-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Valentin Butnari, Ahmer Mansuri, Sandeep Kaul, Veeranna Shatkar, Richard Boulton, Radiofrequency thermocoagulation of haemorrhoids: learning curve of a novel approach, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2023, Issue 3, March 2023, rjad115, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjad115

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Haemorrhoidal disease (HD) is a common condition that often requires surgical treatment. In comparison with other traditional techniques, radiofrequency thermocoagulation (RFTC) has multiple advantages to traditional repairs and can be a good alternative in surgical management of HD. We retrospectively analysed 20 patients with Grades 2 (n = 6, 30%) and 3 (n = 12, 70%) haemorrhoids undergoing RFTC from 1 September 2019 to 31 December 2021. Outcomes including post-operative (PO) pain, immediate/late PO complications, recurrence and patient satisfaction were assessed. Twenty cases were included in this case series. All pathological symptoms showed significant improvement in PO period. Eight complications were noted, including minor bleeding (n = 2), bleeding that required admissions (n = 3), pain (n = 2) and recurrence (n = 1). The mean time off work is 7 days and all patients were satisfied or very satisfied PO as per telephone questionnaire. RFTC is a safe and effective solution in the management of HD and is a good alternative to conventional procedures.

INTRODUCTION

Haemorrhoidal disease (HD) is one of the most common anorectal conditions. The main symptoms are per-rectal bleeding, pain, itching and discharge [1]. Multiple surgical options are available for different grades of HD in order to relieve patient symptoms and restore normal anorectal anatomy. Depending on the degree of haemorrhoids and the severity of the symptoms the surgeon will choose between following surgical methods of treatment: injection sclerotherapy, rubber band ligation (RBL), infrared ablation, cryoablation, monopolar, bipolar or laser surgery. For first- and second-degree haemorrhoids, evidence suggests that RBL is as effective as haemorrhoidectomy [2]. However, for large second- or third-degree haemorrhoids, more invasive techniques such as Milligan Morgan haemorrhoidectomy are more effective in minimising recurrence although post-operative (PO) pain and prolonged recovery time are common complications [3]. Despite the presence of numerous non-surgical therapies for haemorrhoids, none of the procedures mentioned previously have established its superiority over the rest. The optimal procedure remains under debate, but newer less invasive techniques such as radiofrequency thermocoagulation (RFTC) are gaining in popularity because of less pain, the possibility the procedure being performed under local anaesthesia and an earlier return to normal activities. Ideally, a method that could return the anal cushions to their normal size and positions would be a natural preference to the one that destroys tissue and may interfere with the mechanism of continence. RFTC is found to meet these preferences [4].

This single-centre prospectively maintained database examines outcomes from RFTC surgery for HD undertaken at a district general hospital in London. We are assessing the safety, efficacy and outcomes of new approach.

CASE SERIES

Participants

This study was conducted at the Barking, Havering and Redbridge University Hospitals NHS Trust (BHRUT). Parameters of effectiveness and comfort were investigated for patients who underwent RTFC between September 2019 and December 2021. Data were analysed from a prospectively maintained database using electronic healthcare records, clinical notes and telephone interviews. Identified data included patient demographics such as age at the time of surgery, gender and American Society for Anaesthesiology (ASA) grading. Specific surgical data were identified, such as HD grade, power, duration of treatment with radiofrequency and complications. Both procedures were conducted by three colorectal surgeons with extensive experience in the surgical treatment of HD. Data were collected independently by two assessors and were cross-checked for accuracy. Patients having associated anal fissure, HD grade 4, anal spasm or infective anal pathologies like cryptitis or proctitis were excluded from the study. The end of follow-up was 1 June 2022.

Principle of RFTC

The radiofrequency unit generates a very high frequency radio wave of 4 MHz to generate heat at the tip of the probe. The heat causes the intracellular water to boil, and thereby increases the cell inner pressure, to the point of breaking it from inside to outside. This phenomenon is described as cellular volatilisation, leading to coagulative necrosis of tissue [5]. Long term, in HD, this achieves plication of anorectal mucosa and improved symptoms [6].

RFTC procedure

Our surgical procedure was divided into 10 steps:

Consent and anaesthesia.

All patients from our study were operated on under general anaesthesia because of their preference but this procedure can be easily done under local anaesthetic, with or without sedation.

2. Lithotomy position.

3. Local anaesthetic.

The local anaesthetic was injected into ischiorectal fat immediately peripheral to the external sphincter with total of 20 ml of 0.5% bupivacaine with or without adrenaline (1/200 000).

4. Proctoscope insertion.

5. Fluid barrier creation.

An injection of between 1 and 3 ml of NaCl 0.9% between submucosa affected by HD and the internal anal sphincter.

