-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Yukihiro Tatekawa, Yukihiro Tsuzuki, Kiyotetsu Oshiro, Yoshimitsu Fukuzato, Surgical technique for epigastric incisional hernia after omphalocele repair: bilateral modified composite flaps using the upper rectus abdominis muscle and the vertically inverted flap of the lower rectus abdominis fascia, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2024, Issue 4, April 2024, rjae259, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjae259

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

We present a patient who developed an incisional hernia, from epigastrium to umbilicus, after omphalocele repair. The hernia gradually enlarged to a 10 cm × 10 cm defect with significant rectus abdominis muscle diastasis at the costal arch attachment point. At 6 years of age, the abdominal wall defect in the umbilical region was closed using the components separation technique. For the muscle defect of the epigastric region, composite flaps were made by suturing together the flap of the upper rectus abdominis muscle, after peeling it away from the costal arch attachment point, and the vertically inverted flap of the lower rectus abdominis fascia, created with a U-shaped incision. The composite flaps from each side were reversed in the midline to bring them closer and then sutured; the abdominal wall and skin were then closed. Five months after surgery, the patient had no recurrent incisional hernia and no wound complications.

Introduction

Single-stage surgical repair can be performed for small omphaloceles; for large or ruptured omphaloceles, other techniques are necessary [1]. The components separation technique (CST) has been performed for infants with giant omphaloceles [2–5]. If primary closure by CST is impossible, separation of the posterior rectal sheath from the rectus abdominis muscle can increase the distance the flap can travel; this is called the modified CST [6, 7].

We encountered a patient who had an incisional hernia from the epigastrium to the umbilicus after omphalocele repair. This patient also had an incisional hernia in the epigastrium that had developed a significant rectus abdominis muscle diastasis at the costal arch attachment point. We used novel surgical innovations to close the abdominal wall defect.

Case report

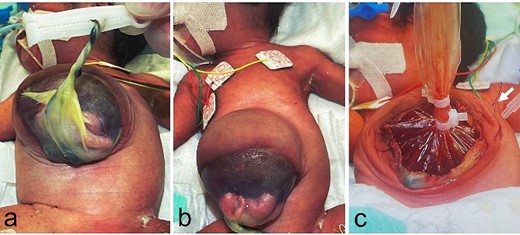

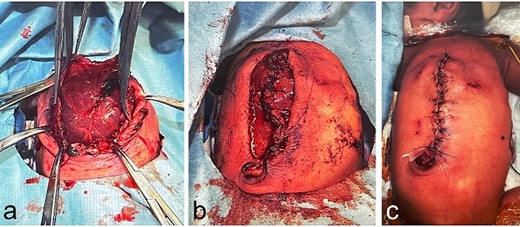

A female infant was born at 36 weeks of gestation, weighing 1462 g. At birth, she was diagnosed with an omphalocele with prolapse of one-third of the liver and part of the small intestine. In addition, a ring-shaped portion of the rectus abdominis muscle was missing (Fig. 1a and b). She underwent staged surgical repair on day of Life 2. A wound retractor was used as a ‘silo’ to stretch the abdominal wall muscles and was fixed with sutures to the muscle layer and the skin in four places due to the ring-shaped defect in the rectus abdominis muscle (Fig. 1c). On day of Life 6, the patient underwent the second stage of the repair, when subcutaneous tissues were mistaken for the muscle layer and were sutured together, and then the skin was closed (Fig. 2a–c).

Physical findings at birth and at the primary surgery, day of Life 2; (a, b) prolapse of one-third of the liver and part of the small intestine is recognized in the omphalocele, and there is a ring-shaped defect in the rectus abdominis muscle; (c) the wound retractor is sutured to the muscle layer and the skin in four places (white arrow: suture).

Operative findings at the second surgery, day of Life 6; (a–c) the subcutaneous tissues are sutured and the skin is closed.

