-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Miguel A Moyon, Tatiana B Fernandez, Carlos Julio Lopez, Luis F Flores, Jose A Rosales, William Aguayo, Christian Rojas, Gabriel A Molina, Acute necrotizing pancreatitis caused by ampullary cancer: a case report, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2024, Issue 9, September 2024, rjae575, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjae575

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Ampullary malignancies are extremely rare tumors that are usually diagnosed when they cause biliary obstruction. Rarely, any tumor or mass near or within the pancreas can cause acute pancreatitis and on even rarer occasions, these tumors can cause severe complications such as acute peripancreatic fluid collections, necrotizing pancreatitis, and infections. As a medical team, we must embrace these difficulties and these dreadful scenarios, as they are opportunities for growth for the medical team and opportunities to save even more patients. We present the case of a 59-year-old male who suddenly presented acute severe pancreatitis with necrosis and infection due to an ampullary mass. After recovery, he was referred to a tertiary center, where his cancer was successfully treated.

Introduction

Ampullary malignancies are extremely rare tumors (0.2%) of the gastrointestinal tract [1]. They usually appear with symptoms of biliary obstruction, including jaundice, nausea, and abdominal pain [1, 2]. Treatment often involves resection or chemoradiation [2]. We present the case of a 59-year-old male with severe necrotizing infected pancreatitis caused by an intestinal ampullary carcinoma. To our knowledge and after a comprehensive literature search, it is the first case ever reported.

This work has been reported in line with the SCARE criteria.

Case report

The patient is a 59-year-old male with a past medical history of hypothyroidism, type 2 diabetes, and dyslipidemia. Suddenly, he presented with acute upper abdominal pain. At first, the pain was mild and colicky; however, as time passed, the pain became constant and severe and was accompanied by nausea and vomits. Therefore, he was brought immediately to the emergency room by his family. He did not disclose any weight loss, jaundice, or any other symptoms. On clinical examination, a tachycardic (103 beats per min), tachypneic (22 beats per min), and febrile (38.2°C) patient was encountered. He had severe pain in his upper abdomen with tenderness.

Initial blood workup showed leukocytosis (11 400/mm3) without neutrophilia (48.5%), but his pancreatic enzymes were highly elevated; lipase levels were registered at 3755.7 U/L and amylase at 3218 U/L. Bilirubin and transaminase levels were within normal ranges, while gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT) was at 863 U/L. Blood gas analysis at that time reported a pH of 7.31, with lactic acid at 3.61. The PaO2/FiO2 ratio was 337, and creatinine was measured at 1.18 mg/dl.

Further evaluation, including abdominal ultrasound, ruled out the presence of gallstones but detected sludge. Also, the common bile duct (CBD) was dilated and measured 11 mm. Therefore, a magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography revealed a CBD of 12 mm without any apparent obstruction and a dilated Wirsung duct of 7.3 mm. The pancreas exhibited enlargement, and its surrounding fat showed early signs of inflammation and necrosis. Alterations at the ampullary level were also noted, suggesting an inflammatory or neoplastic etiology.

Severe acute pancreatitis was suspected based on the 2012 Atlanta Classification of acute pancreatitis, and the patient was admitted to the ICU and reanimated aggressively. The patient's Modified Marshall scoring system for organ failure 48 hours after admission was over ≥2 in respiratory, cardiovascular, and renal systems. Three days passed, and he continued to respond poorly to this treatment and persisted with tachypnea, tachycardia, and his oxygen requirement increased also his C-reactive protein level was 327.43 mg/dl.

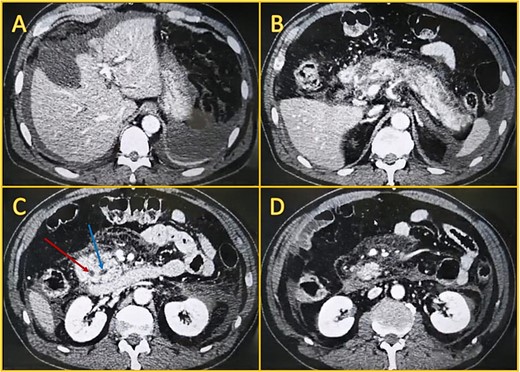

Local complications were suspected, and a contrast-enhanced abdominal computed tomography (CT) was done. It revealed a peripancreatic and perihepatic fluid. The pancreas was enlarged and had several areas of necrosis with gas bubbles (Fig. 1).

