-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Rahel Abebayehu Assefa, Henok T/Silassie Zeleke, Azmera Gissila Aboye, Triple case report of persistent sciatic artery in Ethiopia: a rare vascular anomaly, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2024, Issue 8, August 2024, rjae474, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjae474

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Persistent sciatic artery (PSA) is a rare congenital vascular anomaly resulting from embryologic axial artery malformation in the lower limb. This case report presents three patients aged 45–60, each with bilateral PSA presenting with symptoms indicative of PSA complications, including aneurysmal degeneration, limb ischemia, thromboembolism, or neuralgia from nerve compression. It highlights the diagnostic process, management strategies, and clinical outcomes observed at a tertiary referral hospital. Treatment involved a collaborative, multidisciplinary approach with vascular surgeons, internists, and radiologists tailoring interventions to individual patient findings and disease progression. This report aims to provide insights into the diverse presentations and management of PSA in a resource limited setting, encouraging further reporting and case studies to enhance understanding of therapeutic outcomes.

Introduction

Persistent sciatic artery (PSA) is a rare congenital vascular anomaly resulting from malformation of the embryologic axial artery of the lower limb (LL) [1]. It persists as the primary arterial supply with concurrent aplasia or hypoplasia of the femoral artery [1, 2]. Its estimated incidence is 0.025–0.04%, with fewer than 200 reported cases and a bilateral presentation in 25–30% of cases [2–4]. PSA is prone to early atherosclerosis and distal embolization [4, 5]. Symptomatic patients typically present with aneurysmal degeneration, or less frequently with limb ischemia secondary to thromboembolism, or neuralgia from sciatic nerve compression [4–8]. Computed tomography angiography (CTA) effectively detects PSA, even in cases with complete occlusion and enables evaluation for complications [2, 9]. Treatment options for symptomatic PSAs include open surgery or endovascular treatment (EVT) [1, 4, 6, 7].

