-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Dinithi Liyanage, Richard Clough, Deepa Pandit, Stuart McKirdy, A 20-year misdiagnosis: a rare presentation of a basal cell carcinoma, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2024, Issue 2, February 2024, rjae028, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjae028

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most common form of skin cancer. BCCs are seldom reported on the sole of the foot due to a lack of exposure to UV radiation which is the main risk factor. We present a brief literature review and case report of a 42-year-old female with a non-resolving lesion on the mid-arch of her left foot over a 20-year period. Tissue diagnosis identified the lesion as a BCC. Disease-free control was achieved but the patient experienced significant morbidity resulting in three separate procedures to diagnose, excise and reconstruct the defect. When evaluating lesions on the sole clinicians should consider BCC as a differential, particularly in those which do not respond to initial treatment.

Introduction

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most common form of skin cancer [1, 2]. They are characterized by slow growth and rare metastasis. If left untreated, BCCs can invade surrounding structures and soft tissues aggressively [1]. Early diagnosis plays a crucial role in reducing morbidity, enabling less aggressive surgery and complex reconstruction [1]. BCC on the sole of the foot accounts for <1% of all reported cases in the literature (Table 1) [3–13].

Case reports of BCC found on plantar aspect of foot, written only in the English language and that are publicly available, since 2000 to 2023

| Patient | Age | Sex | Site (sole) | Associated disease | Macroscopic size (cm) | Histopathology | Lymph node | Treatment |

| 1 (4) | 76 | M | L | none | 2.5 × 20 | nodular | no | Wide local excision |

| 2 (5) | 61 | F | R | Klippel-Trénaunay syndrome | 21 x 10 | ulcertated, metatypic | unclear | Amputation and radiotherapy |

| 3 (5) | 61 | M | non recorded | 5 x 4 | mixed soild and morphea | no | Amputation | |

| 4 (6) | 65 | F | R | none recorded | 2 x 2 | atypical nodular | no | Wide local excision |

| 5 (7) | 69 | F | L | history of mutiple non-melanoma skin cancers | 1.5 | nodular | no | Mohs micrographic surgery |

| 6 (8) | 72 | F | L | history of trauma from a sea-urchin | 2 | infilitrative | no | Unclear |

| 7 (9) | 69 | M | none recorded | 1.5 | Radiotherapy | |||

| 8 (10) | 46 | F | Xeroderma pigmentosum | 0·5 ×0·6 | infilitrative | n/a | Unclear | |

| 9 (11) | 80 | F | exposure to radiation from a shoe-fitting fluoroscope | unclear | infilitrative | unclear | Mohs micrographic surgery | |

| 10 (12) | 84 | F | L | history of trauma self-inflicted | 1.5 | infilitrative | no | Wide local excision |

| 11 (13) | 55 | F | L | none recorded | 1.2 X 1.3 | ulceraed, superifical | no | Wide local excision |

| Patient | Age | Sex | Site (sole) | Associated disease | Macroscopic size (cm) | Histopathology | Lymph node | Treatment |

| 1 (4) | 76 | M | L | none | 2.5 × 20 | nodular | no | Wide local excision |

| 2 (5) | 61 | F | R | Klippel-Trénaunay syndrome | 21 x 10 | ulcertated, metatypic | unclear | Amputation and radiotherapy |

| 3 (5) | 61 | M | non recorded | 5 x 4 | mixed soild and morphea | no | Amputation | |

| 4 (6) | 65 | F | R | none recorded | 2 x 2 | atypical nodular | no | Wide local excision |

| 5 (7) | 69 | F | L | history of mutiple non-melanoma skin cancers | 1.5 | nodular | no | Mohs micrographic surgery |

| 6 (8) | 72 | F | L | history of trauma from a sea-urchin | 2 | infilitrative | no | Unclear |

| 7 (9) | 69 | M | none recorded | 1.5 | Radiotherapy | |||

| 8 (10) | 46 | F | Xeroderma pigmentosum | 0·5 ×0·6 | infilitrative | n/a | Unclear | |

| 9 (11) | 80 | F | exposure to radiation from a shoe-fitting fluoroscope | unclear | infilitrative | unclear | Mohs micrographic surgery | |

| 10 (12) | 84 | F | L | history of trauma self-inflicted | 1.5 | infilitrative | no | Wide local excision |

| 11 (13) | 55 | F | L | none recorded | 1.2 X 1.3 | ulceraed, superifical | no | Wide local excision |

