-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Jay Lodhia, Atiyya Hussein, Alex Mremi, Constricting colonic lipoma causing acute intestinal obstruction, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2025, Issue 1, January 2025, rjae798, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjae798

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Colon lipomas are rare benign, nonepithelial tumors that are often asymptomatic. However, when symptoms do occur, they vary depending on the size and location of the lipoma and are generally nonspecific. Diagnosis is confirmed through histopathological analysis. Lipomas smaller than 2.5 cm can typically be observed without intervention, but larger or symptomatic lipomas require resection, which can be performed endoscopically or surgically. This case presents a rare phenomenon of synchronous left colonic lipoma leading to intestinal obstruction. Despite their benign nature, colonic lipomas can sometimes mimic malignant lesions, making histopathological analysis crucial for confirming the diagnosis.

Introduction

Lipoma of the gastrointestinal tract is a rare condition, first described by Baurer in 1757 [1]. Since 1955, it has been identified in only 0.2%–4.4% of large autopsy series. Colonic lipomas primarily affect females, usually during their fifth and sixth decades of life. They are most commonly found in the right colon, with 19% in the cecum, 38% in the ascending colon, 22% in the transverse colon, 13% in the descending colon, and 8% in the sigmoid colon. About 90% of these lipomas originate in the submucosa, occasionally extending into the muscularis propria, while 10% extend into the subserosa [1].

Gastrointestinal lipomas can vary greatly in size, ranging from 2 mm to as large as 30 cm. While most of these lipomas are asymptomatic, around 25% of cases may present with symptoms. These include abdominal pain, ranging from mild discomfort to severe cramping, along with recurrent episodes of constipation, nausea, and vomiting. Symptom severity is generally related to the lipoma's size [1, 2]. In this case report, we present a case of intestinal obstruction in a middle-aged female, caused by a synchronous colonic lipoma. The condition was managed surgically, with a favorable outcome.

Case presentation

A 54-year-old female presented with a 1-month history of recurrent unspecific abdominal pain that worsens with oral intake. She reported to experience normal bowel habits. Her medical history was notable for a cesarean section performed 10 years ago. She was clinically stable on examination with all systems unremarkable. Her complete blood count, biochemistry, plain abdominal-pelvic ultrasonography, and X-rays were unremarkable including urine dipstick. Stool test was also negative for Helicobacter pylori antigen; hence, she was discharged with oral proton pump inhibitors and antispasmodics, with a plan for outpatient colonoscopy and a contrasted abdominal-pelvic CT scan.

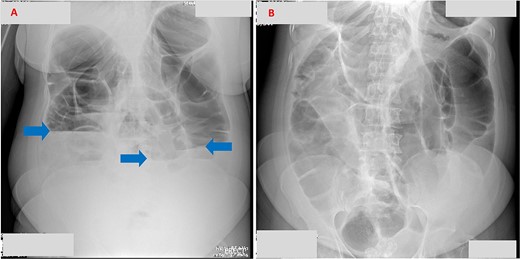

A week later, she presented to the emergency department with signs of complete intestinal obstruction. Blood tests showed a leukocyte count of 5.27 × 109/l, hemoglobin of 13.5 g/dl, and platelets of 329 × 109/L. Serum creatinine, sodium, and potassium were within normal ranges. An abdominal X-ray revealed dilated large bowel loops with multiple short air–fluid levels, consistent with large bowel obstruction (Fig. 1).

(A) Erect abdominal X-ray demonstrating multiple air–fluid levels (arrows). (B) Supine abdominal X-ray showing dilated bowel loops, suggestive of intestinal obstruction.

She was kept nil by mouth, with a nasogastric tube for decompression and IV fluids, and underwent emergency laparotomy after informed consent. Intraoperatively, two obstructive masses were identified in the splenic flexure and descending colon, along with a stricture in the mid-transverse colon. A subtotal colectomy with ileo-sigmoid anastomosis was performed, and the resected specimen was sent for histology. The liver, stomach, and mesentery were grossly normal, with no ascites.

