-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Lauren Wallace, Ya’acov Leigh, Pneumomediastinum and pneumothorax: a rare complication of laparoscopic total extraperitoneal inguinal hernia repair, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2023, Issue 3, March 2023, rjad146, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjad146

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Increasing utilization of a laparoscopic total extraperitoneal (TEP) approach for inguinal hernia repairs has led to rare complications. We describe a rare case of subcutaneous emphysema, pneumomediastinum and pneumothorax following a laparoscopic TEP inguinal hernia repair in a 29-year-old male. Mechanisms posited include extraperitoneal carbon dioxide migration via the retroperitoneal space and dissection along the fascia transversalis and endothoracic fascia anteriorly to enter the mediastinum. Intra-operatively the patient coughed vigorously, potentially propagating the extent of extraperitoneal gas dissection and exacerbating these complications. Given the potential morbidity, it is important for surgeons and anaesthetists to recognize these complications.

INTRODUCTION

A laparoscopic total extraperitoneal (TEP) approach is increasingly used for inguinal hernia repair [1]. Subcutaneous emphysema, pneumomediastinum and pneumothoraces are extremely rare complications of TEP repair and are most often associated with inadvertent pneumoperitoneum [1, 2]. There are limited case reports of these complications after TEP repair without peritoneal breach. We discuss a rare case of subcutaneous emphysema, pneumomediastinum and a pneumothorax due to extraperitoneal gas insufflation during a laparoscopic TEP inguinal hernia repair.

CASE REPORT

A 29-year-old male presented for an elective left TEP inguinal hernia repair. His past medical history was unremarkable. Induction and tracheal intubation were uneventful. A 10 mm periumbilical port was placed into the preperitoneal space which was defined with blunt dissection and insufflated with carbon dioxide (CO2) at a pressure of 12–15 mmHg. Two 5 mm infraumbilical midline ports were placed into the preperitoneal space under vision. Shortly after the second port placement, the patient began to move, contracting his abdominal wall and coughing vigorously. The anaesthetist was alerted, rocuronium administered and adequate paralysis achieved. Oxygen saturations remained normal with no respiratory distress or anaesthetic concerns. There were no intra-operative complications or overt peritoneal breach.

