-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Tatsuya Mutou, Satoru Kira, Ryota Furuya, Takanori Mochiduki, Norifumi Sawada, Takahiko Mitsui, A case of proximal migration of a double-J ureteral stent in a patient with metastatic gastric cancer, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2023, Issue 8, August 2023, rjad488, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjad488

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Ureteral stenting is a common procedure to relieve ureteral obstructions. There are few reports regarding the proper migration of the proximal coil of a double-J ureteral stent into the ureter. Herein, we report a case of proximal stent migration after stent placement for ureteral stenosis caused by a malignant tumor in the gastrointestinal tract.

Introduction

Ureteral stenting is a common procedure used by urologists to prevent or relieve ureteral obstruction in general practice. A double-J stent is anchored proximally to the renal pelvis and distally to the bladder due to its two-coil design. Ureteral stents rarely migrate to the proximal side [1]. However, if a ureteral stent migrates, it is often necessary to remove or replace the stent properly, which is burdensome for the patient.

Herein, we report a case of proximal stent migration after stent placement for ureteral stenosis caused by a malignant tumor in the gastrointestinal tract.

Case report

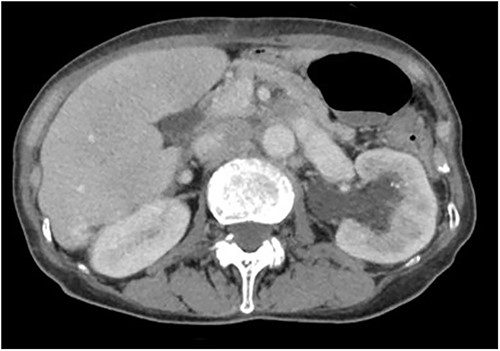

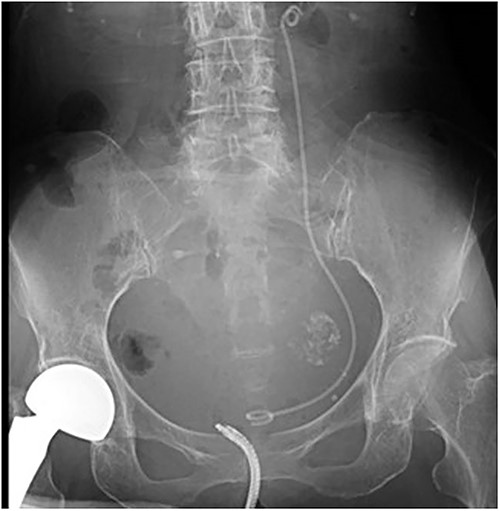

A 78-year-old woman (height, 161 cm; weight, 35 kg) had undergone total gastrectomy for gastric cancer; pathological examinations had revealed signet ring cell carcinoma with invasion into the serosa. One year and 4 months after the surgery, she presented to our hospital with fever, anorexia and weight gain. Computed tomography (CT) revealed left ureteral stricture and hydronephrosis caused by recurrent peritoneal dissemination (Fig. 1). Blood tests revealed decreased renal function and an increase in the inflammatory response. Based on these findings, a diagnosis of left obstructive acute pyelonephritis was made, prompting a decision to place a ureteral stent to relieve the obstruction. Using a flexible cystoscope fluoroscopically, a 6 Fr, 24 cm double-J ureteral stent was inserted into the left ureter. The guidewire passed smoothly, and good coiling was achieved both proximally and distally with no apparent complications (Fig. 2). Two weeks after stent placement, the patient recovered with improvements in left hydronephrosis and renal function.

A post-operative plain abdominal X-ray; the ureteral stent is properly placed as seen in a plain abdominal X-ray.

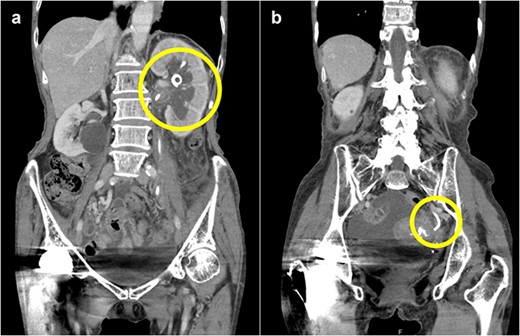

Forty-five days after the stent placement, the patient visited the emergency department complaining of fever and hematuria. CT showed that the left hydronephrosis had reappeared, and the lower end of the stent had migrated into the ureter (Fig. 3a and b). Blood tests revealed a worsening of renal function and a prominently elevated inflammatory response. Due to the diagnosis of relapse of left obstructive acute pyelonephritis caused by the migration of the ureteral stent, an emergency nephrostomy was performed promptly, and antibiotic treatment was started. The patient was discharged after 2 weeks of hospitalization.

Abdominal CT scan; (a) CT demonstrates the position of proximal coil formation in the left renal pelvis; (b) CT demonstrates proximal stent migration into the ureter.

After 1 month, we replaced the migrated ureteral stent with a new 7 Fr, 26 cm double-J ureteral stent. After confirming successful postoperative urine drainage through the stent, the nephrostomy tube was removed the day after the procedure. Thereafter, the patient experienced no relapse of the left hydronephrosis or obstructive acute pyelonephritis.

Discussion

It is considered that proximal migration of ureteral stents is associated with inappropriate stent length, poor positioning or incorrect deployment of the stent [2]. In this case, we assumed the possibility of inappropriate stent length.

Generally, the estimation of ureter length for stent selection is based on height and sex in general practice; this method was followed in this case as well. However, recent studies have shown that the aforementioned factors have little correlation with the true ureteral length [3]. A previous study reported a trend toward the selection of shorter stents, as well as a trend toward smaller stent length-to-true ureter length ratios, in the migrating stent group than in the non-migrating stent group [1]. When the stent length is inadequate, the stent may migrate during proximal coil formation or respiratory movement of the kidney. Therefore, stent length should be determined not only based on height or sex but also with reference to prior CT measurements, retrograde pyelography during stenting or actual measurements using a ureteral catheter.

To position the ureteral stent properly, it is necessary to ensure its correct coiling in the renal pelvis. If coil formation in the renal pelvis was unsuccessful, the stent was placed back into the ureter with the pulling string attached and then advanced into the renal pelvis again. A previous study showed that if the proximal coil forms in the upper renal calyx, a stent longer than the expected ureteral length is required [4]. Additionally, the study reported that in such cases, the possibility of migration due to respiratory fluctuations of the kidney is increased [4]. In addition, if the expansion of the renal pelvis and ureter is released by stenting, the renal pelvis may shrink and the coil may enter the upper renal calyx. Thus, it is important to drain all urine from the renal pelvis before stenting and perform a pyelogram with the hydronephrosis released to confirm the morphology of the renal pelvis.

Conclusion

The risk of proximal migration during ureteral stent placement is low. However, if a ureteral stent migrates, it can be burdensome for the patient. Thus, the appropriate estimation of stent length and proximal coil formation in the proper position for each patient should be carefully considered.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.jp) for English language editing.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Funding

This study did not receive any specific grants from funding agencies in the public, commercial or non-profit sectors.

Data availability

The data can be retrieved by emailing the corresponding author.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report.