-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Marie Nyssen, Camille Marliere, Didier Fobe, Konstantinos Kothonidis, Vermiform appendix torsion complicated by postoperative venous pylephlebitis: a case report and review of literature, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2023, Issue 5, May 2023, rjad314, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjad314

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Vermiform appendix torsion is a rare condition that mimics acute appendicitis and is diagnosed during surgery. On the other hand, pylephlebitis (or septic thrombophlebitis) is a complication that occurs due to occlusive thrombosis of mesenteric venous system branches secondary to intra-abdominal infections. Although rare since the antibiotic era, it must be considered in the differential diagnosis of postoperative fever. We report the case of a 63-year-old man who was diagnosed with acute appendicitis. During laparoscopy, an anti-clockwise vermiform appendix torsion (360°) was identified. On postoperative day 3, the patient developed recurrent pyrexia related to ileocolic vein pylephlebitis, requiring specific management. Vermiform appendix torsion is a rare condition that is indistinguishable from acute appendicitis until an appendicectomy is performed. Whereas previous studies have reported an uneventful postoperative period in cases of vermiform appendix torsion, we present the first case of pylephlebitis as a rare complication and discuss adequate treatment.

INTRODUCTION

Vermiform appendix torsion is a rare condition that affects both paediatric and adult populations [1]. Clinical presentation and radiologic images mimic acute appendicitis, with an indistinguishable diagnosis until an appendicectomy is performed. Primary (anatomic) and secondary (mass effect) causes are recognized in appendix torsion, which is most frequently twisted in the anti-clockwise direction, from 180° to 1080° [2, 3].

However, pylephlebitis has been a rare complication (<1% of intra-abdominal infections) since the antibiotic era. It affects the mesenteric venous system secondary to intra-abdominal infections and, most frequently, diverticulitis. Morbidity and mortality are high rates due to late diagnosis and severe complications [4, 5].

We describe the 35th case of vermiform appendix torsion in adult population and the first complicated with pylephlebitis.

CASE REPORT

We report the case of a 63-year-old man who presented to the emergency room with pain in the right iliac fossa (RIF) for 12 h. Pain was localized, constant and associated with vomiting and pyrexia (38°C). Clinical examination revealed significant tenderness in the RIF, with positive MacBurney signs.

Laboratory findings were an increased C-reactive protein of 49.9 mg/l (normal range 0–5 mg/l) and neutrophilic hyperleukocytosis of 10.29 × 103/μl (normal range 1.4–7.7 × 103/μl). Blood cultures were performed.

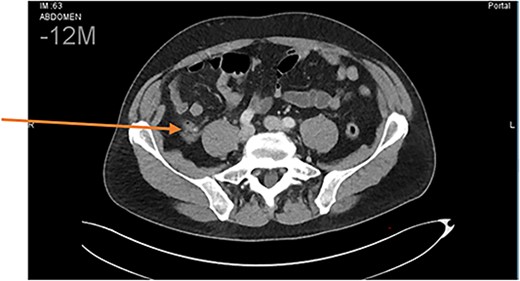

Abdominal computed tomography findings were compatible with uncomplicated acute appendicitis (Fig. 1).

Abdominal CT scan. Diagnosis of uncomplicated acute appendicitis.

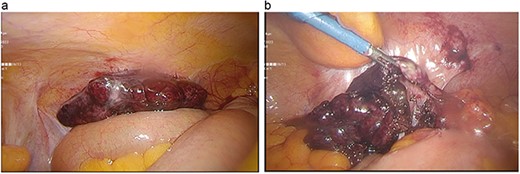

During laparoscopy, we found a necrotic-haemorrhagic vermiform appendix, with an anti-clockwise rotation of 360°, 0.5 cm from its base (Fig. 2a and b).

(a) Appendix with 360° anti-clockwise torsion. (b) Detwisted appendix with necrotic-haemorrhagic appearance.

The appendix was carefully untwisted. The meso-appendicular tissue was dissected with artery coagulation. The appendiceal base was normal, and an appendicectomy with two double-ligation stitches was performed. Postoperative intravenous antibiotics (amoxicillin and clavulanic acid) were prescribed.

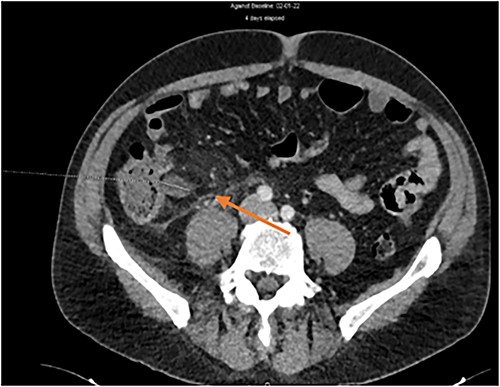

In total, 24 h later, the laboratory confirmed positive admission blood cultures (8/8 samples) for multi-sensitive Escherichia coli and Enterococcus faecalis. On postoperative day 3, despite appendicectomy and appropriate antibiotics, the patient presented with recurrent pyrexia (>38°C) and pain in the RIF. Therefore, a second abdominal scanner was performed and identified a thrombosis of the ileocolic vein associated with significant peripheral fat inflammation (Fig. 3).

