-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Tom Vandaele, Lisa Dekoninck, Pauline Vanhove, Bart Devos, Mathieu Vandeputte, Marc Philippe, Johan Vlasselaers, Rectal stercoral perforation: an uncommon anatomical localization of a rare surgical emergency, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2024, Issue 1, January 2024, rjad704, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjad704

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

A stercoral rectal perforation is an uncommon cause of acute abdominal pain with only limited cases documented in medical literature. Timely and accurate imaging is essential when this condition is suspected, and immediate surgical intervention is imperative upon confirming the diagnosis of bowel perforation. Usually, the definitive diagnosis of a stercoral rectal perforation is established intraoperatively and a Hartmann procedure with (temporary) end colostomy is performed. In this case report, we present our first-hand experience in managing a stercoral rectal perforation, highlighting the importance of early diagnosis and rapid surgical intervention to achieve favorable outcomes.

Introduction

Stercoral perforations are rare surgical emergencies associated with significant morbidity and mortality. To date, published literature contains <150–200 documented cases of stercoral perforations, predominantly occurring in the sigmoid colon and rectosigmoid junction [1, 2]. A rarer subgroup of stercoral perforations is localized in the rectum [2], but data regarding this subgroup are limited. In this case report, we present our experience in managing a rectal stercoral perforation.

Case report

A 62-year-old female patient presented at the emergency room with sudden-onset severe abdominal pain. The patient has a medical history of Stage IV breast cancer with bone metastasis (T3N1M1), diagnosed 6 years ago. She initially received neo-adjuvant treatment with Letrozole and Palbociclib, resulting in complete remission except for residual metabolic activity in the left breast. Subsequently, a mastectomy was performed and adjuvant treatment with Letrozole and Palbociclib was continued post-surgery. The patient did not have a history of constipation or any other gastro-intestinal problems prior to her emergency room visit.

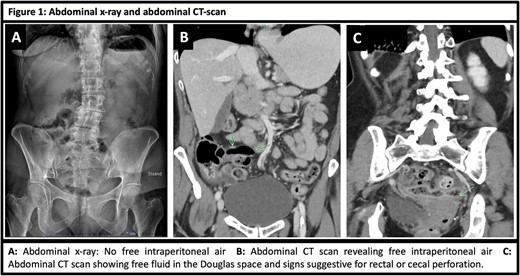

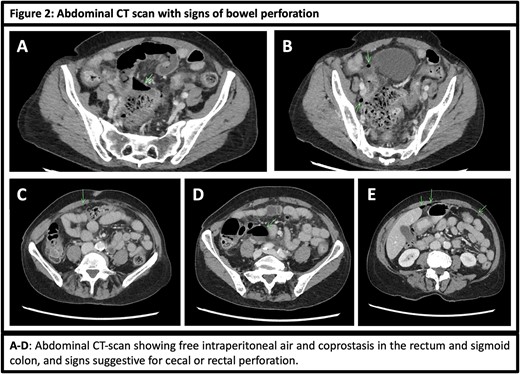

Currently, the patient presents with diffuse, sudden-onset severe abdominal pain along with nausea and vomiting. Clinical examination revealed abdominal tenderness with signs of peritonitis. Laboratory tests showed mild macrocytic anemia (hemoglobin 10.6 g/dl), mild leukocytopenia (white blood cell count: 3310/mcl as a consequence of Palbociclib), and a slightly increased lactate level (2.3 mmol/l). Abdominal X-ray showed no abnormalities (Fig. 1A), but abdominal CT scan revealed signs of bowel perforation, with free intraperitoneal air and fluid in the lower abdomen and pelvis (Figs 1B and C and 2A–E). The sigmoid colon and cecum showed segmentary hypercaptation and bowel wall thickening on abdominal CT scan, suspicious for a bowel perforation at those sites (Fig. 1C).