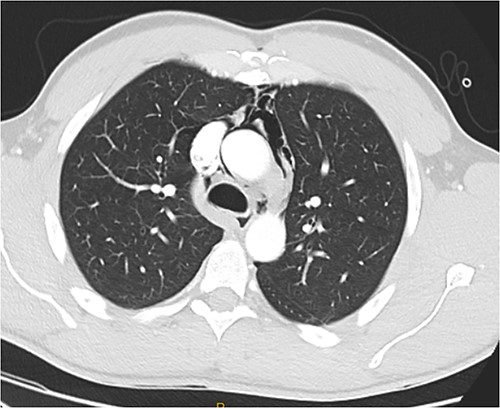

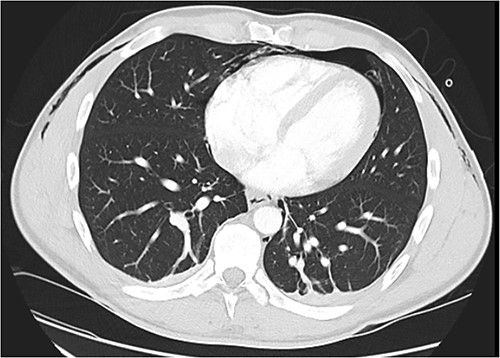

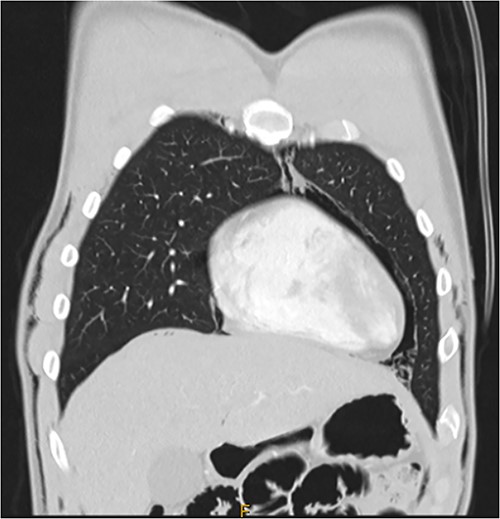

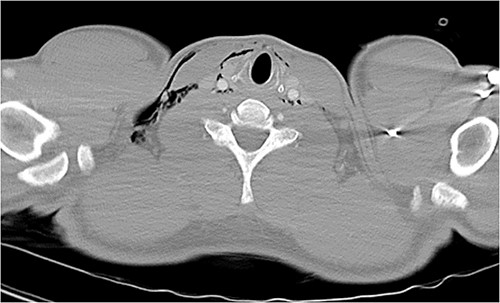

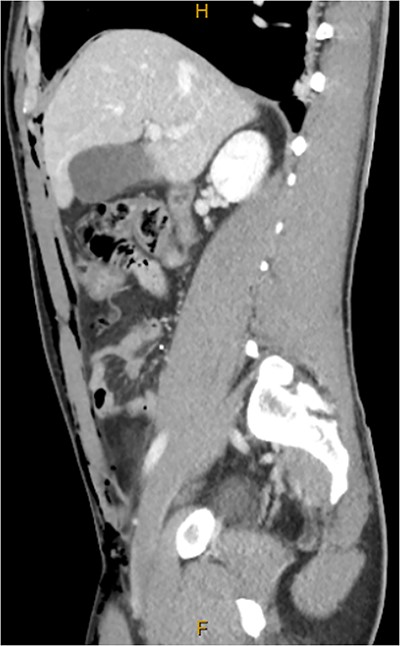

Following extubation, bilateral chest wall subcutaneous emphysema was noted extending to the neck. He also complained of central chest discomfort, without respiratory distress, oxygen desaturation or airway obstruction. Chest X-ray (CXR) revealed pneumomediastinum and surgical emphysema in the lateral chest walls bilaterally. Computed tomography (CT) of the chest, abdomen and pelvis demonstrated large volume subcutaneous emphysema bilaterally in the scrotum, abdominal and chest walls extending to the neck (see Figs 2–5). Gas was noted between the abdominal muscle layers, extraperitoneal and retroperitoneal spaces without pneumoperitoneum (see Figs 5–6). Moderate pneumomediastinum was prominent within the superior and antero-inferior mediastinum without evidence of tracheal or oesophageal injury and an associated small left pneumothorax was noted (see Figs 1–3).

CT chest axial, small left pneumothorax and chest wall subcutaneous emphysema.

CT chest coronal, pneumomediastinum and bilateral subcutaneous emphysema.

CT chest and neck axial, subcutaneous emphysema extending to neck.

CT abdomen and pelvis sagittal, abdominal wall subcutaneous emphysema with gas between muscle layers.

CT abdomen and pelvis axial, left retroperitoneal gas locules overlying iliopsoas muscle.

He was given oral analgesia and supplemental oxygen. A left-sided 24-French gauge intercostal catheter (ICC) was inserted to facilitate air transfer to a tertiary centre. He remained clinically well, and the ICC was removed after 2 days. No recurrence of the pneumothorax was demonstrated on repeat CXR and he was discharged 4 days post-operatively.

DISCUSSION

Improved post-operative recovery, with decreased pain, greater patient satisfaction and more rapid return to daily activities, has resulted in increasing preference for laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair [3, 4]. Given the increasing use of this technique, it is important for surgeons and anaesthetists to be aware of rare complications including subcutaneous emphysema, pneumomediastinum and pneumothorax [1].

Pneumomediastinum is a known complication of laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair, thought to be due to air tracking from a pneumoperitoneum, either as part of a transabdominal pre-peritoneal (TAPP) approach or accidental peritoneal breach during laparoscopic TEP repair [1, 2, 5]. CO2 may traverse from the abdominal to thoracic cavity through the aortic and oesophageal hiatuses, pleuroperitoneal hiatus or Bochdalek’s foramen, congenital diaphragmatic defects or inadvertent falciform ligament injury [1, 2, 6].

A limited number of cases of pneumomediastinum and pneumothoraces after TEP inguinal hernia repair without peritoneal breach have been reported [1–4, 7–9]. A proposed route of extraperitoneal gas tracking into the mediastinum includes entry into the retroperitoneal space, along tissue planes through diaphragmatic openings to enter the mediastinum, pleural space and neck [2, 4, 8–10]. In this case, gas locules were demonstrated in the extraperitoneal and retroperitoneal spaces without pneumoperitoneum, supporting this route of CO2 dissection. Additionally, the fascia transversalis is continuous with the endothoracic fascia of the thorax, allowing extraperitoneal gas to dissect through fascial planes and into the mediastinum via anterior diaphragmatic gaps, providing another route of tracking [1, 2, 10, 11]. In this case, the extent of preperitoneal dissection and anterior mediastinal gas seen on CT suggests this route likely also contributed to the pneumomediastinum and pneumothorax.

Increased risk of these complications has been associated with a prolonged extraperitoneal insufflation time, often defined as greater than 2 hours [1, 7, 8]. Additionally, increased insufflation pressures have been posited to promote more extensive fascial CO2 dissection [1, 7, 8]. Some advocate for pressures <15 mmHg to minimize these complications [3, 8], while others suggest using <10 mmHg [9]. However, limited available data leave these recommended parameters unclear. While the current case had higher insufflation pressures than those suggested by some, this was a standard practice at our institution without previous similar events. It may have contributed to fascial dissection by CO2 as previously described, with the intra-operative abdominal muscle contraction and coughing further increasing pressure within the space and propagating more extensive CO2 tracking through these planes cranially into the mediastinum and neck.

Other non-operative aetiologies of pneumothorax and pneumomediastinum should be considered. These include iatrogenic tracheal injury, barotrauma, pulmonary bullae or bleb rupture or spontaneous pneumothorax, particularly in young thin men who are at increased risk [3, 4, 6, 8, 9]. While it is possible this was a primary event or related to anaesthesia, it is thought very unlikely given the relatively small size of the pneumothorax and extensive pneumomediastinum and subcutaneous emphysema in the abdominal and chest walls. Additionally, there was no radiologically or clinical evidence of tracheal perforation. More likely, it resulted from the extraperitoneal insufflation of the TEP repair via mechanisms previously described.

Most pneumomediastinum and pneumothoraces after TEP inguinal hernia repairs are managed conservatively with supplemental oxygen and observation, with only few requiring ICC insertion [1, 8]. However, given the potential for significant morbidity, it is an important complication that both surgeons and anaesthetists should recognize. Minimizing insufflation time and pressures may reduce the risk of these complications, however specific limits remain unclear [1, 8]. This case highlights the potential for increases in abdominal pressure intra-operatively to exacerbate fascial CO2 dissection and worsen subcutaneous emphysema and mediastinal gas migration. In the event of this, a high clinical suspicion is essential and should prompt close monitoring including chest auscultation, palpation for subcutaneous emphysema and observing for signs of respiratory distress. Increasing use of laparoscopic inguinal hernia repairs will likely lead to an increased incidence of these complications. As such, further research is required to characterize risk factors for these complications.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.

FUNDING

No funding source for this article.