-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Divya Naresh, Bushra Othman, Matthew Yuan-Kun Wei, Vinna An, An unwelcome guest: two cases of colonic metastatic lobular breast cancer, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2023, Issue 3, March 2023, rjad160, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjad160

Close - Share Icon Share

ABSTRACT

Metastatic spread of invasive lobular breast cancer is rare. It can have a delayed and varied presentation that can mimic other bowel pathologies, such as colorectal cancer and inflammatory bowel disease, making its diagnosis difficult. In this study, we present two patients who required colonic resection due to malignant obstruction caused by metastatic invasive lobular carcinoma of the breast.

INTRODUCTION

Invasive lobular carcinoma (ILC) of the breast accounts for 10% of all breast cancers, with distinct characteristics in terms of tumor biology, clinical presentation and prognostic implications compared to other types of breast cancer [1]. Common sites of invasive ductal carcinoma (IDC) metastases include lungs, bones and liver, yet ILC has a less predictable pattern of metastatic spread. The latter can manifest in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract (stomach, small bowel and colon) as well as in the ovary and peritoneum [2–4]. ILC is more responsive to medical therapy compared to IDC, but with comparable overall survival [3].

We present two patients who required colonic resection due to obstruction secondary to metastatic ILC.

CASE 1

A 72-year-old female presented with abdominal pain and loss of weight. Computed tomography (CT) imaging demonstrated caecal and ascending colon thickening (Fig. 1a). Colonoscopy showed abnormal mucosa in the ascending colon that was unable to be traversed endoscopically (Fig. 2a) and slightly irregular mucosa at the hepatic flexure (Fig. 2b). The appearances were not typical of either a primary colon malignancy or a stricture secondary to inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Biopsies were non-diagnostic, only showing mucosa with features of regeneration and repair. Given the patient was symptomatic, a laparoscopic right hemicolectomy was performed. Intraoperatively, a thickened firm ascending colon was seen suggesting possible submucosal involvement. Firm nodules were found in the terminal ileum mesentery and proximal transverse colon.

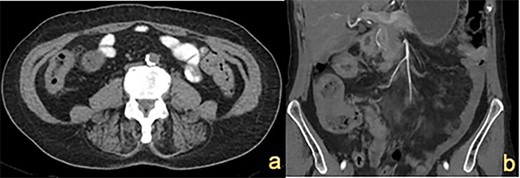

CT abdomen showing (a) thickened ascending colon wall and (b) thickened caecum and transverse colon (indicated by white arrows).

Colonoscopy demonstrating (a) ascending colon lesion, (b) hepatic flexure mucosal abnormality and (c) cobblestoned mucosa in the transverse colon.

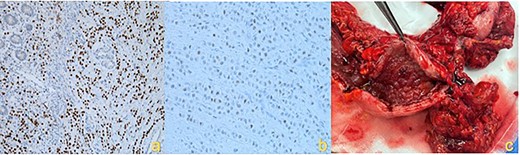

Histopathology confirmed metastatic ILC with immunohistochemistry (IHC) positive for CK7, GATA3, GCDFP-15 and ER but negative for PR and HER2 (Fig. 3a and b). Postoperative mammogram and ultrasound showed no obvious breast lesion, but suspicious left axillary lymphadenopathy. Following her recovery, the patient received adjuvant endocrine and targeted biological treatment in the form of letrozole and Palbociclib, respectively.

IHC staining showing (a) Gata3 positive cells, (b) ER positive cells and (c) macroscopic hemicolectomy specimen with diffuse infiltrative ILC.

CASE 2

A 70-year-old female presented with altered bowel habits. Relevant history included previous right-sided ILC 7 years prior, treated with wide local excision, sentinel node biopsy and adjuvant radiotherapy. There were no signs of recurrence on surveillance imaging. Fecal calprotectin and inflammatory markers were normal.

CT imaging showed a thickening in the right colon (Fig. 1b). Colonoscopy revealed a stricturing lesion in the hepatic flexure, with abnormal cobblestone-type mucosa without ulcerations or erosions, which transitioned to normal mucosa near the splenic flexure (Fig. 2c). Endoscopic appearances could have represented Crohn’s disease given the cobblestoning but appeared atypical. Biopsies were unable to prove malignancy or IBD but demonstrated fibrosis with features of prolapse or healed ischaemic damage. There were no oestrogen-positive cells.

The patient underwent an extended right hemicolectomy (Fig. 3c). Histopathology confirmed diffuse infiltration by metastatic ILC with multifocal lymphatic and perineural invasion. The tumor was strongly HER2 positive, weakly ER positive (10%) and PR negative. The patient proceeded to palliative paclitaxel chemotherapy. Unfortunately, the patient had rapid disease progression and was eventually transitioned to comfort care measures.

DISCUSSION

Breast cancer metastases to the GI tract are rare. However, ILC has a predilection to spread to the GI tract in 5% of cases, compared to 0.2% in IDC [5]. The most common site of GI spread is the stomach, followed by the small bowel and colorectum. Although not entirely clarified, it is thought that the loss of E-cadherin in ILC (responsible for inter-cellular adhesion), combined with a more favorable micro-environment in the peritoneum for ILC cells contributes to this predilection [3].

Colonic metastatic ILC can be difficult to diagnose and recognize. Patients can be asymptomatic, present with non-specific abdominal symptoms or emergently with obstruction, bleeding or perforation [6]. The interval between the primary ILC and metastatic recurrence is often long, with a median of 6–7 years, and some reports of up to 25 years [7]. Furthermore, as we have demonstrated with Case 1, GI metastatic disease can also be the first indication of previously undiagnosed ILC.

Colonic metastatic ILC often mimics other pathology in radiological and endoscopic investigations, namely primary colonic malignancy or IBD. On cross-sectional imaging, these lesions can appear as a diffuse mural thickening, with or without circumferential stenosis [7]. The endoscopic appearance is characterized by a multi-nodular cobblestone-like appearance of the mucosa, as shown in our report [8].

However, endoscopy can be insufficient in providing an accurate diagnosis due to the submucosal nature of infiltration and lack of mucosal lesions [7]. Therefore, clinical suspicion for metastatic ILC to the colon should be present in female patients with atypical colon mucosa on endoscopy that does not correlate with histopathology, particularly in those with a history of ILC. On IHC staining, ILC will usually be positive for CK7, GCDFP-15 and ER, as demonstrated in our case. Overexpression of HER2 can also be present. Stains normally associated with primary GI malignancies, such as CK20 and CEA, will be negative [9].

CONCLUSION

Colonic metastatic ILC is rare. It can be difficult to diagnose due to the varied presentation, the long natural history of ILC metastatic relapse and a tendency to mimic other disease processes. Given these challenges, it is important to maintain a high level of clinical suspicion in patients with a relevant history to ensure prompt investigation and appropriate treatment.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

FUNDING

None.

INFORMED CONSENT

Informed consent has been obtained from both patients.