The blood cultures were repeated. Because of endovascular infection, amoxicillin-clavulanic acid was discontinued and targeted antibiotic therapy was switched to ceftriaxone with amoxicillin and metronidazole. Finally, as the new blood cultures were positive for both multi-sensitive E. coli and extended-spectrum-beta-lactamase E. coli, a second switch with piperacillin and tazobactam was initiated. The treatment was prolonged for a total of 4 weeks from the first negative blood cultures (postoperative day 4). Anticoagulation was not administered in this case because of the small size of the phlebitis, the rapidly favourable clinical and biological evolution and the absence of liver complications. Subsequently, the evolution remained favourable.

The anatomopathological analysis confirmed a transmural haemorrhage with mucosal necrosis without signs of malignancy, compatible with vermiform appendix torsion. Macroscopic examination revealed the presence of a faecalith, probably responsible for the torsion.

DISCUSSION

Vermiform appendix torsion is a rare condition that was first described in 1918 [6]. According to a review of the English literature, 59 cases were described from 1918 to 2018 [7], with 33 cases in the adult population and 26 in children [1, 7–9]. One case in 2008 described torsion with a faecalith, which was also the oldest patient [3].

Its clinical presentation mimics appendicitis and is indistinguishable until surgical treatment has been performed. Radiology is often not helpful for the diagnosis, although some authors have described ultrasound (USS) images with a ‘target sign’ corresponding to the torsion zone. This can be due to primary or secondary causes and is often twisted anti-clockwise from 180° to 1080°. Torsion leads to lumen obstruction that compromises the lymphatic and venous return and arterial supply, resulting in haemorrhagic infarction and a consequent inflammatory response. In primary torsion, a necrotic-haemorrhagic appendix is found, without an evident intra-luminal lesion [2]. Anatomical findings included a long, fan-shaped mesoappendix with a narrow base and pelvic position. Excessive bowel movements may also be a contributing factor. Secondary torsion is associated with a mass effect linked to mucocele, cystadenoma, lipoma, faecalith, etc. [3]. Treatment is appendicectomy.

Postoperative fever commonly occurs in patients who undergo surgery. The differential diagnosis depends on timing of the onset of fever [10]. In our case, fever was considered in the early postoperative period (between days 0 and 3), and differential diagnosis included systemic infection, stress- or immune-mediated inflammation, early surgical site infection predating infection and non-infectious causes such as thromboembolism and toxicosis.

Pylephlebitis is a suppurative thrombosis affecting the mesenteric venous system secondary to intra-abdominal infections. It begins in the small veins, drains the area of infection, and can spread into the largest vessels until the portal vein. Diverticulitis is the most common source of infection.

Although rare since the antibiotic era, it is still associated with high morbidity and mortality due to delayed diagnosis and severe complications (hepatic abscess, mesenteric infarction, etc.) [4, 5, 11]. Symptoms are non-specific (like fever, abdominal pain, jaundice, etc.) and depend on intra-abdominal sources of the infection. Blood cultures are not systematically positive, range from 40% to 80%, and are often polymicrobial [12–14].

The diagnosis is made radiographically, on an abdominal computed tomography portal phase scan or Doppler ultrasonography. Treatment involves the use of appropriate antibiotics selected according to the endovascular activity, bacteriological results and abdominal flora. Gram-negative aerobes, anaerobes and Streptococcus species are amongst the most frequently isolated pathogens. The recommended duration of antibiotic therapy ranges from 4 to 6 weeks, with some authors advocating for intravenous administration until a significant clinical response is observed. Anticoagulation is controversial. There are currently no significant results. Comparative studies have reported reduced portal hypertension and faster thrombosis deterioration in patients receiving anticoagulation therapy [12, 15]. Portal vein involvement and known coagulation disorders could be indications without clearly established guidelines. However, there was no significant difference in the mortality rate.

CONCLUSION

Vermiform appendix torsion is a rare condition that mimics appendicitis. This could be due to secondary causes, including faecalith, which has only been described once in the literature. The postoperative period was usually uneventful. Although rare, pylephlebitis should be included in the differential diagnosis if symptoms persist after surgical treatment.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

FUNDING

None.