-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Mehrqand Shahid, Lakna H Alawattegama, Sherif A Latif, Matthew A Popplewell, Andrew Garnham, Michael L Wall, A case of pseudoaneurysm of the marginal artery of Drummond post-open abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) repair, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2024, Issue 11, November 2024, rjae706, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjae706

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

We present the first published account of a pseudoaneurysm of the Marginal artery of Drummond (MAoD) following an emergency open surgical repair of an inflammatory abdominal aortic aneurysm, in which the inferior mesenteric artery was ligated. This was hypothesized to be an iatrogenic injury secondary to retraction of the colonic mesentery during dissection of the aneurysm neck. The risk of pseudoaneurysm growth and rupture versus bowel ischaemia were evaluated in the post-operative phase. Ultimately, the patient underwent successful interventional embolization of the MAoD with no signs of bowel ischaemia post-intervention.

Introduction

A pseudoaneurysm is an interruption in the artery wall, most often due to injury, resulting in leaking of blood, which is contained by the tunica adventia or the surrounding perivascular tissue [1]. The pseudoaneurysm lumen is in direct communication with the arterial lumen, meaning it can continue to grow and is at risk of perforation [1].

The Marginal artery of Drummond (MAoD) is the main anastomotic artery joining the superior mesenteric artery (SMA) and the inferior mesenteric artery (IMA) which provides collateral circulation for the transverse and descending colon [2–4]. If for any reason the IMA is occluded or ligated (such as commonly during open abdominal aortic aneurysm repair), then the MAoD becomes the main circulatory blood supply of the left colon. If there is then a compromise to the MAoD, there is a high risk of consequent bowel ischaemia [2, 3, 5].

This report describes a case of presumed iatrogenic pseudoaneurysm in the MAoD caused by a retraction injury during open surgical repair of an abdominal aortic aneurysm (OSR AAA).

Case report

A 58-year old man was referred from a district general hospital overnight, with a 24-hour history of left sided flank/back pain and a pulsatile central mass. A CT Abdomen reported a 5.7 cm infrarenal AAA. He is an ex-smoker of 20 pack years with a background of hypertension and angina. Initial examination found the patient conscious and alert with a soft abdomen, severe epigastric and left iliac fossa tenderness and a pulsatile epigastric mass.

Discussion with two vascular interventional radiology consultants deemed the aneurysm to be an impending/contained rupture. It was not suitable for endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR) due to the short and tortuous aneurysm neck, therefore, the patient underwent emergency open AAA repair. Intraoperatively, the aneurysm was not ruptured but found to be an inflammatory aneurysm with impending rupture points. A standard inlay graft repair was performed and the IMA was ligated with no signs of bowel ischaemia on closing the abdomen. The patient was admitted to Intensive Care Unit (ICU) postoperatively, before stepping down to a vascular monitored bed 2 days later as he progressed well.

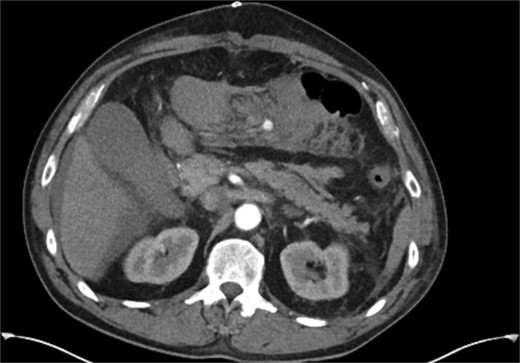

On day five post-operatively, the patient deteriorated, developing hypotension, diaphoresis, a new oxygen requirement, and complaining of new onset back pain. This is in conjunction with a drop in haemoglobin (Hb) from 129 g/L (day one post-operatively) to 89 g/L on Day 5. An abdominal CT Angiogram was performed, showing a pseudoaneurysm of the Marginal artery of Drummond measuring 1.2 × 1 × 1 cm (AP × TR × CC) with some surrounding haematoma in the small bowel mesentery (see Fig. 1). Following multi-disciplinary team (MDT) discussion, three possible management options arose: observe and re-scan the following day and optimize Hb, embolize the artery (although this has a risk of bowel infarction) or to resect the bowel. We decided to adopt a watch-and-wait approach and repeat the CTA the following day, which showed no significant change in the pseudoaneurysm. He was discharged home on Day 6 post-operatively.

CT angiogram performed on 5th postoperative day, demonstrating a small false aneurysm (1.2 × 1 × 1 cm) arising from the marginal artery of Drummond.