Case 1

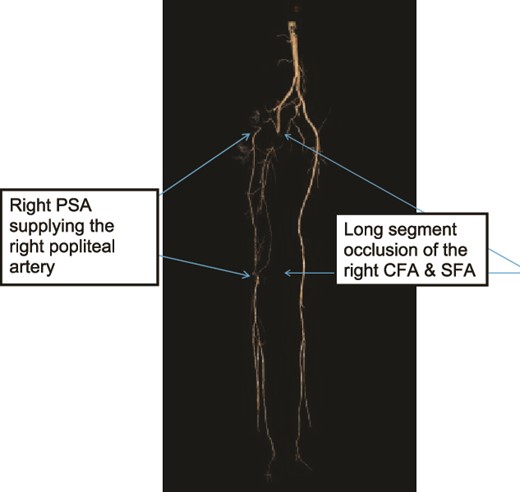

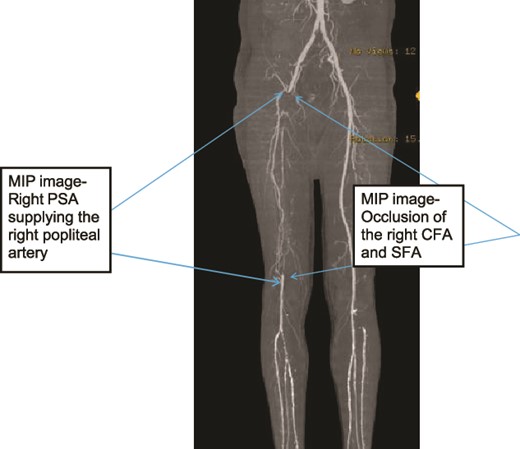

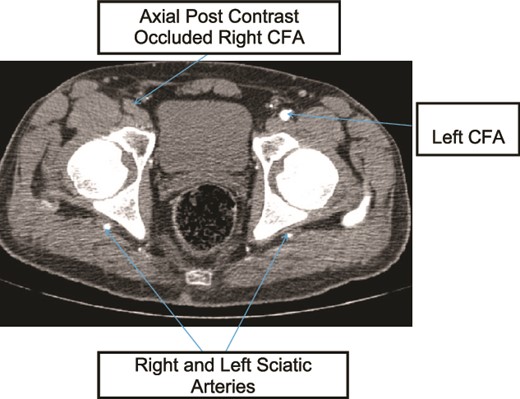

A 45-year old known diabetic and hypertensive male patient presented with right foot pain of one year. He had right calf claudication for 4 years and associated darkening of the right little toe of 1 month. He was a cigarette smoker for 15 years, but had discontinued 1 month prior. On examination, he had right fifth digit dry gangrene with non-palpable pulses in the right popliteal artery (PA), dorsalis pedis artery (DPA), or posterior tibilias artery (PTA). Preoperative ABI was not recordable (no flow detected in DPA or PTA with handheld Doppler ultrasound). Doppler ultrasound showed ~90% occlusion of right common femoral artery (CFA) with hemodynamically significant downstream insufficiency and scattered foci of arterial wall calcification and wall thickening of bilateral LL arteries. CTA showed mild atherosclerotic disease, long segment right CFA, superficial femoral artery (SFA), proximal profunda femoris (PF), proximal and mid right PA occlusion and right PSA supplying collateral to the distal PA with right tibio-peroneal trunk atherosclerotic occlusion (Figs 1–3). Patient underwent right CFA thrombectomy and femoro-popliteal (supragenicular) bypass using ipsilateral subcutaneously tunneled reversed great saphenous vein (GSV). Postoperative ABI was 1.2 and he was discharged on Per Os (PO) anticoagulant (Rivaroxaban). On a 3-year postop follow up, patient had mild claudication with no rest pain or wounds.

Case 1—3D-subtraction image of LL CTA oblique view of the bilateral LL arteries showing long segment occlusion of the right CFA and right SFA and right PSA.

Case 1—3D-Maximum Intensity Projection image of LL CTA frontal view of the bilateral LL arteries showing long segment occlusion of the right CFA and right SFA; right PSA supplying the right popliteal artery.

Case 1—axial image of LL CTA of the bilateral LL arteries at the level of the femoral head showing occlusion of the right CFA and bilateral PSA with larger caliber right PSA.

Case 2

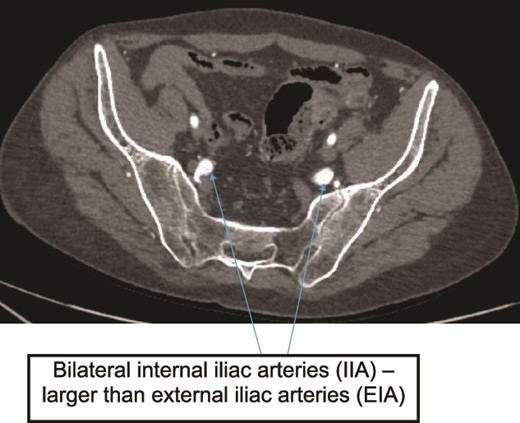

A 47-year old male patient presented with right thigh and leg pain of 1 year with associated decreased muscle mass and right gluteal area swelling with pain which radiated to his posterior thigh for 6 months. Pain was exacerbated by lying or sitting. He was a smoker for the past 15 years but discontinued 2 months prior. On examination, the right LL muscles were atrophic with gross discrepancy in muscle mass. He had a 4 × 3 cm2 pulsatile palpable, slightly tender mass over the outer upper quadrant of the right gluteal region. He had non-palpable pulses in the right PA, DPA, or PTA. Power was 4/5 in the right LL with intact sensory function. Preoperative ABI was not recordable. CTA showed bilateral PSA with right gluteal sciatic artery thrombosed aneurysm and distal occlusion (Figs 4–6) After delay due to patient acquiring COVID, he was subsequently operated and underwent right PSA ligation and aneurysm hematoma evacuation in prone position through posterolateral buttock curvilinear incision approach without aneurysm wall excision. The patient then underwent CFA- to PTA-reversed GSV bypass after repositioning. Postoperatively ABI on the first post op day was 0.8. The patient was unable to afford PO anticoagulant and was discharged with antiplatelet (low-dose aspirin), which the patient discontinued after 1 month. On the 2-month postoperative follow-up, the patient had recurrence of burning sensation over the right leg with absent distal pulses but disappeared from follow-up thereafter.

