-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Megan Bedard, Madison McInnis, Kaysie Banton, Spontaneous pneumoperitoneum presenting as an acute abdomen, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2024, Issue 2, February 2024, rjae049, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjae049

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Most cases of pneumoperitoneum with associated peritonitis are due to perforation of a hollow viscus. In cases where hollow viscus perforation is not the cause, the pneumoperitoneum is classified as spontaneous and typically can be further subcategorized into thoracic, abdominal, gynecologic, and idiopathic categories. Spontaneous pneumoperitoneum is classically seen in asymptomatic patients, however in a small number of cases patients can present with a concomitant peritonitis. This case report presents a patient that had signs of sepsis and peritonitis with moderate pneumoperitoneum on computed tomography (CT) imaging but was found to have no perforated hollow viscus after an extensive operative and non-operative work up.

Introduction

Pneumoperitoneum is defined as the presence of free air within the peritoneal cavity with 90% of cases being secondary to hollow viscus perforation [1]. The remainder of cases present without any evidence of intraperitoneal perforation and are collectively referred to as spontaneous or non-surgical pneumoperitoneum. Causes of spontaneous pneumoperitoneum typically fall into four categories: thoracic positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) ventilation, bronchopulmonary fistula, severe coughing, pneumomediastinum), abdominal (postoperative, pneumatosis cystoides intestinalis, peritoneal dialysis), gynecologic (vaginal insufflation, postpartum exercise, pelvic inflammatory disease, coitus), and idiopathic [2]. Most cases of spontaneous pneumoperitoneum are asymptomatic and discovered incidentally, but rarely patients can present with peritonitis [3]. This report highlights the case of a 30-year-old female who presented with severe abdominal pain and a large amount of pneumoperitoneum on CT without any identifiable cause after extensive workup including surgical intervention.

Case report

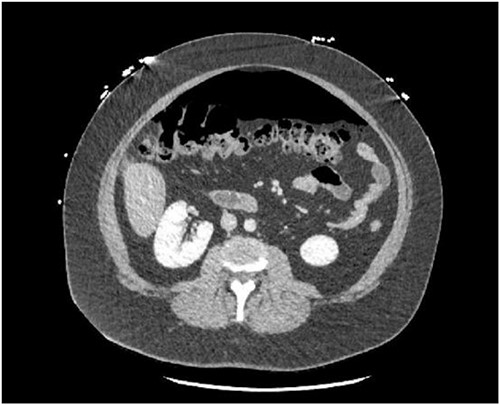

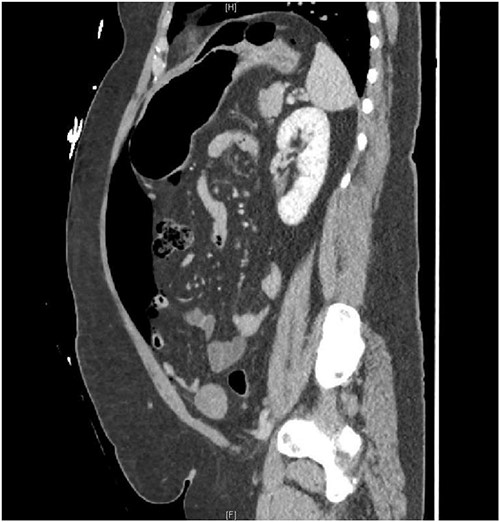

A 30-year-old female presented to the emergency department due to severe abdominal pain that had started suddenly 5 h prior to arrival. Symptoms began after eating dinner. She had no prior medical history or prior abdominal surgeries, however had recently been taking an increased amount of NSAIDs due to a tooth infection. On presentation, she was tachycardic with a heart rate in the 120 s and had a leukocytosis of 14.9. She was otherwise hemodynamically stable and afebrile. A CT abdomen/pelvis with IV (no oral) contrast demonstrated a moderate amount of pneumoperitoneum without a definite source (Figs 1 and 2). She was taken for exploratory laparotomy where full examination of the gastroesophogeal junction, stomach, duodenum, ascending and descending colon, and pelvic organs were examined in detail without any findings of perforated viscus. An intraoperative endoscopy was then performed and was normal, as well as intraoperative colonoscopy. A temporary abdominal closure device was placed, and she was taken to the intensive care unit (ICU) for continued monitoring. Post-operatively she underwent further testing including a CT abdomen/pelvis with IV and oral contrast followed by gastrografin enema both with negative findings. She returned to the operating room for abdominal closure on post-operative day 2 that required an anterior component separation with onlay mesh given significant loss of domain. At this time, her leukocytosis had also resolved. The patient was tolerating a regular diet 3 days after abdominal closure (5 days after index procedure) and discharged home on post-operative day 6.

Discussion

In the setting of an acute abdomen, the presence of pneumoperitoneum is most commonly indicative of perforated viscus while spontaneous pneumoperitoneum is more commonly associated with a benign abdomen. Approximately 10% of cases of pneumoperitoneum are associated with physiologic processes that do not necessarily require surgical management [4]. These etiologies can be thoracic, abdominal, gynecologic, or idiopathic. Rare cases have been reported to be caused by sexual activity [5], hot tub use [6], scuba diving [7], and cocaine use [8].

In this case, an underlying cause of the patient’s pneumoperitoneum was not identified despite extensive workup and remains idiopathic in nature. Idiopathic pneumoperitoneum is a rare phenomenon and should always remain a diagnosis of exclusion after a thorough workup has ruled out other causes. Given the small number of reported cases, there remains controversy on how best to treat these patients. Due to the ominous nature of pneumoperitoneum and high risk of complications if left untreated when secondary to perforated viscus, most patients will undergo laparotomy. Some studies recommend non-operative management in patients who are not septic or peritonitic [9]. Often in these patients, treatment will include intravenous antibiotics, total parenteral nutrition, bowel rest, serial examinations, and repeat imaging [10]. Some studies have even suggested that conservative management is indicated in patients with signs of peritonitis [11, 12]. As in all surgical patients, risks and benefits of surgical intervention must be weighed in each individual patient prior to making final operative versus non-operative management decisions. There is unfortunately not enough data at this juncture to create a reliable algorithm to determine which patients can avoid an operation, and therefore some number of negative laparotomies will be inevitable in the management of spontaneous pneumoperitoneum. Our patient presented with signs of sepsis and peritonitis and while no underlying cause could be identified in surgery, her operation was still warranted. We urge each physician to use clinical judgment with each patient and not to delay intervention in those with sepsis, peritonitis, or hemodynamic instability.

Author contributions

All authors were involved in the operation and treatment of this patient. M.B. and M.M. prepared the manuscript and literature search. K.B. gave the final approval of the version to be published. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Funding

None declared.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report. A copy of the written consent is available for review from the corresponding author of this manuscript upon request.