-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Sadaf Davoudi, Marjolein De Decker, Paul Willemsen, Atypical fundal perforation: a case report, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2023, Issue 8, August 2023, rjad480, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjad480

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Gastric perforations typically occur in the distal stomach, along the greater curvature or the antrum. The vast majority of upper gastrointestinal (GI) perforations are caused by peptic ulcer disease. We present a case of an atypical location of gastric perforation. A 31-year-old patient was experiencing nausea and severe abdominal pain. Explorative laparoscopy revealed a large fundal perforation. The patient underwent an abdominoplasty 5 days before with revisional surgery for hemorrhage. He had recently lost 42 kg after endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty (ESG) 8 months before. ESG is a minimally invasive alternative for bariatric surgery. Since its implementation, several studies have been published indicating the procedure as safe. However, some major adverse events, such as upper GI-bleeding, peri-gastric leak, and pneumoperitoneum, have been described. The atypical location of the perforation might be explained by a combination of events such as surgical stress, revisional surgery, major weight loss, and the history of ESG.

INTRODUCTION

Gastric perforation has various etiologies, nevertheless the vast majority is caused by spontaneous perforation because of peptic ulcer disease (PUD). PUD is common with a lifetime prevalence in the general population of 5–10%. Peptic ulceration occurs because of acid peptic damage leading to mucosal erosion. Complications of PUD include perforation and bleeding. Two important factors in the etiology of perforation are Helicobacter pylori (Hp) and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS) [1]. Infection with Hp is an important cofactor for the development of duodenal or gastric ulcers. Hp induces inflammation of the gastric mucosa, most pronounced in the antrum, which is nonacid-secreting leading to elevated release of gastrin. This will, in turn, stimulate excess acid secretion in the more proximal fundus, which is acid-secreting [2].

The localization of the ulcers gives an indication of the cause. Benign gastric ulcers occur predominantly on the lesser curve, whereas ulcers on the greater curve, fundus, and antrum are more commonly malignant [3].

We present a case of an atypical ulcerative fundal perforation, which was nonmalignant.

CASE REPORT

A 31-year-old male patient was admitted on the plastic surgery ward after he underwent an abdominoplasty for excessive skin and soft tissue. He had lost 42 kg after an endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty (ESG) 8 months before. His comorbidities included musculoskeletal back pain and arterial hypertension that was controlled with oral agents (Coversyl 5 mg/day).

The abdominoplasty went fluently. However, on postoperative Day 1, revisional surgery was performed for persisting bleeding. An evacuation of a hematoma of 500 ml took place; however, no bleeding focus was found.

The following days, the patient was experiencing severe nausea and vomiting. On postoperative Day 5, physical examination showed signs and symptoms of peritonitis with generalized abdominal pain, guarding and rebound tenderness. Blood results showed elevated inflammatory markers with C-reactive protein of 195,4 mg/l and anemia with hemoglobin of 9,4 g/dl.

CT abdomen revealed a large amount of free air throughout the abdomen, mostly localized anterior, but also perihepatic, perigastric, paracolic, and perisplenic (Figs 1 and 2).

CT abdomen showing a large amount of free air mostly localized anterior.

CT abdomen showing large amount of free air throughout the abdomen.

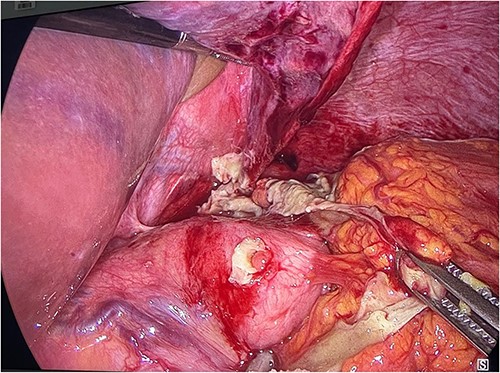

The patient was urgently referred to general surgery where he was taken to the operating theater for an exploratory laparoscopy. Three large strands of fibrinous exudate and pus were noticed at the umbilical and gastric fundus level. After detaching the strands, a large perforation was found localized on the fundus of the stomach just above the place of the U-shaped ESG-stitches (Fig. 3). The defect was closed with three interrupted Vicryl 3/0 sutures. Two surgical drains were placed on both sides subdiaphragmaticly. During the postoperative period, the patient was treated with intravenous antibiotics (amoxyclavulanic acid) and high dose proton pump inhibitors (PPI).

Laparoscopic visualization showing fibrinous strands at the level of the gastric fundus covering a fundal perforation.

The patient reported significant improvement of symptoms postoperatively.

The left subdiaphragmatic drain was removed on postoperative Day 3, as the right drain was removed 1 day later. The patient was discharged in good state on Day 4 with oral antibiotics and PPI’s. Six weeks postoperatively, gastroscopy showed a still persisting narrowing of the gastric lumen; however, one or two ESG stitches were found to be loose. Biopsies were taken to determine HP-status, which were found to be negative.

At the follow-up consultation 7 months after the event, the patient was doing well with a stable body weight.