Case reports of BCC found on plantar aspect of foot, written only in the English language and that are publicly available, since 2000 to 2023

| Patient | Age | Sex | Site (sole) | Associated disease | Macroscopic size (cm) | Histopathology | Lymph node | Treatment |

| 1 (4) | 76 | M | L | none | 2.5 × 20 | nodular | no | Wide local excision |

| 2 (5) | 61 | F | R | Klippel-Trénaunay syndrome | 21 x 10 | ulcertated, metatypic | unclear | Amputation and radiotherapy |

| 3 (5) | 61 | M | non recorded | 5 x 4 | mixed soild and morphea | no | Amputation | |

| 4 (6) | 65 | F | R | none recorded | 2 x 2 | atypical nodular | no | Wide local excision |

| 5 (7) | 69 | F | L | history of mutiple non-melanoma skin cancers | 1.5 | nodular | no | Mohs micrographic surgery |

| 6 (8) | 72 | F | L | history of trauma from a sea-urchin | 2 | infilitrative | no | Unclear |

| 7 (9) | 69 | M | none recorded | 1.5 | Radiotherapy | |||

| 8 (10) | 46 | F | Xeroderma pigmentosum | 0·5 ×0·6 | infilitrative | n/a | Unclear | |

| 9 (11) | 80 | F | exposure to radiation from a shoe-fitting fluoroscope | unclear | infilitrative | unclear | Mohs micrographic surgery | |

| 10 (12) | 84 | F | L | history of trauma self-inflicted | 1.5 | infilitrative | no | Wide local excision |

| 11 (13) | 55 | F | L | none recorded | 1.2 X 1.3 | ulceraed, superifical | no | Wide local excision |

| Patient | Age | Sex | Site (sole) | Associated disease | Macroscopic size (cm) | Histopathology | Lymph node | Treatment |

| 1 (4) | 76 | M | L | none | 2.5 × 20 | nodular | no | Wide local excision |

| 2 (5) | 61 | F | R | Klippel-Trénaunay syndrome | 21 x 10 | ulcertated, metatypic | unclear | Amputation and radiotherapy |

| 3 (5) | 61 | M | non recorded | 5 x 4 | mixed soild and morphea | no | Amputation | |

| 4 (6) | 65 | F | R | none recorded | 2 x 2 | atypical nodular | no | Wide local excision |

| 5 (7) | 69 | F | L | history of mutiple non-melanoma skin cancers | 1.5 | nodular | no | Mohs micrographic surgery |

| 6 (8) | 72 | F | L | history of trauma from a sea-urchin | 2 | infilitrative | no | Unclear |

| 7 (9) | 69 | M | none recorded | 1.5 | Radiotherapy | |||

| 8 (10) | 46 | F | Xeroderma pigmentosum | 0·5 ×0·6 | infilitrative | n/a | Unclear | |

| 9 (11) | 80 | F | exposure to radiation from a shoe-fitting fluoroscope | unclear | infilitrative | unclear | Mohs micrographic surgery | |

| 10 (12) | 84 | F | L | history of trauma self-inflicted | 1.5 | infilitrative | no | Wide local excision |

| 11 (13) | 55 | F | L | none recorded | 1.2 X 1.3 | ulceraed, superifical | no | Wide local excision |

Case presentation

A 42-year-old Caucasian female presented with a lesion located on the mid-arch of her left foot. She first noted the lesion in her early 20s. She reported her occupation for the last 20 years, required her to wear constrictive construction boots throughout the day which this resulted in friction to her feet and moisture retention. She attended multiple GP appointments as the lesion grew larger and more pruritic. The lesion was diagnosed as athlete’s foot, and she was repeatedly prescribed topical antifungal ointments. She reported no personal or family history of skin cancers and was not exposure to other risk factors such as radiation or arsenic. In 2022, she was referred to dermatology where a punch biopsy confirmed the lesion was a BCC histologically.

