-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Aldin Malkoc, Maryam Ahmad, Paul Kim, Iden Andacheh, Treatment of metastatic carotid body paraganglioma in a young female, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2025, Issue 1, January 2025, rjae811, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjae811

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Carotid body tumors (CBTs) are rare head and neck paragangliomas that arise from the carotid body chemoreceptor at the common carotid bifurcation. These neoplasms are generally benign, slow-growing, nonsecreting, and well-vascularized. Metastasis occurs in ~5% of cases. Here, we report a case of a 35-year-old female presenting with 1-year history of a growing left neck mass, consistent with a CBT. Patient ultimately underwent surgical excision and was found to have a malignant paraganglioma with metastases to cervical lymph nodes. She was further treated with a left modified radical neck dissection and adjuvant radiotherapy and remains disease-free at the time of follow-up 2 years later. We discuss the roles of preoperative assessment, concomitant selective neck dissection and tumor resection, and subsequent modified radical neck dissection as part of the diagnosis and surgical management of malignant CBTs.

Introduction

Carotid body tumors (CBTs) are rare head and neck paragangliomas that arise from the carotid body chemoreceptor at the common carotid bifurcation [1]. The reported incidence of CBTs is 1–2 per 100 000 [2]. These neoplasms are generally benign, slow-growing, nonsecreting, and well-vascularized [1]. Metastases occur in ~5% of cases, usually as regional metastases to cervical lymph nodes and infrequently to distant sites [3]. Here, we report a case of a 35-year-old female presenting with 1-year history of a growing left neck mass, consistent with a CBT, who underwent surgical excision and was found to have a paraganglioma with metastases to cervical lymph nodes. She was further treated with a left modified radical neck dissection and adjuvant radiotherapy, and remains disease-free at the time of follow-up 1 year later. We discuss the roles of a careful preoperative assessment, concomitant selective neck dissection (SND) and tumor resection, and subsequent modified radical neck dissection as part of the diagnosis and surgical management of malignant CBTs.

Case presentation

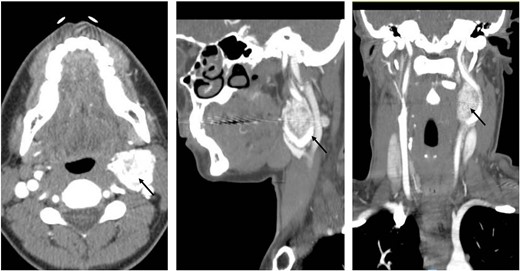

A 35-year-old woman presented with a 6-month history of a progressively enlarging, painless left neck mass. She reported no additional symptoms, including no fevers, night sweats, unexplained weight loss, hoarseness, or dysphagia. She had no significant past medical or family history and did not take any medications. Physical exam revealed a 3-cm well-circumscribed, hard, immovable, and nontender mass on the left lateral neck and no additional abnormalities. A CT scan of the neck and chest was ordered, which revealed a lobulated left cervical mass measuring up to 3.6 cm (Fig. 1). The patient was referred to vascular surgery for further evaluation.

Coronal, sagittal, and axial images showing the 3.6 × 3.5 cm mass splaying the left internal and left external carotid arteries.

A preoperative CTA of the head and neck was done, which revealed a 3.9 × 2.9 × 2.7 cm hypervascular mass centered between the proximal internal and external carotid artery (ECA). The mass completely encased the left ECA and partially (~180°) encased the left internal carotid artery (ICA). Based on these findings, the tumor was classified as category Shamblin II. There were no preoperative hormone labs ordered as in our institution. We do not routinely check for CBTs.

