-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Kirby Laslett, Kimberley Tan, Amardeep Gilhotra, Izhar-ul Haque, Pancreatic heterotopia of the gallbladder – possible cause of right upper quadrant pain, a case report, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2023, Issue 6, June 2023, rjad347, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjad347

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Pancreatic heterotopia is characterized by ectopic pancreatic tissue found outside the pancreas without any anatomical or vascular connection to the pancreas. Pancreatic heterotopia of the gallbladder is a rare histological finding; there have been only a handful of cases described in the literature. Pancreatic heterotopia of the gallbladder is usually diagnosed incidentally at histological examination following cholecystectomy or autopsy. Clinical presentation of pancreatic heterotopia of the gallbladder can vary from biliary colic, biliary obstruction or it can be completely asymptomatic. It has been suggested that gallbladder pancreatic heterotopia may lead to pancreatitis of this ectopic tissue, which may present differently to typical biliary colic. Here, we present the case of a 43-year-old male that presented with 2 years of significant postprandial nausea and right upper quadrant pain. Histopathology following cholecystectomy revealed chronic cholecystitis with cholelithiasis, in addition to a focus of pancreatic heterotopia in the gallbladder wall.

INTRODUCTION

Pancreatic heterotopia is a rare histological finding, characterized by ectopic pancreatic tissue found outside of the pancreas gland without any anatomical or vascular connection to the pancreas [1]. There have been only a handful of cases of ectopic pancreatic tissue found in the gallbladder described in the literature. Accessory pancreatic tissue can be found throughout the gastrointestinal tract; however, it is quite rare to find it in the gallbladder [2]. It has been suggested that pancreatitis of ectopic pancreatic tissue within the gallbladder could contribute to the clinical presentation and may present differently to typical biliary colic [3]. Here, we present a case of an incidental finding of heterotopic pancreatic tissue within the gallbladder, in a patient with an atypical presentation of biliary colic.

CASE REPORT

A 43-year-old male presented to the surgical outpatient clinic complaining of 2 years of symptoms consistent with biliary colic. His primary symptom was significant postprandial nausea, along with right upper quadrant abdominal pain, which lasted for a few hours and was relieved by vomiting. He was not jaundiced, had never had pancreatitis and denied any obstructive symptoms. He had no significant past medical history; he did not drink alcohol and had never been a smoker.

On examination, the patient appeared well, with normal vital signs. He was a slim gentleman, and abdominal examination at the time of outpatient clinic review revealed a soft and non-tender abdomen. Abdominal ultrasonography demonstrated a solitary gallstone measuring 20 mm, along with gallbladder sludge. The gallbladder wall was thickened without any pericholecystic fluid or probe tenderness, suggestive of chronic cholecystitis. Pre-operative blood tests were all normal, with a normal lipase, no deranged liver function tests and a normal bilirubin level. Gastroscopy was normal, with gastric biopsies also normal and negative for helicobacter pylori. The patient had been on esomeprazole for ~6 months prior to presentation to the surgical outpatient clinic, which had provided no improvement to his symptoms.

The patient underwent an elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy with intraoperative cholangiogram. The surgery was uncomplicated, intraoperatively it was found that the gallbladder was thick-walled with moderate omental adhesions, and the intraoperative cholangiogram demonstrated normal anatomy with no filling defects. The patient was well post-operatively and discharged home the same day.