Case 2—axial image of LL CTA of pelvic cavity showing the IIAs larger size compared to the external iliac arteries.

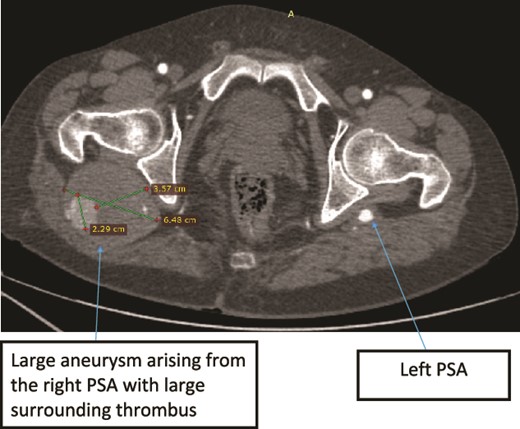

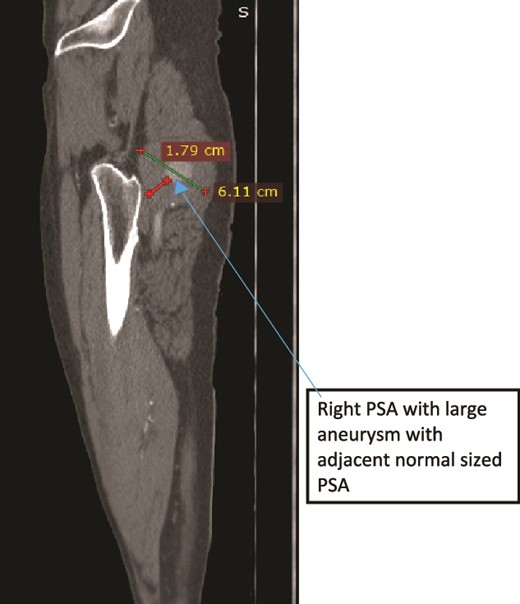

Case 2—axial images of LL CTA of the bilateral LL arteries at the level of the femoral head showing large bilateral PSAs and a large aneurysm with surrounding thrombus of the right PSA.

Case 2—sagittal images of LL CTA of the right LL arteries showing large aneurysm with surrounding thrombus with adjacent normal-sized PSA.

Case 3

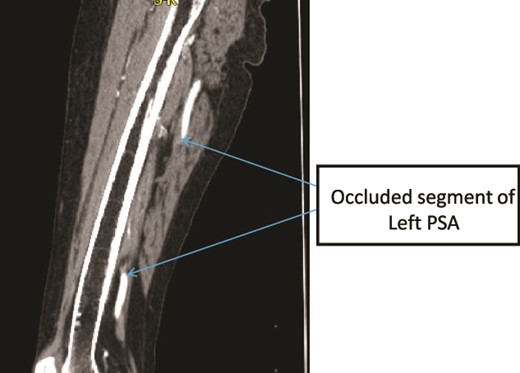

A 60-year old known psychiatric female patient presented with left LL pain and swelling for 1 week. She had claudication for 1 year and 4 months prior to presentation, she had fifth toe amputation after developing ulceration. On examination, all distal pulses were absent in the affected limb which was cold, with tender calf muscles and absent motor and sensory function. Patient was not cooperative for gluteal area examination. CTA showed bilateral prominent internal iliac arteries (IIAs), bilateral PSAs with left PSA fusiform aneurysm with surrounding thrombus, and no signs of rupture (Fig. 7) There was also central filling defect occluding the left mid-thigh PSA and left PA (Figs 8 and 9) With a diagnosis of Class III acute limb ischemia, the patient was offered surgical amputation but refused and was discharged against medical advice.