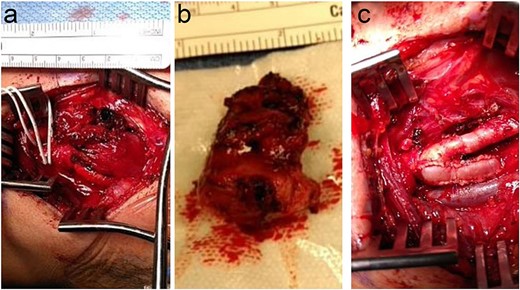

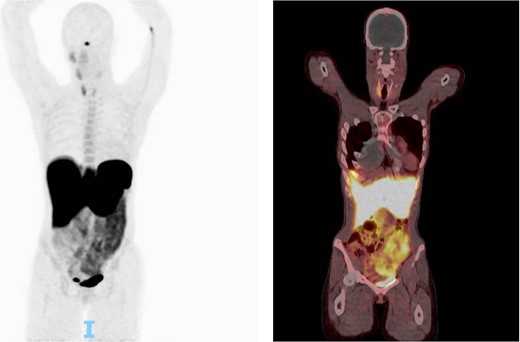

A transverse neck incision was used at the surgical approach of choice. At the posterior aspect of the left carotid bifurcation, the tumor was densely adherent to the arterial wall, and a portion of the carotid wall was taken with the tumor (Fig. 2). The patient tolerated the procedure well and had an uneventful postoperative course. She began a 2-week course of clopidogrel and a 3-month course of aspirin to prevent complications associated with the ICA repair. Pathology revealed a paraganglioma that demonstrated loss of succinate dehydrogenase B (SDHB) expression and stained positive for synaptophysin and S100. The patient was referred for genetic testing, which identified a pathogenic SDHB variant associated with hereditary paraganglioma-pheochromocytoma syndrome. She additionally underwent a PET scan, which revealed a left level II-B lesion (Fig. 3), consistent with metastatic neuroendocrine disease.

(a) Left neck exposure showing the adhered carotid body tumor. (b) Once the tumor was excised. (c) After patch angioplasty occurred.

One hour after 5.4 millicurie of fludeoxyglucose injected this shows a CT scan followed up by PET scan. No suspicious focal activity was noted. Physiologic activity was noted in the right parotid/salivary glands minimally on the left mandibular gland, and bilateral thyroid, more on the right thyroid. Otherwise, no abnormal uptake was noted in the left neck. Presumed postop changes were seen in the left neck.

Three months after initial tumor resection, the patient underwent a left modified radical neck dissection. Pathology revealed metastatic paraganglioma. The patient’s case was discussed at the multidisciplinary tumor board, and adjuvant radiotherapy was recommended to reduce the risk of recurrence. The patient received 60 Gy in 30 fractions to the left neck. At 1-year follow-up, the patient has had no complaints and is continuing follow-up with annual surveillance.

Discussion

Malignant CBTs are rare, occurring in ~5% of cases. There are no clear histopathological distinctions between benign and malignant CBTs; thus, malignancy is typically established based on the presence of metastasis. The most common site of metastasis is cervical lymph nodes, but distant metastasis to sites such as lung, bone, and liver can also occur [4]. MCBTs tend to have an insidious clinical course and can recur or metastasize to distant sites years after diagnosis.

In the absence of known metastasis, preoperative assessment cannot distinguish between benign and malignant CBTs [4]. However, certain imaging and clinical characteristics may suggest malignancy and warrant a more extensive workup prior to surgical resection [5]. In their retrospective case series, Gu et al. found that malignant CBTs were associated with a larger tumor size and a Shamblin class of II or III [6]. Similarly, Cho et al. [6] found that malignant pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas were associated with a tumor size greater than 6 cm (HR 2.43, 95% CI 1.06–5.56). Our patient’s maximal tumor diameter was 3.9 cm, which was not large enough to raise suspicion of malignancy. However, she had other clinical characteristics that suggested a possibility of malignancy, including her relatively young age of 35 and tumor classification as Shamblin group II.

While our patient did not undergo a concomitant SND, lymphatic tissue along the jugular chain was resected while exposing the tumor and included in the pathologic analysis. This tissue was negative for metastasis. Malignancy was determined based on the presence of metastasis in lymph nodes that were adherent to the tumor. Additionally, a transverse neck incision may be advantageous in performing CBT surgery; if malignancy is detected, the same incision can be used to perform ipsilateral neck dissection [7]. Our experience suggests that an SND is not necessary for detecting nodal metastasis, and excision of lymph nodes encountered during exposure and dissection of the tumor might be sufficient [8, 9]. However, SND is likely still useful, particularly if patients have risk factors for malignancy [8]. Furthermore, it could have prevented the need for a subsequent modified radical dissection in our patient.

Although surgery is the primary therapy for both benign and malignant CBTs, adjuvant radiotherapy has been recommended for local disease control and/or to decrease the likelihood of recurrence. In our patient, adjuvant radiotherapy to the left postoperative bed was used to decrease the likelihood of recurrence and eliminate any residual disease. Since she was found to have a pathogenic SDHB variant on genetic testing, we felt a more aggressive treatment approach of both a modified radical neck dissection and radiotherapy was warranted. At 1-year follow-up, the patient is doing well with no evidence of disease.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare there is no conflict of interest.

Funding

The research presented in this manuscript had no specific funding from any agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

- carotid body paraganglioma

- chemoreceptor cells

- cognitive-behavioral therapy

- follow-up

- neoplasm metastasis

- paraganglioma

- radiotherapy, adjuvant

- surgical procedures, operative

- carotid body

- diagnosis

- neoplasms

- neck mass

- preoperative medical evaluation

- modified radical neck dissection

- selective neck dissection

- head and neck

- metastasis to cervical lymph nodes

- excision

- tumor excision

- carotid bifurcation