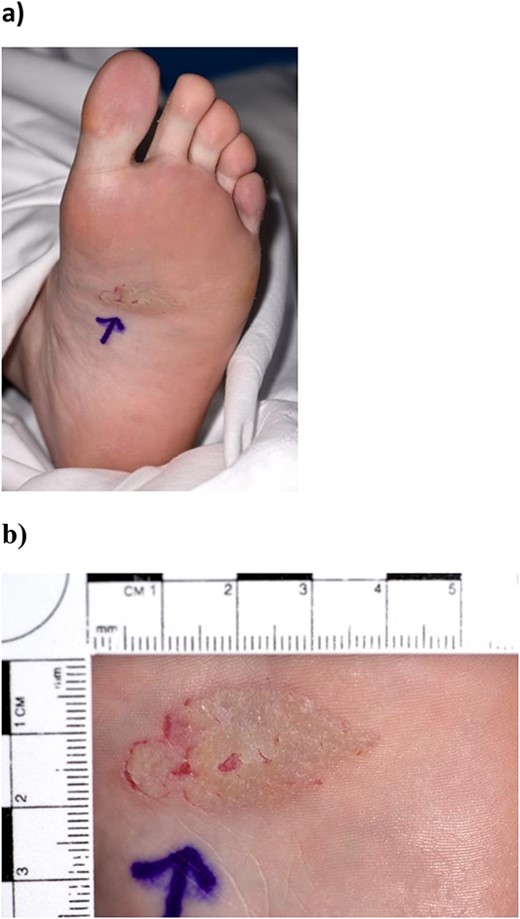

On clinical examination, a well-circumscribed, asymmetric, hyperkeratotic plaque measuring 3.3×2 cm was observed on the mid-arch of her left foot (Fig. 1a and b). There was no regional lymphadenopathy, and systemic examination was unremarkable with no other skin lesions.

(a, b) Preoperative image of basal cell carcinoma on the sole of the foot, measuring 3.3×2 cm.