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography. A: Perihepatic fluid. B: The pancreatic head, body, and tail have non-enhancing areas compatible with necrosis. C: Dilated biliary duct (leftmost arrow) and Wirsung (rightmost arrow). D: Peripancreatic fluid.

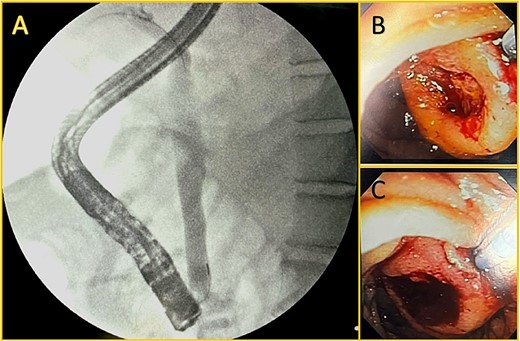

Broad-spectrum antibiotics were initiated (Piperacillin-tazobactam at first and later carbapenem due to the patient's clinical condition and culture results), and the patient responded well; nonetheless, his bilirubin and GGT levels rose over 12 mg/dl and 1234 U/L on his eleventh day in the ICU. Therefore, an endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) was performed. During the procedure, a mass with surface ulceration was identified on the ampulla, which was subsequently biopsied. A 10Fr biliary prosthesis was inserted, freeing the bile duct from that obstruction. (Fig. 2).

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. A: Cholangiography is shown, and successful cannulation of the biliary duct was achieved, with the identification of a dilated duct and no filling defect. B and C: An ampullary mass is shown with surface ulceration.

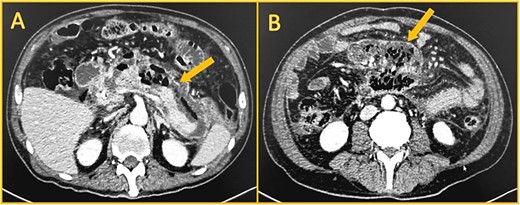

On the twentieth day, despite receiving carbapenem, the patient once again presented with a high fever. A subsequent computed tomography scan unveiled a capsulated peripancreatic collection measuring approximately 500 cc (Fig. 3). Using CT-guided percutaneous drainage, the collection was drained, and a pigtail was left in place. Nonetheless, the patient persisted with fever, was unable to eat, and suffered from hemodynamic instability. As the patient continued in a septic shock, and since endoscopic drainage was unfeasible due to our hospital limitations, the patient was scheduled for a laparoscopic necrosectomy. Intraoperatively, multiple dense adhesions were identified between the omentum, stomach, and anterior abdominal wall. The pancreas was meticulously debrided of necrotic tissue, and a drain was left. After surgery, the patient made a good recovery. The drain's amylase levels were negative for fistula. He had no fever or signs of shock. The drain had low and serous production, and he could eat solid foods without complications. On his thirtieth day, he was finally discharged and kept under close follow-up. Three months post-discharge, the patient was referred to the hepatobiliary center for definitive management of the ampulloma. He presented in good overall condition with adequate nutritional status. The procedure involved a pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy and a Roux-en-Y reconstruction. The procedure was uneventful, and the patient's condition improved, and he was discharged without complication.

Shows contrast-enhanced computed CT. A: Large collection (arrow) anterior to the pancreas, with gas. B: Walled-off necrosis (arrow) with gas.

Pathology reported a stage IIA G1, pT3a N0 M0, 3.3 × 1 × 1 cm well-differentiated intestinal ampullary carcinoma without lymph node invasion. Twelve lymph nodes were retrieved from the specimen, all free of tumor spread. Lymphovascular and perineural invasion were also absent, and all margins were negative.