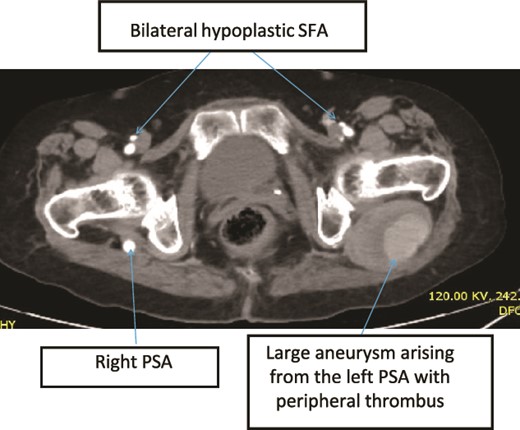

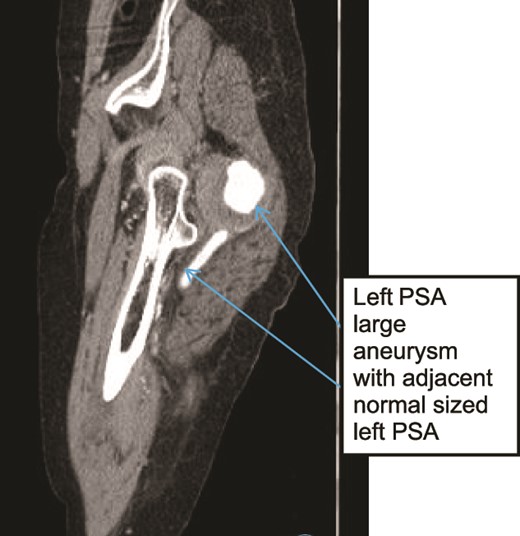

Case 3—axial images of LL CTA of the bilateral LL arteries at the level of the CFA bifurcation showing large bilateral PSA and small bilateral SFA; large aneurysm with surrounding thrombus at the left PSA.

Case 3—sagittal images of LL CTA of the left LL arteries showing large aneurysm with surrounding thrombus with adjacent patent normal sized upper left PSA.

Case 3—sagittal images of LL CTA of the left LL arteries showing occluded left PSA in the mid-thigh.

Discussion

In low- and middle-income countries such as Ethiopia, EVT options, such as embolization with coiling or plug, or covered stent graft insertion [1], are not available. Therefore, management is solely surgical, which is typically reserved for symptomatic limbs only [1, 2]. It is not clear from the literature review if treatment or follow-up is required for asymptomatic PSA, but majority generally recommend monitoring [1, 2, 7, 10].

In cases with aneurysmal degeneration, such as in the second patient, preventing rupture and distal embolization requires excluding flow into the aneurysm [7, 10, 11]. Surgical ligation, whether trans- or retro-peritoneal or transgluteal, is necessary, proximally depending on aneurysm neck location. Distal ligation of the sciatic or PA should also be achieved [3, 11]. In the second case, a posterolateral buttock curvilinear incision approach successfully achieved both proximal and distal sciatic artery ligation without complications or need for aneurysm wall excision [7], offering a feasible alternative.

Symptomatic patients with incomplete SFA require bypass surgery to restore distal blood flow in addition to aneurysm treatment [10]. Options include femoropopliteal bypass (typically CFA-to-PA bypass) or iliopopliteal transobturator bypass [7, 11, 12]. Bypass surgery was performed for both male patients in this case report. In cases where CFA is diseased or hypoplastic, sciatic aneurysmorrhaphy with interposition graft placement can be considered to restore distal flow, though it is a less favorable option [11, 12].

Unfortunately, if patients are misdiagnosed, and present late or fail to receive timely intervention, amputation of the limb is inevitable, and may be necessary even after intervention [2, 7].

Conclusion

Multidisciplinary approach to the classification and management of PSA, including vascular surgeons and radiologists is key for the positive outcome of treatment. The goal is to alleviate symptoms, restore proper blood flow, and prevent further complications.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Funding

None declared.