DISCUSSION

The vast majority of spontaneous gastro-intestinal perforations are because of PUD. Two important factors in the development of perforated peptic ulcers are Hp and NSAIDS [1]. In our case, the patient had no usage of NSAIDS and gastric biopsies taken during gastroscopy preoperatively revealed Hp negativity and mild gastritis. The patient underwent an abdominoplasty for excessive skin after massive total body weight loss of 42 kg, 8 months after an ESG procedure.

Obesity is a still increasing global pandemic, affecting ~650 million in 2016, according to the World Health Organization. It is defined as a body mass index (BMI) ≥ 30 kg/m2. A high BMI is identified as a risk factor for many chronic diseases including diabetes mellitus type 2, cardiovascular diseases, chronic kidney diseases, many cancers and musculoskeletal disorders [4].

The current treatment options for obese patients are diet and lifestyle changes, pharmacotherapy (such as GLP-1 agonists) and, still seen as the most effective, bariatric surgery. In spite of the efficacy of bariatric surgery, only a small fraction eligible for these procedures decides for bariatric surgery [5]. Increasingly, major developments are seen in innovative treatment strategies such as endoscopic bariatric therapy as a novel minimally invasive approach to obtain body weight loss. ESG is an incisionless endoscopic minimally invasive therapy where the greater curvature of the stomach is plicated by full-thickness sutures as a way to reduce gastric capacity and delay gastric emptying [6]. In our case, a full thickness U-shaped suture pattern was used with four U-shaped stitches from the upper edge of the antrum over the greater curvature to the fundus as a first layer, with subsequently three U-shaped stitches over the first layer.

In a prospective study, Sharaiha et al. [7] proved that ESG achieves sustained body weight loss up to 24 months, as well as reduced markers of hypertension, diabetes, and hypertriglyceridemia. Although ESG is found to be a relatively safe procedure, some major adverse events are described.

Gastric perforation after ESG surgery is rare, in a meta-analysis of eight studies (n = 1859), two patients suffered gastric perforation (pooled incidence 0.54% CI 0.22–1.34) [8].

The main reason for gastric perforation that is described is iatrogenic injury.

A case report of Wright et al. noted caution regarding the use of argon plasma coagulation (APC) for marking of the suture line on the anterior and posterior stomach walls as two perforations because of APC were noticed 48 h after ESG on endoscopy. The perforations were located posteriorly on the suture line along the greater curvature [9].

Gastric perforation 5 days after ESG has been reported as well because of the fact that the full-thickness sutures had entered the anterior abdominal wall [10].

In our case, iatrogenic injury caused by instruments or diathermy was rather unlikely as the patient was stable postoperatively and presented with a gastric perforation 8 months postoperatively.

Stress-related mucosal damage (SRMD) describes the pathology of acute, erosive, inflammatory insults to the upper gastrointestinal tract that is associated with critical illness. The mechanism behind SRMD includes reduced gastric blood flow, mucosal ischemia, and reperfusion injury [11]. The stomach has a rich vascular supply with multiple collaterals making its vulnerability to ischemia rather poor. However, gastric ischemia can still present as acute or chronic abdominal pain [12].

The pathophysiology of stress ulcers starts from a state of critical illness, which leads to increased release of catecholamines decreasing the cardiac output and increasing vasoconstriction. These factors contribute to splanchnic hypoperfusion. Moreover, hypovolemia and the release of proinflammatory cytokines can intensify splanchnic hypoperfusion leading to acute stress ulceration. Endoscopic signs of SRMD can be multiple subepithelial petechiae and discrete ulceration, particularly in the gastric fundus [13].

The use of full-thickness sutures might contribute to the potential risk of inflammation or ulceration by excluding gastric mucosa in analog to ulcer perforation in the excluded stomach and duodenum as a rare complication after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass [14].

Bjorkman et al. described that ulceration might be a result of the fact that by excluding the stomach and duodenum, it is deprived of the buffering effect of ingested food and thereby, the produced acid in the excluded stomach remains unneutralized [15].

On detailed review of this case, this fundal location of perforation is likely to be a combination of local and systemic factors. The use of full-thickness sutures might contribute to the potential risk of inflammation or ulceration by excluding gastric mucosa. When additional stressors are added, such as surgical stress, revisional surgery, massive total body weight loss, this might provoke stress ulceration and gastric ischemia leading to gastric perforation. Routine postoperative gastroscopy after 6 months might be necessary to visualize possible histopathological changes.

CONCLUSION

The atypical location of the fundal perforation might be explained by a combination of stressful events such as surgical stress, revisional surgery, major total body weight loss and a history of ESG 8 months before.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

FUNDING

None.

References

- obesity

- surgical procedures, minimally invasive

- abdominal pain

- hemorrhage

- weight reduction

- ulcer

- endoscopy

- gastrointestinal bleeding

- gastroplasty

- laparoscopy

- nausea

- peptic ulcer

- surgical procedures, operative

- pneumoperitoneum

- stress

- abdominoplasty

- gastric ulcer perforation

- bariatric surgery

- distal stomach

- adverse event

- stomach perforation