6. RFTC.

A special probe with 4 MHz frequency was introduced into affected tissue and a continuous radiofrequency ablation was used to coagulate the haemorrhoid. The ablation was continued until the tissue exhibited whitish discolouration, after which the energy was applied to the external surface of the haemorrhoidal tissue to optimise tissue desiccation. A maximum of 3000 MHz with a power sitting of 25 W was applied to an individual haemorrhoidal tissue at one time [7]. After the removal of the probe, we can observe the return of anal cushion to the normal size.

7. Application of swab with cold saline.

8. Achievement of definitive haemostasis.

9. Anal pack made from collagen inserted into anal canal.

This pack was removed a few hours later or upon urge for defecation.

10. All patients were discharged on the same day with routine analgesia.

Outcomes

The primary outcome of the study was to assess the pain index in the first 7 days post-procedure, to detect of changes in haemorrhoid symptoms and to record time off work because of recovery after RFTC surgery. Secondary outcomes of the study included measuring complication rates, recurrence and patient satisfaction post procedure. Patients were followed up for 6 months following the operation.

The overall pain index in first 7 days post-procedure is defined in this study as intensity and duration of pain based on visual analogue scale. Time off work is defined as total period taken to return to usual activity of domestic and social life. Short-term complications from surgery were extracted from all correspondence within 30 days post-surgery and graded as: minor bleeding, major bleeding, severe pain, urinary retention, infection, anal stenosis and recurrence. Patient satisfaction is defined as telephone questionnaire (The Short Assessment of Patient Satisfaction (SAPS)) [8].

Patient characteristics

All 20 patients who underwent RFTC at BHRUT over a 3-year interval were included in this study (Table 1). There was a predominance of male patients in the cohort (n = 11, 55%) relative to female. Patient median age was 59 years (range: 35–87). The majority of patients had an ASA score of 3 (n = 70%). There were six (30%) cases of Grade 2 HD and 12 (70%) cases of Grade 3 HD. For 45% (n = 9) of cases, RBL was not successful. Six cases (25%) were managed conservatively and remaining three (15%) patients underwent combined methods of treatment.

| . | RFTC . | |

|---|---|---|

| n . | % . | |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 9 | 45 |

| Male | 11 | 55 |

| Age at the time of surgery (years) | ||

| 18–60 | 10 | 50 |

| 61–70 | 4 | 20 |

| >70 | 6 | 30 |

| Haemorrhoidal severity | ||

| Grade 2 | 6 | 30 |

| Grade 3 | 12 | 70 |

| Prior treatment | ||

| Conservative | 6 | 30 |

| Phenol injection | 2 | 10 |

| RBL | 8 | 40 |

| THD | 0 | |

| Combined methods | 4 | 20 |

| . | RFTC . | |

|---|---|---|

| n . | % . | |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 9 | 45 |

| Male | 11 | 55 |

| Age at the time of surgery (years) | ||

| 18–60 | 10 | 50 |

| 61–70 | 4 | 20 |

| >70 | 6 | 30 |

| Haemorrhoidal severity | ||

| Grade 2 | 6 | 30 |

| Grade 3 | 12 | 70 |

| Prior treatment | ||

| Conservative | 6 | 30 |

| Phenol injection | 2 | 10 |

| RBL | 8 | 40 |

| THD | 0 | |

| Combined methods | 4 | 20 |

| . | RFTC . | |

|---|---|---|

| n . | % . | |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 9 | 45 |

| Male | 11 | 55 |

| Age at the time of surgery (years) | ||

| 18–60 | 10 | 50 |

| 61–70 | 4 | 20 |

| >70 | 6 | 30 |

| Haemorrhoidal severity | ||

| Grade 2 | 6 | 30 |

| Grade 3 | 12 | 70 |

| Prior treatment | ||

| Conservative | 6 | 30 |

| Phenol injection | 2 | 10 |

| RBL | 8 | 40 |

| THD | 0 | |

| Combined methods | 4 | 20 |

| . | RFTC . | |

|---|---|---|

| n . | % . | |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 9 | 45 |

| Male | 11 | 55 |

| Age at the time of surgery (years) | ||

| 18–60 | 10 | 50 |

| 61–70 | 4 | 20 |

| >70 | 6 | 30 |

| Haemorrhoidal severity | ||

| Grade 2 | 6 | 30 |

| Grade 3 | 12 | 70 |

| Prior treatment | ||

| Conservative | 6 | 30 |

| Phenol injection | 2 | 10 |

| RBL | 8 | 40 |

| THD | 0 | |

| Combined methods | 4 | 20 |

Haemorrhoid severity score [9]