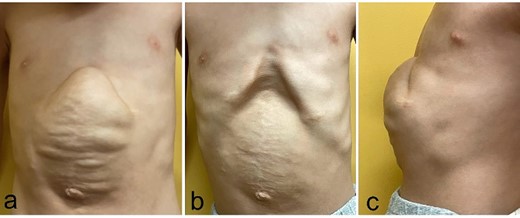

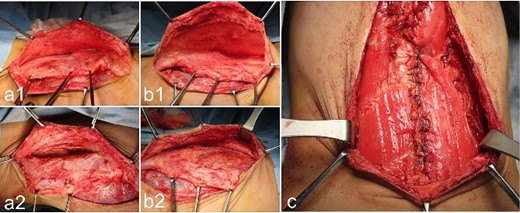

An abdominal incisional hernia appeared early after surgery and gradually enlarged to a 10 cm × 10 cm defect with a significant rectus abdominis muscle diastasis at the costal arch attachment point (Fig. 3a–c). At 6 years of age, when the patient weighed 14.1 kg and was 104.3 cm tall, closure of the abdominal wall defect was scheduled. The plan was to use CST to close the abdominal wall defect in the umbilical region (Fig. 4); however, the muscle defect of the epigastric region could not be closed using this technique. Instead, composite flaps were created by suturing together the flap of the upper rectus abdominis muscle, which had been peeled away from the costal arch attachment point, and the vertically inverted flap of the lower rectus abdominis fascia, created using a U-shaped incision. The composite flaps on each side were reversed in the midline and sutured together (Fig. 5). The abdominal wall and skin were then closed. Five months after surgery, there was no recurrence of the incisional hernia and no wound complications (Fig. 6).

Physical findings before the third surgery, 6 years of age; (a–c) an abdominal incisional hernia measures 10 cm × 10 cm with a significant rectus abdominis muscle diastasis at the costal arch attachment point (a: during inspiration; b: during expiration; c: lateral view during inspiration).

Operative findings at the third surgery: umbilical region; (a1, a2): the right external oblique muscle is cut vertically from the lower edge of the costal arch to the umbilicus at the lateral edge of the rectus abdominis muscle; (b1, b2) the left external oblique muscle is cut vertically, from the lower edge of the costal arch to the umbilicus at the lateral edge of the rectus abdominis muscle; (c) the rectus abdominis muscle is mobilized medially on both sides, and the medial edges are sutured together after making a U-shaped incision in the lower rectus abdominis fascia.

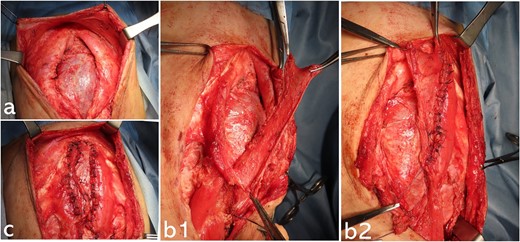

Operative findings at the third surgery: epigastric region; (a) there is a significant rectus abdominis muscle diastasis at the costal arch attachment point; part of the liver surface is covered with connective tissue; (b1, b2) the upper rectus abdominis muscle is peeled away from the costal arch attachment; the anterior aspect of the lower rectus abdominis sheath is cut using a U-shaped incision to be the same length as the epigastric defect; the fascia with the U-shaped incision is vertically inverted; the composite flap is made by suturing together the flap of the upper rectus muscle and the vertically inverted flap of the lower rectus fascia (b1: before suturing the composite flap on the right side; b2: after suturing the composite flap); (c) both composite flaps are reversed in the midline and sutured together, covering the epigastric muscular defect.

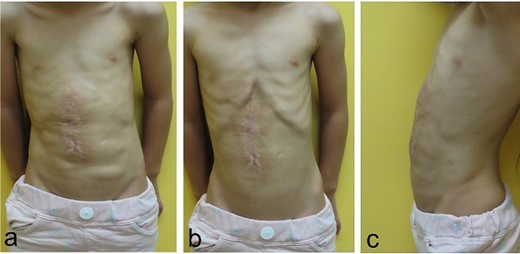

Physical findings on 5 months after the third surgery; (a–c) an abdominal incisional hernia develops no recurrent incisional hernia and no wound complications (a: during inspiration; b: during expiration; c: lateral view during inspiration).

Discussion

The CST was first described by Ramirez and colleagues in 1990 [2]; it is a useful technique to repair large abdominal wall defects [3, 4]. The use of CST for an infant with a giant omphalocele was first described in 2005 [5], and van Eijck and colleagues reported 10 pediatric patients with giant omphaloceles who were treated with this technique in 2008 [8]. In this series, the median hernia diameter was 8 cm (range, 6–9 cm). If primary closure is impossible, separation of the posterior rectal sheath from the rectus abdominis muscle can increase the distance the flap can travel; this technique is called the modified CST [6, 7]. The bilateral anterior rectus abdominis muscle sheath turnover flap (RSTF) method involves cutting the anterior rectus sheath vertically at the lateral edge of the rectus abdominis muscle, then turning over the flap of the sheath to suture it to the similar flap on the other side [9]. Our patient had an incisional hernia from the epigastrium to the umbilicus after omphalocele repair; the portion of the hernia in the epigastrium had developed a significant rectus abdominis muscle diastasis at the costal arch attachment point. We used a modified CST and RSTF to close the abdominal wall defect in a manner focusing on autogenous tissue repair.

In this patient with an epigastric incisional hernia after omphalocele repair, the composite flaps, consisting of the flap of the upper rectus abdominis muscle (after peeling it away from the costal margin) and the vertically inverted flap of the lower rectus abdominis fascia, were reversed and sutured in the midline. This technique was useful for closing the epigastric muscular defect.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Funding

None declared.