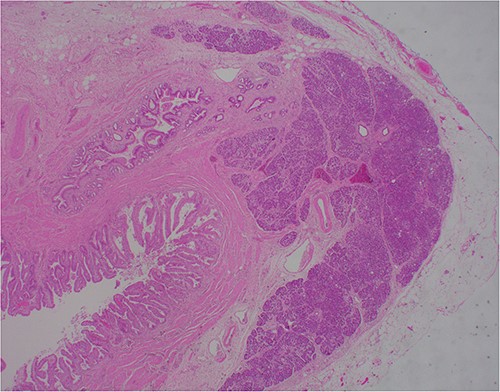

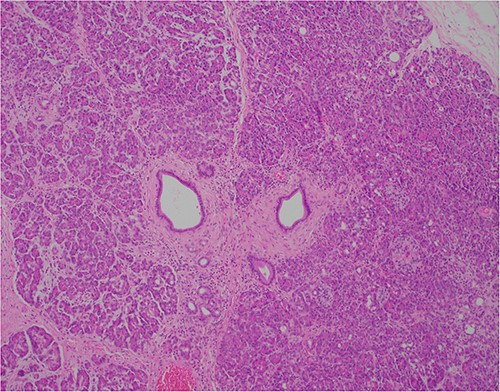

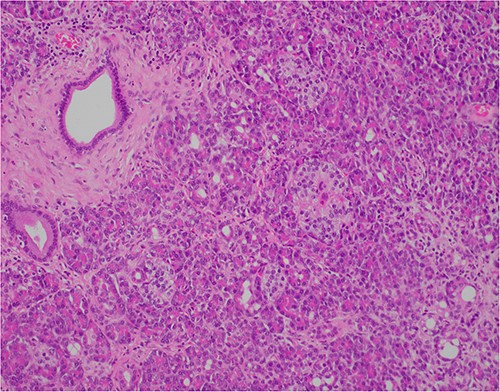

At outpatient phone clinic review 2 months post-surgery, the patient had recovered well, and his pre-operative symptoms of nausea, vomiting and pain had completely resolved. The histopathology of the gallbladder found chronic cholecystitis with cholelithiasis, in addition to a 6 mm focus of pancreatic heterotopia in the gallbladder wall. This heterotopic tissue contained acini, ducts and islet cells, classifying it as Type I pancreatic heterotopia (Figs 1–3).

×2 objective lens; low-magnification photograph showing an area of pancreatic heterotopia.

×10 objective lens; showing central duct with surrounding pancreatic acini and islets, with preserved architecture.

×20 objective lens; normal duct towards left hand side; acini (with dense pink cytoplasmic granules) and islets (clusters of pale cells).

DISCUSSION

Pancreatic heterotopia is a rare histological finding and is characterized by a growth of aberrant pancreatic tissue without any anatomical or vascular connection to the pancreas [1]. The incidence of pancreatic heterotopia is difficult to determine as it is mostly asymptomatic; however, it has been reported to be present in 0.1–13% of the general population [1, 2]. Ectopic pancreatic tissue can be found anywhere in the gastrointestinal tract; most commonly, it is found in the stomach and duodenum, and less commonly the jejunum, Meckel’s diverticulum, colon, oesophagus, gallbladder, common bile duct, spleen and mesentery [1, 2, 4].

The pathogenesis of pancreatic heterotopia is unknown, it is thought to arise during embryological development of the gastrointestinal tract. The normal pancreas develops from buds arising from the duodenum, which then fuse together [4, 5]. One possible theory for the pathogenesis of pancreatic heterotopia proposes that pancreatic tissue remaining in the wall of the duodenum is carried away from the developing pancreas and gives rise to accessory pancreatic tissue elsewhere in the alimentary tract, hence why it is more commonly found in the stomach and duodenum [4]. Another theory proposes the development of pancreatic metaplasia of endodermal tissues, which are localized to the submucosa along the digestive tract [4]. A recent theory suggests that abnormalities in the Notch signalling system, which is required for region appropriate pancreas cell differentiation, may lead to pancreatic heterotopia elsewhere in the gastrointestinal tract [6].

Gaspar-Fuentes described the classification system for pancreatic heterotopia in 1973, which consists of four types [2, 5]. This is a modification of the original classification system first described by Heinrich in 1909, which only consisted of three types [2]. Type I consists of typical pancreas tissue and contains acini, ducts and islet cells, the same as seen in normal pancreas tissue. Type II consists of pancreatic ducts only, also known as canalicular type. Type III consists of acinar tissue only, also known as exocrine type. Finally, Type IV consists of islet cells only, also known as endocrine type [2, 5].

Clinical presentation of pancreatic heterotopia of the gallbladder can vary from symptoms consistent with biliary colic or biliary obstruction; however, usually, it is completely asymptomatic [1, 2]. Pancreatic heterotopia of the gallbladder can only be diagnosed on histological examination of the gallbladder following cholecystectomy; currently, there are no specific biochemical or radiological investigations that can conclusively diagnose this phenomenon [2].

The significance of pancreatic heterotopia of the gallbladder is that this rare histological finding may account for atypical symptoms of biliary colic, because of possible acute or chronic pancreatitis of this ectopic tissue [3, 6]. Sato et al. [3] demonstrated the exocrine function of heterotopic pancreatic tissue, which supports the suggestion of the possibility of pancreatitis of this tissue. It is possible that the exocrine and endocrine function of pancreas tissue could lead to inflammation and irritation of surrounding tissues, which are not usually exposed to the secretion of these enzymes and hormones, which could lead to acalculous cholecystitis [3].

It is also important to consider the risk of malignant transformation of heterotopic pancreatic tissue, although the likelihood of this is rare [4]. In addition to the potential for malignant transformation of heterotopic tissue, it has also been suggested that the elevation of pancreatic enzymes within bile could damage the biliary tract and thus increase the risk of development of gallbladder cancer [3].

The atypical presentation of biliary colic in this patient could be explained by the rare histological finding of pancreatic heterotopia of the gallbladder.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

FUNDING

None.

CONSENT

Signed informed consent was obtained from the patient prior to writing this case report.