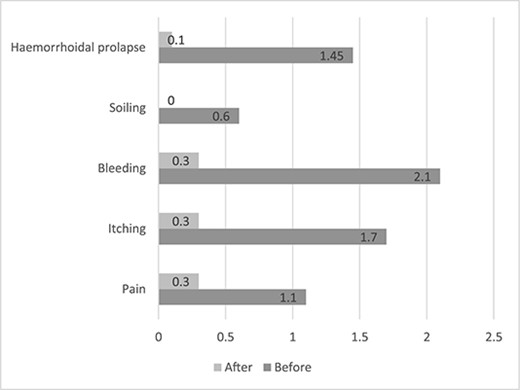

The severity of haemorrhoidal symptoms was assessed 3 weeks before and 2–3 months after procedure during follow-up clinic appointment. The total score for each patient was calculated. A significant improvement in the total haemorrhoid severity score (HSS) score can be seen, with a mean score of 7 before surgery and a mean score of 1.05 afterward. The individual score for every symptom is demonstrated (Table 2 and Fig. 1).

| Symptom . | Average before RFTC (SDEV) . | Average after RFTC (SDEV) . | P-value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pain | 1.1 (0.31) | 0.3 (0.57) | <0.05 |

| Itching | 1.7 (0.80) | 0.3 (0.48) | <0.05 |

| Bleeding | 2.1 (0.36) | 0.3 (0.57) | <0.05 |

| Soiling | 0.6 (0.50) | 0 | <0.05 |

| Haemorrhoidal prolapse | 1.45 (0.50) | 0.1 (0.44) | <0.05 |

| Symptom . | Average before RFTC (SDEV) . | Average after RFTC (SDEV) . | P-value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pain | 1.1 (0.31) | 0.3 (0.57) | <0.05 |

| Itching | 1.7 (0.80) | 0.3 (0.48) | <0.05 |

| Bleeding | 2.1 (0.36) | 0.3 (0.57) | <0.05 |

| Soiling | 0.6 (0.50) | 0 | <0.05 |

| Haemorrhoidal prolapse | 1.45 (0.50) | 0.1 (0.44) | <0.05 |

| Symptom . | Average before RFTC (SDEV) . | Average after RFTC (SDEV) . | P-value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pain | 1.1 (0.31) | 0.3 (0.57) | <0.05 |

| Itching | 1.7 (0.80) | 0.3 (0.48) | <0.05 |

| Bleeding | 2.1 (0.36) | 0.3 (0.57) | <0.05 |

| Soiling | 0.6 (0.50) | 0 | <0.05 |

| Haemorrhoidal prolapse | 1.45 (0.50) | 0.1 (0.44) | <0.05 |

| Symptom . | Average before RFTC (SDEV) . | Average after RFTC (SDEV) . | P-value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pain | 1.1 (0.31) | 0.3 (0.57) | <0.05 |

| Itching | 1.7 (0.80) | 0.3 (0.48) | <0.05 |

| Bleeding | 2.1 (0.36) | 0.3 (0.57) | <0.05 |

| Soiling | 0.6 (0.50) | 0 | <0.05 |

| Haemorrhoidal prolapse | 1.45 (0.50) | 0.1 (0.44) | <0.05 |

Average values of HSS 3 weeks before and 2–3 months after procedure.

Pain

Post-operatively all patients were provided with routine oral analgesics, including paracetamol, codeine and ibuprofen to take when required. None of the patients required any stronger analgesia, such as tramadol or morphine sulphate. The results illustrate that the majority of patients post-operatively on Day 3 had a pain score between 1 and 3 with only patients scoring 7–9 requiring PO analgesia. Only one patient returned to the hospital with pain that could not controlled with conventional analgesia (Table 3).

| Visual analogue pain score . | 0 . | 1–3 . | 4–6 . | 7–9 . | 10 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 3 | 1 | 11 | 3 | 5 | 0 |

| Day 7 | 13 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Visual analogue pain score . | 0 . | 1–3 . | 4–6 . | 7–9 . | 10 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 3 | 1 | 11 | 3 | 5 | 0 |

| Day 7 | 13 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Visual analogue pain score . | 0 . | 1–3 . | 4–6 . | 7–9 . | 10 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 3 | 1 | 11 | 3 | 5 | 0 |

| Day 7 | 13 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Visual analogue pain score . | 0 . | 1–3 . | 4–6 . | 7–9 . | 10 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 3 | 1 | 11 | 3 | 5 | 0 |

| Day 7 | 13 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

The SAPS [10]

All 20 patients were interviewed via phone call interviews. Responses were recorded electronically and SAPS scores were calculated individually. All patients obtained a score between 19 and 16, which represents the ‘Satisfied’ result after their treatment. All the patients were asked about the areas of health care they found unsatisfactory. The results were audited and reported via an audit to enable improvements to the surgical management of this condition.

