both scapular and lumbar areas. A second surgical excision was performed 4 months later, again with positive surgical margins. Given the multifocality and rapid regrowth, systemic therapy with weekly vinblastine and methotrexate was initiated.

At the 4-year follow-up, the patient had discontinued chemotherapy, with no evidence of recurrence. Scapular stability was preserved, without winging, and upper limb function remained good (Fig. 6).

Four-year postoperative result showing preserved scapular stability without winging.

Discussion

GS is an autosomal dominant condition considered a variant of FAP, as both result from mutations in the APC gene, with ~20% arising de novo, as was the case in our patient [3]. Around 2% of all DT are FAP-associated [6].

Whilst 37%–50% of DTs occur in the abdominal region, extra-abdominal locations are less common, with the shoulder girdle, chest wall, and inguinal region being the most frequently affected [3]. Amongst extra-abdominal locations, the shoulder girdle shows higher progression rates, often justifying an interventional approach [7].

These tumours, although benign, may be locally invasive and functionally disabling. For this reason, surgery should avoid unnecessarily mutilating resections. In multifocal and rapidly progressive cases, systemic therapy is often required in addition to surgery, as in our patient.

Several scapular stabilization techniques have been described. Scapulopexy involves fixation of the scapula to the rib cage using metal wires without arthrodesis, with positive results in patients with fascioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy [8]. Muscle transfer techniques like the modified Eden Langer method, which transfers the levator scapulae and rhomboid muscles to restore the function of a paralyzed trapezius, have also been employed [9].

In our case, wide excision required the partial removal of key stabilizing scapular muscles, including portions of the serratus anterior, trapezius and rhomboid major and minor. Scapular winging was successfully prevented through a dynamic stabilization technique involving a trapezius muscle flap elongated with a strip of lumbosacral fascia, passed through a bone tunnel in the scapula and anchored to residual muscular structures. This technique provided medial stabilization of the scapula and functionally compensated for the loss of native stabilizers.

At 4 years postoperatively, the patient demonstrated stable scapular positioning and normal shoulder girdle function, with no clinical evidence of winged scapula. This favourable outcome highlights the efficacy of the reconstructive approach used. Importantly, the case also illustrates that multifocal, rapidly progressive desmoid disease requires multimodal therapy and close collaboration of a multidisciplinary team including surgery, oncology and genetics.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Funding

None declared.