-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Ryohei Ushioda, Tomonori Shirasaka, Dit Yoongtong, Boonsap Sakboon, Jaroen Cheewinmethasiri, Hiroyuki Kamiya, Nuttapon Arayawudhikul, Coronary reoperation with a free internal mammary artery connected to the right coronary artery as an inflow site; a coronary-to-coronary bypass, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2023, Issue 4, April 2023, rjad136, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjad136

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Second-time coronary artery bypass grafting is sometimes technically challenging due to severe adhesion of the heart, difficulty of identifying target coronary arteries, advanced sclerosis of the ascending aorta and limited availability of graft vessels. Here we report a patient, in whom a coronary-to-coronary bypass grafting from the native right coronary artery to the left anterior descending artery using a free right internal mammary artery was used as a graft conduit.

INTRODUCTION

Second-time coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) is sometimes technically challenging due to severe heart adhesion, difficulty identifying target coronary arteries, advanced sclerosis of the ascending aorta and limited availability of graft vessels [1, 2]. Herein, we report a case of second-time CABG with a free right internal mammary artery (IMA) from the native right coronary artery to the left anterior descending artery (LAD).

CASE PRESENTATION

A 67-year-old male underwent on-pump beating CABG 9 years ago due to unstable angina associated with three-vessel coronary artery disease with preserved left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) of 62%. In-situ left IMA, left radial artery (RA), and pedicled saphenous vein graft (SVG) were used to revascularize the LAD, obtuse marginal coronary branch (OM) and endarterectomies posterior descending coronary artery, respectively. He was admitted to our institution again with chest pain and dyspnea 4 years after the first operation.

Comorbidities include hypertension, dyslipidemia, varicose vein, history of upper gastrointestinal tract bleeding from Mallory–Weiss Syndrome, cerebrovascular accident from lacunar infarction with episodic transient ischemic attacks and post-spinal surgery, both in cervical and lumbar level due to spinal canal stenosis were evident. The echocardiogram showed it preserved LVEF of 52%, and coronary angiography demonstrated only patent left RA conduit. The remaining SVG was not available as they were thrombosed and varicose. The right gastroepiploic artery was not suitable, considering Mallory–Weiss syndrome history. Moreover, the ascending aorta was severely affected by atherothrombotic pathology detected by preoperative computed tomography. Therefore, the option of usage of the free graft with proximal anastomosis on the ascending aorta seemed dangerous. For this reason, the operative plan was one single bypass grafting with in-situ right IMA (RIMA) to the LAD.

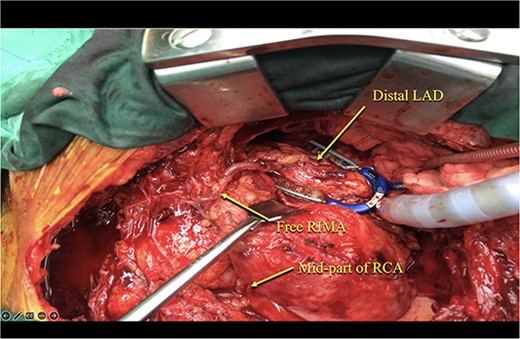

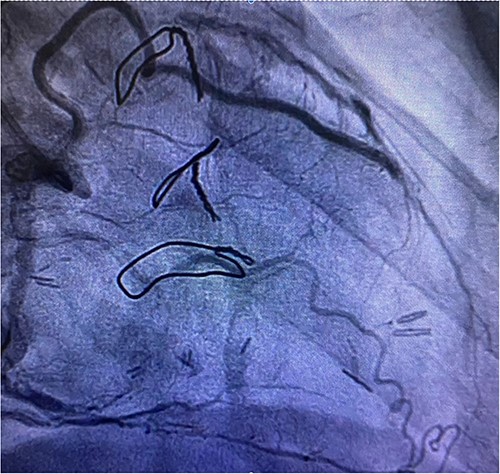

Before resternotomy, a cardiopulmonary bypass was performed via the right common femoral artery and vein. The RIMA was harvested in a semi-skeletonized fashion because skeletonized IMA is in general, longer than pedicled IMA. However, the RIMA could not reach the LAD in the present case due to cardiomegaly. Therefore, the proximal end of the RIMA was cut to use as a free graft. Subsequently, the proximal portion of the patent RA graft was tried to dissect as a proximal anastomosis site, but it was not possible due to severe adhesion of the surrounding tissue. Therefore, we decided to anastomose the proximal RIMA to the proximal right coronary artery (RCA) as the inflow site. The distal RIMA was anastomosed to the LAD as usual (Fig. 1). The postoperative course was uneventful, and the patient was discharged 11 days after the operation. A 3-month postoperative coronary angiogram showed the patency of the RA and RIMA conduits (Fig. 2). Moreover, from coronary computed tomography angiography after 6 years, it was confirmed that it was still patent (Fig. 3).

The free RIMA was anastomosed to the mid-part of RCA and bypassed to the distal LAD.

Post redoing coronary angiography showing patency of RIMA to LAD after 3 months.

Cardiac computed tomography showing patency of RIMA to LAD 6 years after redoing CABG operation.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

The number of patients who have undergone CABG has increased; subsequently, CABG reoperation has increased [3]. However, the number of graft designs and choice of inflow site is limited when performing re-operative CABG [4, 5]. In the present case, only RIMA was available as a graft but could not be used as an in-situ graft due to insufficient length. Therefore, a coronary-to-coronary bypass grafting using a free RIMA graft was performed as an ultimate option.

For redo CABG, it is my strategy to do it beating heart (off-pump first or second on-pump beating) as a default procedure. Although, if I have to do an arrested heart, I will still not touch or occlude any previous grafts but focus on the coronary target that needs re-revascularization. The inflow can be either pedicled RIMA, right gastroepiploic artery or SVG (from an innominate artery, descending aorta).

That’s why coronary arteries are often affected by atherosclerotic changes in patients undergoing CABG, a coronary-to-coronary bypass grafting is not a viable option. However, there have been several previous reports, and the first one was made by Rowland and Grooters in 1987, to the best of our knowledge [6]. They reported two cases; one patient received CABG from the RCA to the LAD and OM using a saphenous vein because the ascending aorta was severely calcified, and the other patient received CABG from the first diagonal to the second diagonal and the OM artery using bifurcated SVG [6]. Since then, there have been ⁓40 reports on ‘coronary-to-coronary’ or ‘coronary-coronary’ bypass, which can be seen in PubMed. Together with our present case, coronary-to-coronary bypass grafting can be an alternative for patients having no other options.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

FUNDING

None.

DATA AVAILABILITY

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.