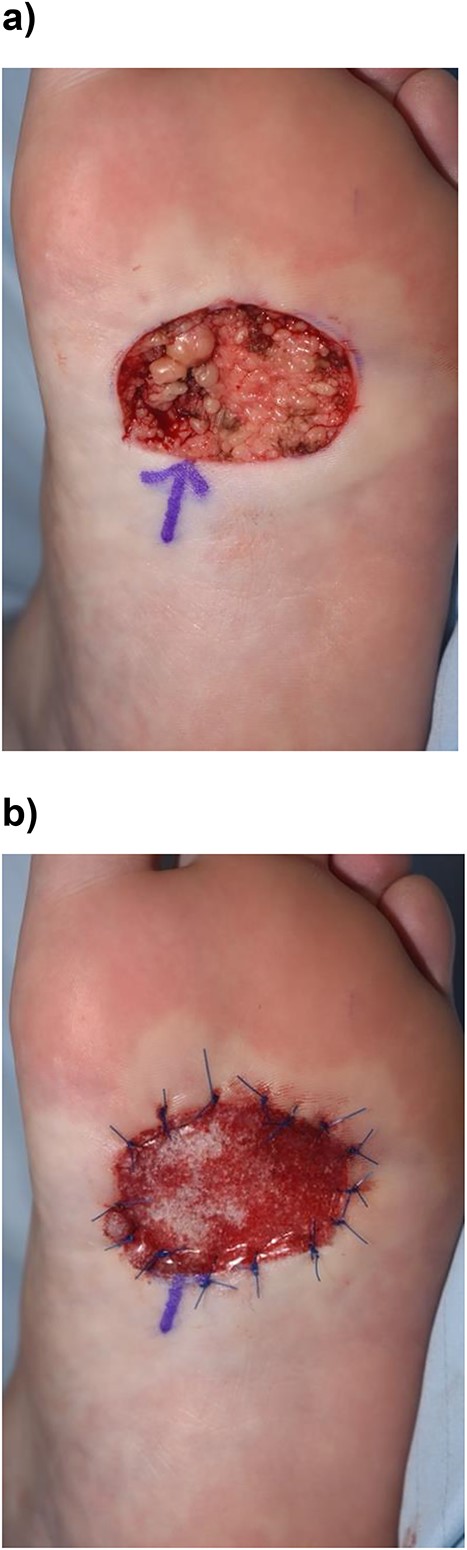

The patient was referred to the plastic surgery team who performed a wide local excision of the lesion and reconstruction of the defect. The lesion was marked with 5 mm margins using 3.5× loupe magnification under theatre lighting. The lesion was excised under a regional anaesthetic which was performed to the depth of the plantar fascia. Biodegradable Temporizing Matrix (Novosorb® BTM), a synthetic polyurethane dermal matrix was used to reconstruct the defect at the time of excision and secured using 3/0 prolene sutures (Fig. 2a and b). The patient was instructed to wear an ankle boot post-operatively to minimize shear stress to the wound and prescribed a dose of 5000 units of dalteparin daily for 6 weeks.

(a) Lesion was excised the depth of the plantar fascia. (b) Biodegradable Temporizing Matrix (Novosorb® BTM) covering the defect.

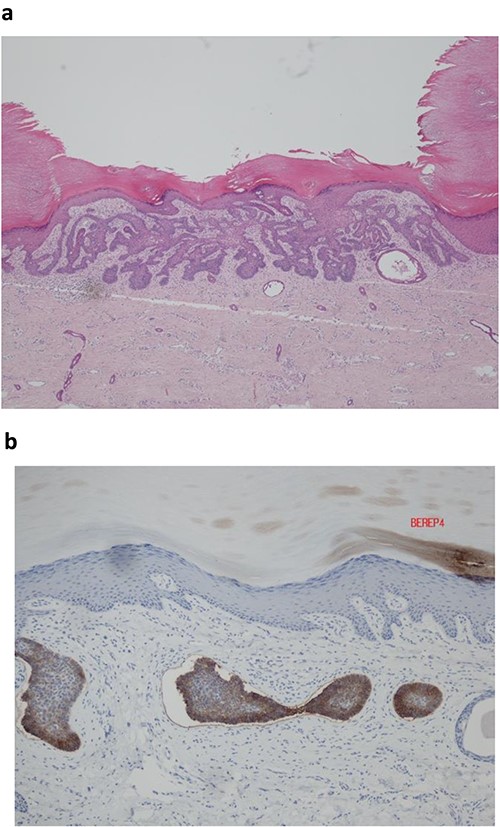

Histopathological analysis revealed that the tumour was a BCC with nodular and superficial patterns, with positive staining for BerEP4 immunostain (Fig. 3a and b). Peripheral palisading and clefting artefact was observed. There was no malignant squamous differentiation, lymphovasular or perineural space invasion. The tumour was completely excised with a 3 mm peripheral margin and 3 mm deep margin.

(a) Histopathological analysis showed an acral type skin containing a basaloid tumour with peripheral palisading and clefting artefact. (b) Ber EP4 immunohistochemistry positive.

Following histological disease clearance, the patient underwent the second stage of reconstruction seven weeks later. This involved harvesting a split-thickness skin graft from the lateral thigh using an air dermatome 10/1000 thickness. The donor site and the left sole were dressed (Fig. 4). The patient successfully recovered and was able to bear weight on her left foot without any complications (Fig. 5).

Split thickness skin graft covering defect and secured using 3/0 prolene sutures.