DISCUSSION

One of the most innovative methods of the treatment of HD in the twenty-first century is RFTC. With appropriate case selection and surgical treatment of a maximum of three haemorrhoids at one time it can achieve the return of haemorrhoidal tissue to normal anatomy without any big trauma of the mucosa and surrounding tissue.

In comparison to monopolar energy, RFTC remains a cold device with the probe being just a source of very high frequency waves, which are delivered at 4 MHz [11, 12]. The use of RFTC leads to a decrease in the blood flow to affected tissue followed by fibrosis and scarring, resulting in a tethering of the mucosa to the underlying tissue and preventing haemorrhoidal prolapse [4, 12].

This atraumatic technique minimises pain, blood loss and local oedema [11, 12]. Unlike finger switch diathermy, the RFTC probe does not need to cool down, which makes the procedure quicker and better tolerated by the patients [12, 13].

Antibiotic cover is not mandatory as the RFTC-coagulated area is aseptic and the probe is thought to provide an additional sterilisation role [12, 14].

This single-centre study reports the learning curve for RFTC in the treatment of HD in 20 successive cases. During the study, we standardised our operative method, and we defined the inclusion–exclusion criteria for the bigger trial ‘ORION’. Standardisation of operative technique reduces variability and makes it reproducible between surgeons from our Trust and elsewhere. All follow-up clinics were completed in a structured way, which enables a complete dataset for analysis. One of the main observations of the study is that the majority of the patients are free from pain 7 days post-procedure and there is a significant decrease of HSS score in each symptom 3 and 6 months post-operatively.

After the RFTC treatment, eight complications were reported to have occurred (Table 4). None of the patients required further operative management, but three of the patients were readmitted because of bleeding. The readmitted patients were found to suffer from cardiac comorbidities, which were treated with anticoagulants and antiplatelet drugs. The average time of work for our cohort is 7 days.

| Complications . | Value (%) . |

|---|---|

| Minor bleeding | 2 (10) |

| Bleeding that requires admission | 3 (15) |

| Pain | 2 (10) |

| Urinary retention | 0 |

| Infection | 0 |

| Anal stenosis | 0 |

| Recurrence | 1 (5) |

| Complications . | Value (%) . |

|---|---|

| Minor bleeding | 2 (10) |

| Bleeding that requires admission | 3 (15) |

| Pain | 2 (10) |

| Urinary retention | 0 |

| Infection | 0 |

| Anal stenosis | 0 |

| Recurrence | 1 (5) |

| Complications . | Value (%) . |

|---|---|

| Minor bleeding | 2 (10) |

| Bleeding that requires admission | 3 (15) |

| Pain | 2 (10) |

| Urinary retention | 0 |

| Infection | 0 |

| Anal stenosis | 0 |

| Recurrence | 1 (5) |

| Complications . | Value (%) . |

|---|---|

| Minor bleeding | 2 (10) |

| Bleeding that requires admission | 3 (15) |

| Pain | 2 (10) |

| Urinary retention | 0 |

| Infection | 0 |

| Anal stenosis | 0 |

| Recurrence | 1 (5) |

We were able to produce equivalent results to previous published literature like Eddama et al. [7], which has shown a similar reduction in symptoms post-procedure. Despite the fact that the assessment of satisfaction was done in two different methods, the final scores match to the patient cohort.

Patients were followed up at 3 and 6 months post-procedure, which gives us the opportunity to detect any type of complications including recurrence.

Only a recurrence was found during the 6-month follow-up. The reasons for recurrence are felt to be multifactorial including high-grade disease, and lifestyle factors, such as dietary intake and infrequent bowel motions.

The limitations of the study are first of all the fact that we included only the cases completed in our Trust, and that there is no second cohort to compare results with other methods of the treatment of HD.

This study supports that RFTC is a safe and acceptable method of treatment for HD. Although the satisfaction scores are promising, further randomised controlled trials are needed to confirm the true efficacy of this method. A further trial is currently started to create.

The study shows that radiofrequency coagulation could be adopted as a safe alternative to classic procedures in the treatment of HD, as it is a hassle free and safe procedure. Saving the initial cost of the instrument, it involves no expenses of a recurring nature. The application is easy and requires no special training. Being better tolerated by patients, it can be considered as an alternative procedure for early haemorrhoids.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

V.B. and A.M. collected and analysed data and wrote the manuscript. S.K. and V.S. contributed to manuscript preparation. R.B. was the senior author and contributed to data collection, analysis and manuscript preparation.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

FUNDING

None.

DATA AVAILABILITY

Anonymised data can be provided for data transparency.

References

Lee MJ, Morgan J, Watson JM, Jones GL, Brown SR.

Hawthorne G.