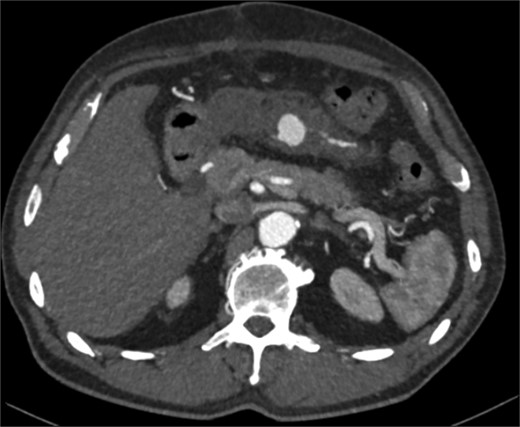

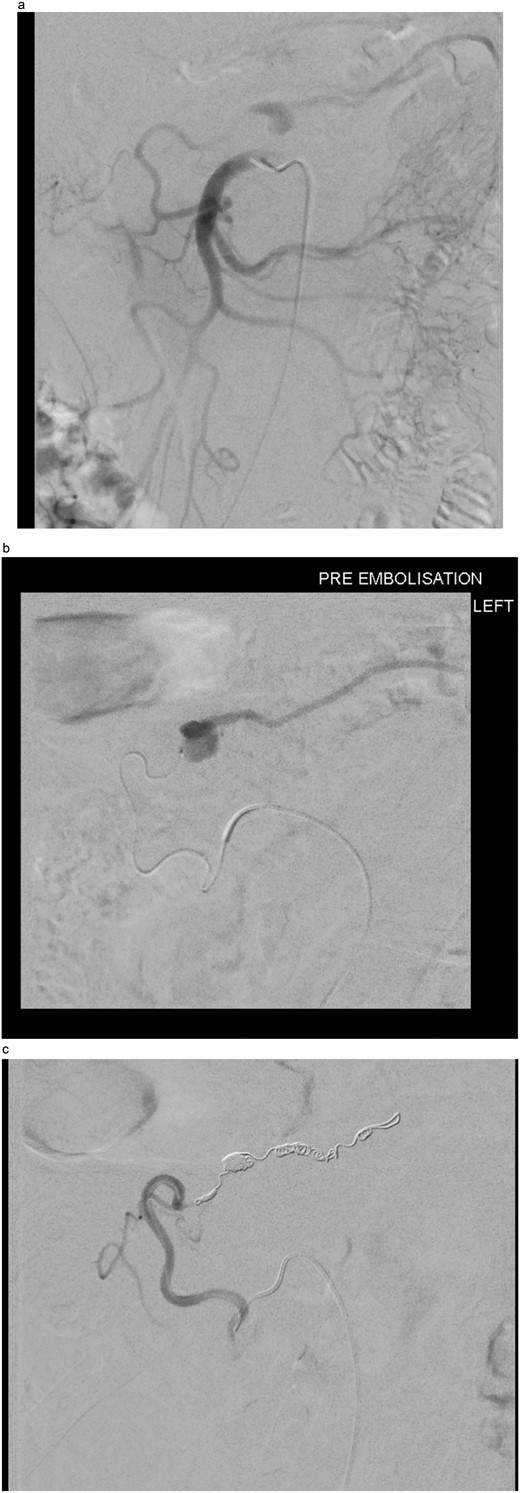

The two-week interval CTA showed that the pseudoaneurysm had increased in size to 2.1 × 1.8 × 1.8 cm (AP × TR × CC) (see Fig. 2). Whilst acknowledging the high risk of gut ischemia, the MDT agreed that intervention was necessary to avoid the risk of rupture. Eight weeks after initial pseudoaneurysm diagnosis, he underwent successful embolization of the MAoD. The embolization procedure was challenging due to tortuosity of the vessel and at the time, deemed too tortuous to stent on table, therefore embolization performed with microcoils (see Fig. 3). He remained clinically asymptomatic with a soft abdomen and had an overnight stay with the general surgery team on standby. His lactate remained insignificant overnight. He opened his bowels and managed a normal diet and was therefore discharged home the following day.

Interval CT angiogram demonstrating enlargement of the false aneurysm (2.1 × 1.8 × 1.8 cm).

(a) Digital subtraction angiogram (DSA) image taken from the SMA, demonstrating the pseudoaneurysm arising from the marginal artery of Drummond. (b) Microcatheter within the marginal artery of Drummond demonstrating the pseudoaneurysm. (c) Post-embolization image with four microcoils and successful occlusion of the pseudoaneurysm.

Discussion

A pseudoaneurysm of the marginal artery of Drummond is not a known complication of open AAA repair. On review of the literature, only a single similar case report was found, which discussed a Riolan arch pseudoaneurysm following EVAR [6], which is not relevant to our case. Therefore, we can conclude that there are no reported cases of MAoD pseudoaneurysms post-open AAA repair.

We hypothesize that in our case, the pseudoaneurysm is iatrogenic secondary to a retraction injury which arose during exposure and repair of the AAA. As the OSR AAA was emergency surgery, we presume the iatrogenic injury was sustained on developing exposure of the AAA neck whilst applying retraction to the colonic mesentery, complicated by the challenging dissection of the inflammatory aneurysm. Furthermore, many studies discuss and evidence the considerable variability of the presence and morphology of the MAoD [2, 5, 7–10]. Such variations can be attributed to the body’s response to disease or simply be congenital [11–13]. It can therefore be stated that the MAoD is at risk of sustaining iatrogenic injury [2].

With the IMA ligated intra-operatively, the MAoD was now the only visible vessel on CT providing blood supply to the descending colon. Stenting of the MAoD was considered however we felt this may not be possible due to tortuosity of the vessel in addition to the low likelihood of a stent so small remaining patent. The team was aware that there was a risk of bowel ischaemia developing by embolizing the MAoD [3]. In order to mitigate this risk as much as possible the procedure was completed after an eight-week interval. It was hoped that this would encourage collateralization to the bowel from the branches of the Internal Iliac artery as well as allowing the inflammation from the OSR AAA to settle, therefore hopefully reducing the risk of ischaemic bowel. The team was aware that if the abdominal cavity needed to be re-opened for a bowel resection due to ischaemia then a delay would allow the abdominal compartment to settle from the first laparotomy. It was hoped that it would reduce the risk of any further iatrogenic injury during re-laparotomy, had it been required. If other centres were to come across another case of pseudoaneurysm of MAoD then we hope this case would help guide in the planning of interventions to treat this complication.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Funding

None declared.