-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Peter Tilleard, Kate Swift, Daniel Tani, Ju Yong Cheong, Complex perianal abscess: a case report of shooting from the hip, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2025, Issue 1, January 2025, rjae801, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjae801

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

The perianal abscess is a common emergency surgical presentation. While in most cases simple drainage suffices, occasionally the abscess can track deeply presenting a management challenge. We describe the case of a complex circumferential horseshoe ischioanal abscess with extension below the levator ani through the greater sciatic notch and into the left gluteal region, with the collection involving the intergluteal space and gluteus maximus. The complex nature of the abscess warranted a novel joint approach by Colorectal surgery and Orthopaedic surgery teams. This case highlights the importance of maintaining a high degree of suspicion for, early recognition and imaging of deeper anorectal abscess extension.

Introduction

Anorectal abscesses, including perianal, ischioanal (ischiorectal) and supralevator abscesses, are common emergency surgical presentations. The cryptoglandular theory contends that most anal sepsis is secondary to the blocking, stasis and subsequent infection of the anal glands and their ducts [1, 2]. The suppurative process tracks along the planes of least resistance resulting in the range of possible anorectal abscess locations [2].

Due to their perceived simplicity anorectal abscesses are often managed without imaging and by junior surgical staff [3, 4]. However, deeper extension of the suppurative process requires experienced surgical input as demonstrated in this case.

Case report

A 62-year-old male presented to a regional hospital with a painful, erythematous and indurated left buttock. The patient was found to be tachycardic and febrile, with raised inflammatory markers. He was transferred to a regional tertiary surgical centre where he underwent emergent incision and drainage of a suspected perianal abscess. No imaging was performed. The patient was discharged the following day with oral antibiotics.

His past medical history included polymyalgia rheumatica (PMR) (taking prednisone 25 mg/day), type two diabetes mellitus (T2DM), obesity, ischaemic heart disease, and congestive cardiac failure. He had sacroiliac joint (SIJ) screws in situ following a quadbike injury. He had no personal or family history of colorectal cancer or inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).

On postoperative Day 3 he had a resurgence of his pain prompting readmission and an examination under anaesthesia. This found a more extensive ischioanal abscess with anterior and posterior communication forming a circumferential horseshoe abscess. A modified Hanley’s procedure was performed with bilateral posterior incisions for drainage and insertion of penrose drains.

Despite repeat surgical debridement the patient failed to improve. He was managed in the intensive care unit due to septic shock and required a short period of vasopressor support. Pelvic computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a contiguous abscess extending from the surgical cavity through the greater sciatic notch and into the left gluteal region (Figs. 1 and 2). This extended toward the hip and abutted his sacral metalwork.

CT pelvis (axial slices) demonstrating the perianal surgical site with packing, and the gas and fluid containing intergluteal collection.

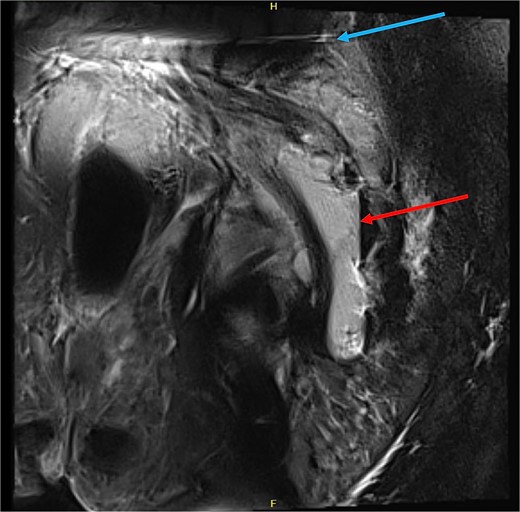

MRI pelvis (sagittal slice, patient lying lateral) demonstrating air-fluid level within the intermuscular abscess (red arrow), and artefact from SIJ screws (blue arrow).

A novel combined colorectal and orthopaedic surgery team approach was undertaken to drain the infection. The orthopaedic team drained the intergluteal abscess extension via a posterior approach to the hip (Moore/Southern approach) (Fig. 3). This discovered a large pocket of intramuscular pus within the gluteus maximus which tracked from the greater sciatic notch and a smaller pocket of pus adjacent to the short external rotator muscle group. The patient was moved into the lithotomy position and further debridement of the ischioanal fossae (ischiorectal fossae) up to the levator ani was performed by the colorectal surgery team. Vacuum-assisted closure (VAC) dressings were placed on the wounds and a diverting colostomy was performed. The patient subsequently required further washouts and his sacroiliac joint screws were removed due to their proximity to the abscess.

Clinical photographs of the patient’s VAC dressings (left) and the posterior approach to the hip with the exposed sciatic nerve (right).

He has been reviewed post discharge in the outpatient clinic and at four months post his initial presentation his wounds were fully healed. He is planned for a flexible sigmoidoscopy and subsequent reversal of his colostomy.

Discussion

An anorectal abscess is a common surgical emergency requiring prompt drainage. The extent and distribution of the abscess makes this case unique.

Our patient’s abscess had ascended from the perianal space and ischioanal fossae through the greater sciatic notch to involve buttock musculature. This deeper inter-gluteal abscess could not be accessed through the standard perianal approach. A literature review only revealed one other documented case in which a combined Colorectal and Orthopaedic approach had been taken for the management of an anorectal abscess [5]. In that case, described by Odak et al. [5], a 58 year old male was found to have septic arthritis of his left hip as a result of extension of an anorectal abscess. The combined approach of the Colorectal and Orthopaedic surgery teams in this case achieved effective drainage.

In this case the superficial suppurative process spread to the deep postanal space, resulting in a horseshoe ischioanal abscess. The fibromuscular anococcygeal ligament separates the left and right ischioanal fossae posterior to the anal canal [6]. The lack of a superior continuation of the anococcygeal ligament allows the abscess to ‘horseshoe’ around the anal canal posteriorly [7].

A modified Hanley procedure with division of the anococcygeal ligament was used to drain the horseshoe ischioanal abscess as it allows both posterior and bilateral drainage [2]. Hanley first described his approach to deep post-anal space sepsis in 1965. This involved primary fistulotomy in the midline with an incision extending to the tip of the coccyx [8]. In this method the subcutaneous external sphincter muscle, lower internal sphincter muscle and anococcygeal ligament are divided, in addition bilateral para-anal incisions into the abscess cavity are made [8]. The modified Hanley procedure preserves the sphincters and fistulas are managed with a seton and second stage procedure [7, 9].

In this case a colostomy was fashioned for faecal diversion. This is an accepted approach in severe anorectal sepsis and fistula disease in a range of settings, however the literature is sparse regarding indications and timing in the non-IBD, acutely septic adult patient [10–13]. The decision for diversion was made with the patient after imaging showed extension of the abscess into the gluteal region.

The American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons’ Practice Parameters for the Management of Perianal Abscess and Fistula-in-Ano notes that ‘Although anorectal abscess and fistula-in-ano are most commonly diagnosed and managed on the basis of clinical findings alone, adjunctive radiological studies can occasionally provide valuable information in complex tracts or recurrent disease.’ [4] This case highlights that a patient failing to improve after adequate drainage should have prompt senior review and consideration of imaging. When considering the need for imaging thought must also be given to patients’ risk of progressive infection; this patient’s risk was increased by his T2DM and steroids for PMR.

While perianal abscesses are often managed successfully by junior staff, it is important that deep abscesses are recognized and managed with senior input given the complexity of pelvic anatomy. Further this case demonstrates the importance of imaging and multidisciplinary approaches to difficult cases.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Funding

None declared.

References