-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Peter Tilleard, Eshwarshanker Jeyarajan, The band’s encore: scarring causing dysphagia post-gastric band removal, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2025, Issue 1, January 2025, rjaf028, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaf028

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Placement of a laparoscopic adjustable gastric band (LAGB) is a procedure used in bariatric surgery. Despite its decrease in popularity due to its high reoperation rate and suboptimal clinical response, managing the complications of LAGBs remains an important component of general and bariatric surgeons’ work. Only two case studies describe return to theatre to excise scarring, which has continued to cause symptoms after LAGB removal. We report the case of a 72-year-old female presenting with persistent dysphagia nine years post removal of her LAGB. Laparoscopic excision of a fibrotic scar at the site of her previous LAGB resulted in complete resolution of her symptoms. This case report draws attention to the possibility of ongoing symptoms from scarring despite LAGB removal and how this can be managed. Further, it may suggest the importance of dividing a fibrotic scar found under a LAGB on removal.

Introduction

Placement of a laparoscopic adjustable gastric band (LAGB) is a procedure used in metabolic bariatric surgery that has been associated with suboptimal clinical response and complications requiring reversal [1]. Due to this, the procedure’s popularity has decreased; however, managing the complications of LAGBs remains an important component of bariatric and general surgeons’ work [1, 2].

LAGB surgery is a restrictive procedure in which an adjustable band is placed around the upper stomach partitioning it and creating a functional pouch outlet. This functional pouch outlet can be adjusted by injecting or aspirating fluid in the connected superficially placed port. The first LAGB surgery was performed in 1993; prior to this, open techniques had been in use since 1983 [3, 4]. LAGB surgery was hailed as a breakthrough in bariatric surgery by its initial proponents for its minimally invasive technique, adjustability, and reversibility [3].

LAGB surgery became a popular option in the management of severe obesity, especially in Europe. A 2003 study suggested that it made up 80% of bariatric procedures in France [5]. Since then LAGB surgery has seen a dramatic reduction in popularity; the 2016 International Federation for the Surgery of Obesity and Metabolic Disorders (IFSO) worldwide survey reported that adjustable gastric banding (AGB) operations made up only 3% of all bariatric operations [1]. The IFSO worldwide survey released in 2024 reported that AGB surgery represented only 0.8% of global bariatric surgery performed (5010 cases globally) [2]. The report concluded that AGB surgery may become a procedure of solely historical importance [2]. This reduction in popularity has been due to poorer long-term results compared to alternative procedures and the high rate of reoperation required [1].

A systematic review and meta-analysis published in 2009 highlighted the underperformance of LAGB surgery compared to alternative bariatric procedures. The study showed that gastric banding resulted in a mean of 46.2% excess body weight loss (%EBWL) [6]. This was the lowest loss of the compared procedures, the greatest loss being achieved with biliopancreatic diversion/duodenal switch procedures (63.6% EBWL) [6]. Further, the study reported that in type two diabetic patients, disease resolution was achieved in only 56.7% of patients who underwent LAGB surgery compared to 79.7% of gastroplasty patients, 80.3% of gastric bypass patients, and 95.1% of biliopancreatic diversion/duodenal switch patients [6].

Long-term complications of LAGBs include band slippage, band erosion, oesophageal dilation, obstruction, and port site issues. A large study with long-term follow-up showed that 49.9% of bands had been removed at 15 years post insertion [7]. The most common reason for removal was inadequate weight loss, followed by food intolerance with or without reflux [7]. The study reported that 5% of patients suffered a band slippage or pouch dilation, and 4.7% of patients had intragastric band migration [7]. Almost 60% of patients underwent at least one subsequent operation, whether this was for reversal, conversion to another bariatric procedure, or complication of the port site [7]. Another 2016 study reported that 84.4% of patients had experienced at least one complication of their LAGB at the 13-year follow-up [8].

A 2014 Cochrane review showed that LAGB surgery achieves less long-term weight loss than other bariatric procedures and is associated with a higher rate of reoperation [9].

Clinical cases of scarring of the gastric wall secondary to LAGB have been reported in the literature [10–12]. A 2006 histologic study showed that LAGBs commonly cause severe fibrosclerosis of the gastric wall under the band [13]. A 1991 study reported the results of 16 full thickness gastric wall biopsies post gastric band removal [14]. Of the 16 biopsies, serosal fibrosis was seen in 15 cases; of these, the fibrosis extended into the muscularis propria in four cases [14].

Case reports of persistent gastric stenosis due to LAGB-induced gastric scarring support the consideration of dissection of scarring seen at the time of LAGB removal [10, 11]. Only two case studies describe return to theatre to excise scarring, which has continued to cause gastric obstruction after LAGB removal [10, 12].

Case report

We report the case of a 72-year-old female referred to our clinic with persistent dysphagia nine years post removal of her LAGB.

She underwent a barium swallow examination, which showed a residual indentation and barium hold-up at the cardia of her stomach in the position of her previous LAGB. It also showed a small sliding hiatus hernia and extensive abnormal tertiary contraction waves in the middle and lower third of the oesophagus. She had high-resolution oesophageal manometry, which was unremarkable.

The small hiatus hernia was also seen on a computed tomography (CT) scan of her chest, abdomen, and pelvis. Importantly, this CT also illustrated a rim-like calcification around her proximal stomach in the position of her previous gastric band.

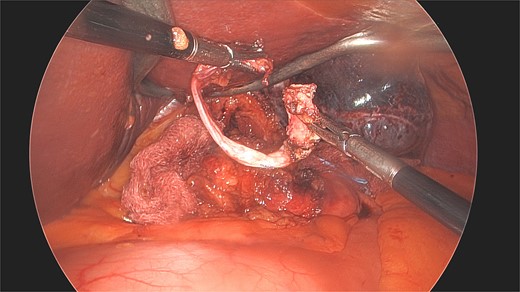

On laparoscopy, a fibrosed scar capsule was found densely adherent to her proximal stomach. This was uneventfully divided and excised (Fig. 1). On examination, no remnant gastric band was evident in the specimen. During the same laparoscopic surgery, her small hiatus hernia was repaired uneventfully.

Laparoscopic view of the excised scar dissected from the stomach nine years post the removal of the patient’s LAGB.

She recovered quickly and was discharged from the hospital the following day. The patient was subsequently seen in the outpatient clinic at 6 weeks post her operation. At this point, she reported complete resolution of her dysphagia symptoms and astounding improvement in her quality of life.

Discussion

LAGB surgery has been shown to have poorer weight loss outcomes in comparison to other bariatric surgery options and a high rate of reoperation due to complications [1]. For these reasons, it has seen a dramatic decrease in popularity [1, 2]. While LAGB surgery may become a historical operation, management of its various complications remains important work of bariatric and general surgeons.

Here, we present the case of a rare complication caused by a LAGB despite its removal. The scar excision in this case resulted in complete resolution of the patient’s symptoms, which had persisted for close to a decade post removal of her LAGB.

This case report draws attention to the possibility of ongoing symptoms from scarring despite LAGB removal and demonstrates how this can be managed. It also shows the importance of dividing a gastric fibrotic scar if found under a LAGB on removal.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Funding

None declared.