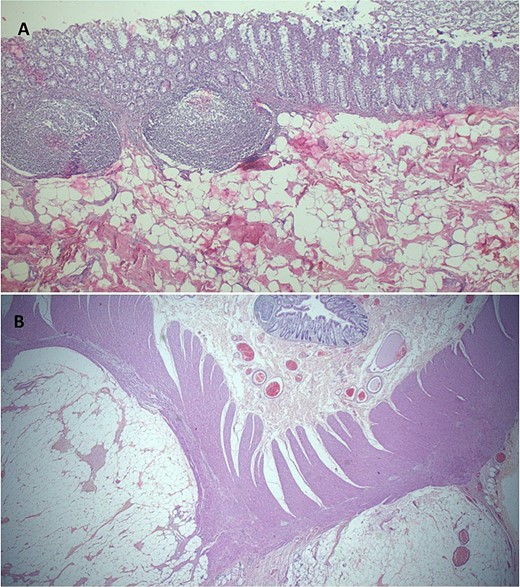

Her postoperative recovery was uneventful, and she was discharged on Day 6. At her 4-week follow-up, no complications were noted. Histology revealed a lipomatous tumor located 10 cm from the distal resection margin, encroaching the muscularis propria without evidence of cytological atypia (Fig. 2).

(A) Histopathology demonstrating normal colonic mucosa, submucosa demonstrates a mesenchymal lesion comprised of matured fat cells (H&E staining at 40× original magnification). (B) Photomicroscopy highlighting a benign, well circumscribed colonic lipomatous tumor dissecting muscularis propria muscles (H&E staining at 20× original magnification).

Discussion

In this case report, we present an unusual presentation of a colonic lipoma, characterized by its synchronous nature affecting the left colon, which contrasts with the typical right-sided predominance described in the literature. This lesion led to acute intestinal obstruction in a middle-aged female who had previously experienced vague symptoms. The case highlights the diverse presentations of what is usually considered a simple benign tumor of the GI tract, demonstrating its potential to mimic malignancy. Despite the use of advanced radiological imaging, the diagnosis of colonic lipomas can be challenging, often requiring histological analysis for confirmation. This case underscores the importance of maintaining a broad differential diagnosis, as clinical presentations can deviate from established paradigms.

Lipomas are nonepithelial benign tumors composed of adipose tissue, commonly found throughout the gastrointestinal tract, with the colon being the most frequent site. In the pediatric population, they classically present with symptoms such as abdominal pain, a palpable abdominal mass, and hematochezia. However, in adults, the clinical presentation is more variable, making preoperative diagnosis challenging despite advancements in radiological imaging techniques [3]. In adults, they can present as volvulus, intussusception, appendicitis, and even rectal prolapse as reported by Asghar et al. [4].

Colonoscopy can reveal characteristic signs of colonic lipomas, such as the “pillow sign,” a soft lesion with mucosal indentation resembling a pillow when pressed with closed biopsy forceps, and the “naked fat sign,” where fat extrudes after biopsy. These lipomas typically present as sessile or pedunculated submucosal lesions. In cases of ambiguous endoscopic findings, a biopsy may be necessary to confirm the diagnosis [2].

Microscopically, colonic lipomas consist of well-differentiated adipocytes organized into lobules. Among imaging modalities, an abdominal CT scan is the most sensitive diagnostic tool, typically showing fatty densitometric values of −40 to −120 Hounsfield units (HUs) with a smooth border and uniform appearance [5]. However, magnetic resonance imaging is less effective due to motion artifacts caused by peristalsis [6]. Several theories have been proposed regarding the development of GI lipomas. One theory suggests that defects in the development of lymphovascular circulation lead to localized overgrowth of adipose tissue, resulting in the formation of tumor-like masses. Another theory posits that chronic inflammation and irritation may play a role in their development [7].

Treatment is indicated when these gastrointestinal lipomas become symptomatic, especially in emergency settings, as the case presented [6]. Smaller lipomas which are less than 2.5 cm and those that are asymptomatic can be followed up. Those larger than that are recommended to be excised, endoscopically or surgical resection. Risks of endoscopic resection of larger lipomas include hemorrhage or perforation. And if left untreated, they are at risk of malignant transformation. Recurrence after resection is rare [8–10]. Although there is extensive literature discussing colonic lipomas and their treatment options, clear and standardized treatment guidelines remain elusive.

Colonic lipomas are rare, benign gastrointestinal lesions that often present asymptomatically but can cause significant complications like intestinal obstruction when large. Symptoms are typically nonspecific, making diagnosis challenging. This case underscores the importance of considering colonic lipomas and other benign lesions in the differential diagnosis of intestinal obstruction, as they can mimic more serious conditions such as malignancies. Given the absence of standardized management guidelines, treatment should be tailored to the patient’s presentation and local expertise.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the patient for permission to share her medical information to be used for educational purposes and publication.

Author contributions

J.L. conceptualized and drafted the manuscript. A.H. reviewed medical records and A.M. analyzed and reported histopathology slides and edited the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final script.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Funding

None declared.

References