On follow, the patient is under close control by Oncology and is receiving adjuvant chemotherapy with gemcitabine.

Discussion

Ampullary cancers are rare and account for only 0.2% of all gastrointestinal cancers [1, 2]. They can differ based on their epithelium of origin, intestinal, or pancreaticobiliary; this is important as ampullary adenocarcinomas with pancreaticobiliary histology have a much worse outcome than those with intestinal histology [2]. From an anatomical point of view, they arise from the ampulla of Vater, named after German anatomist Abraham Vater, who first described this mucosal papillary mound in 1720 [1–3]. This union between the central pancreatic duct and the distal common bile duct represents a critical point, as most patients will present with symptoms similar to those with extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma and pancreatic adenocarcinoma [3, 4].

Jaundice, diarrhea, steatorrhea, and gastrointestinal bleeding with melena are a frequent finding in these patients [1, 4, 5]. Due to this, they are usually investigated, and this malignancy is frequently diagnosed earlier than those with pancreatic cancer [1, 2].

Acute pancreatitis associated with metastatic disease of the pancreas, ampullary cancer, and biliary cancer is rare [6, 7]. Still, it is a well-recognized association, primarily due to the fact that 1% of all acute pancreatitis are due to cancer [2, 7]. Adenocarcinoma, ampullary cancers, and pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma have been identified as causes of acute pancreatitis; tumor growth, exploration, and inflammation can cause ductal obstruction, leading to severe pancreatitis [2, 6]. Nonetheless, the existing literature regarding these rare scenarios is limited [6]. We believe that in our case, as the tumor grew, it obstructed the bile and pancreatic duct, causing severe necrotizing pancreatitis.

Necrotizing pancreatitis represents a remarkable scenario of this disease because of its prolonged disease course, complex therapeutic, and extremely high risk of long-term complications [8]. Pancreatic necrosis occurs in between 10% and 20% of patients with acute pancreatitis and can occur from any etiology of acute pancreatitis, even cancer [8, 9]. In our patient, we recognized the mass during its early stages because the patient's condition was deteriorating rapidly.

Necrotizing pancreatitis is a severe condition with a mortality of up to 30% if signs of organ failure are present [9]. If infections arise in necrotizing pancreatitis, radiology, and endoscopic drainages should be preferred whenever possible to decrease the risk of percutaneous fistula and the high morbidity and mortality (95% and 25%, respectively) associated with surgery [9].

However, in our case, as the collections were infected and the patient's condition deteriorated even with ERCP, surgery was necessary. The risk of death from infected necrotizing pancreatitis outweighed the risk of complications and ampullary cancer. After our surgery, the patient had a satisfactory recovery that opened the way to a cancer-free life. This unfortunate and possibly fatal event for him had a silver lining: the early diagnosis of his cancer and being able to act in time.

Radical surgical resection with lymphadenectomy represents the only curative treatment and is possible in approximately 50% of all patients due to the high rate of lymph node involvement. [1, 3] Multiple studies now suggest a potential survival benefit from the administration of adjuvant chemotherapy, with less support for the use of radiation [1].

In our case, the patient is on close follow-ups after surgery and in good condition one year after surgery.

In conclusion, the complications of acute pancreatitis are threatening, not only because of their complexity but also because they tend to be overwhelming for the healthcare system, the patient, and the medical team. Among the most frightening of them is the infected pancreatic necrosis, which by itself is a severe complication. When an ampullary cancer causes this complication, the scenario can be even more challenging to treat.

At a time like this, only an accurate diagnosis accompanied by an adequate medical team can determine the life and death of a patient.

Even if such a terrible complication as infected pancreatic necrosis appears, it should not be the end but a new opportunity; in our case, it meant having the possibility of living cancer-free.

As a medical team, we must embrace these difficulties as they are opportunities for growth for the medical team and learning opportunities.

Conflict of interest statement

We declare no conflict of interest.

Funding

We have no funding.

Data availability

The data and the informed consent will be available to the Editor on request.

Ethical committee approval

We have approval from the ethics committee.

Informed consent

We have written consent from the patient and is available on request by the Editor.