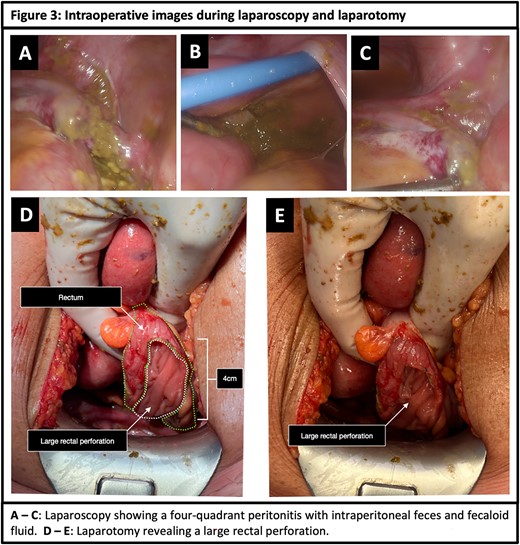

An urgent exploratory laparoscopy was performed, confirming the diagnosis of a bowel perforation and revealing extensive abdominal contamination with fecaloid fluid and feces dispersed throughout the abdominal cavity (Fig. 3A–C). A subsequent laparotomy was performed to thoroughly irrigate the abdominal cavity and inspect the entire gastrointestinal tract. During inspection, large fecalomas were found in the abdominal cavity and rectum along with a large rectal tear (~4 cm) at the antimesenteric side of the middle one-third of the rectum (Fig. 3D and E). Furthermore, a pressure ulcer caused by a fecaloma located 1 cm below the perforation site was identified. Based on these findings, a Hartmann procedure was performed with partial resection of the rectum and rectosigmoid junction, and a temporary end colostomy was constructed.

Following surgery, the patient received intravenous Meropenem for 5 days due to a high risk for severe infections as a result of her immunosuppressants. Postoperatively, she was monitored in the intensive care unit for 1 day and experienced an episode of atrial fibrillation on day 3. The remainder of her hospital stay was uneventful, with rapid recovery of gastrointestinal transit and proper functioning of the colostomy. The patient was discharged home on postoperative day 9. Additionally, the patient was advised to increase fiber, fruit, and fluid intake, and use Macrogel laxatives to minimize the risk of relapse.

Pathological examination of the resected rectum indicates the presence of peritonitis, but it revealed no other abnormalities apart from a perforation and rectal ulcer.

Discussion

Stercoral colonic perforations are rare. The first case of a stercoral perforation dates back to 1984 by Berry J [2, 3], .and currently, around 150–200 cases have been published in literature [2]. The overwhelming majority of stercoral perforations are located in the sigmoid colon or at the rectosigmoid junction [4]. Rectal stercoral perforations, on the other hand, are exceedingly rare and account for <10% of all stercoral perforation [5]. A thorough search in the PubMed and Embase database revealed <15 published cases.

The diagnosis of a rectal perforation is typically suspected on abdominal CT scan. It is worth noting that an abdominal x-ray may appear normal in patients with a rectal perforation as demonstrated in this case [2, 6–8]. The definitive diagnosis of rectal perforation is typically made intraoperatively. Diagnostic criteria for stercoral perforations proposed by Maurer et al include (i) a round or ovoid colonic perforation exceeding 1 cm in diameter; (ii) the colonic perforation is located at the anti-mesenterial side; (iii) presence of fecalomas within the colon, protruding through the perforation site, or found within the abdominal cavity; (iv) microscopic evidence of pressure necrosis, ulcerations, and/or a chronic inflammatory reaction around the perforation site; and (v) absence of abdominal trauma or other colonic pathologies [6, 9].

Clinically, a patient with a rectal perforation above the peritoneal lining presents with sudden onset of abdominal pain that progresses to a rigid abdomen with four-quadrant peritonitis and sepsis [6]. Multiple risk factors have been associated with stercoral perforations, including geriatric patients, patients with psychiatric disorders, immobile patients, narcotic-dependent patients, patients with a history of constipation, the use of certain medications such as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, anti-depressants, and tranquilizers [2, 4]. Underlying medical conditions, such as diabetes mellitus, Parkinson’s disease, stroke, and hypothyroidism, can also contribute to the risk [2, 4]. The underlying mechanism of perforation usually involves local bowel ischemia from pressure caused by one or multiple large fecalomas [2, 4, 6, 10].

Stercoral perforations are usually managed by a Hartmann resection with end colostomy [11, 12]. Depending on the amount of fecal soiling, the extent of disease, the accessibility of the abdomen, and the experience of the surgeon, the procedure can be performed via a laparotomy or a laparoscopic approach. It is important that a rectal perforation is diagnosed early and treated promptly because a delay in diagnosis and definitive treatment is associated with significant mortality [6].

Further management after hospital discharge should be focused on preventive measures to avoid recurrence, including dietary changes (increasing fiber, fruit and fluid intake), medication adjustments, and the use of laxatives [13].

In conclusion, a rectal stercoral perforation is a rare surgical emergency associated with significant mortality if not diagnosed promptly and treated adequately. This case report details the successful management of a stercoral rectal perforation in a 62-year-old female successfully treated by an emergency Hartmann procedure. Through this report, we emphasize the importance of timely diagnosis and early surgical intervention, while highlighting the potential for favorable outcomes in managing these rare, urgent, and often challenging cases.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all members of the AZ Zeno department of general surgery, radiology, pathology, and anesthesiology for their contribution.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding

None declared.

Disclosures

Tom Vandaele, Lisa Dekoninck, Pauline Vanhove, Bart Devos, Mathieu Vandeputte, Marc Philippe, and Johan Vlasselaers have no disclosures to declare.