Discussion

The primary etiological factor associated with the development of BCC is UV radiation, as evidenced by its high incidence in sun-exposed areas, particularly the centrofacial region [1,14]. An alternative hypothesis suggests that BCCs may originate from hair follicle keratinocytes, which could explain their higher occurrence in non-glabrous skin regions [14]. Cells acquire malignant characteristics via mutations in genes which deregulate cell signalling and programmed death [15]. BCCs exhibit sustained proliferative signalling due to mutations in genes such as PTCH1 and SMO, which are part of the hedgehog signalling pathway [14]. Growth suppressors are evaded through mutations in tumour suppressor genes such as TP53, leading to uncontrolled cell proliferation [14]. However, the aetiology of BCC in extra-facial regions, such as the sole of the foot, is not fully understood as these areas receive less UV radiation exposure and consist of glabrous skin. Previous research suggests that the development of BCC in less sun-exposed areas may be associated with inherited disorders like basal nevus syndrome, exposure to radiotherapy or immunosuppression [6]. However, with our patient and most of the cases identified in the literature search, there were no significant associated risk factors [4–6, 8, 9, 12, 13]. Other rare differentials to consider when examining atypical lesions on the sole of the foot are poromas, squamous cell carcinoma, and amelanotic melanomas [4]. Clinical evaluation may benefit from the use of a dermatoscope, and any non-healing lesion should be biopsied to exclude malignancy [4].

Repetitive trauma and viral infection are possible antecedent factors which may be implicated in the development of this patient’s BCC. Existing research has established a link between chronic trauma and the development of squamous cell carcinoma, as chronic irritation of epithelial cells can promote carcinogenesis [16]. Our patient’s long-standing history of friction from wearing construction boots could support this hypothesis. The literature search revealed two additional cases where BCC development was associated with a history of trauma [8, 9]. Only three retrospective cohort studies have examined the association between BCC development secondary to trauma and the limited number of patients in these studies makes it challenging to draw definitive conclusions [17–19]. Another factor to consider is whether a prior fungal infection could have contributed to carcinogenesis. Fungal infections have been recognized as aetiological factor in various cancers through mechanisms involving direct oncogenic effects of fungal toxins, however, none regarding the pathogenesis of BCC [20]. Therefore, further research is required to elucidate the underlying mechanisms of BCC occurrence in atypical locations such as the sole of the foot.

This patient underwent a two-staged surgical approach that adhered to the four pillars of oncological reconstruction: clearance, form, function, and patient satisfaction. The delayed diagnosis resulted in significant growth of the BCC, rendering primary closure after wide local excision impractical. Initially, a biodegradable temporizing matrix (BTM) was applied over the wound bed. The BTM acted as a temporary, synthetic skin, promoting neovascularization and tissue regeneration to optimize wound bed preparation for the subsequent integration of a split-thickness skin graft (SSG) [21]. The choice of an SSG over a full thickness skin graft was preferred due to its larger surface area for wound coverage, reducing the risk of graft contracture, and facilitating faster functional restoration. Other treatments for BCC on the foot are Mohs surgery, radiotherapy, and amputation, depending on the extent and invasion of the skin cancer. Recent prospective studies have explored the benefits of applying BTM in the reconstruction of diabetic foot wounds, reducing the need for more complex reconstructive surgeries like free flaps [21, 22].

Conclusion

Our case highlights the challenges in diagnosis and management of lesions on the sole of the foot. Clinicians should consider a wide range of differentials including cancerous lesions such as BCC. If any lesion is not responding to the treatment, a biopsy should be taken at the earliest possible stage for timely diagnosis and effective management.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Richard, Mr McKirdy and Dr Pandit for their support and guidance during the project.

Author contributions

Stuart McKirdy: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing—review & editing. Dinithi Liyanage: Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. Richard Clough: Supervision, Writing—review & editing. Deepa Pandit: Writing—review & editing.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Funding

None of the authors has a financial interest in any of the products, devices, or drugs mentioned in this manuscript. No funding was sought or received for this work.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained for the publishing of the image/case described in this report.

References

McDaniel B, Badri T, Steele RB.