-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Travis Fahrenhorst-Jones, Jane E Theodore, Emilia L Dauway, Hidradenitis suppurativa of the breast: a diagnostic dilemma, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2023, Issue 2, February 2023, rjad045, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjad045

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a chronic skin condition characterised by recurrent abscesses, nodules, sinus tracts and fistulas. The condition has a known diagnostic delay and well-documented negative effect on the quality of life of patients. When affecting the periareolar region, there is a capacity for confusion with other more mainstream surgical conditions of the breast. We present a case of a 35-year-old woman who was diagnosed with an acutely painful breast nodule with periareolar erythema and induration who was repeatedly misdiagnosed due to cofounding features on clinical assessment. We present this case as a diagnostic dilemma to raise awareness of HS as a differential when assessing surgical breast patients.

INTRODUCTION

Diagnosis of periareolar hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) can be difficult due to overlap of clinical features with other more traditional surgical diagnoses of the breast. Typically inframammary in location, this case of periareolar HS we present demonstrates an uncommon presentation of skin-associated breast infection that was repeatedly misdiagnosed until careful reassessment by a specialist breast surgeon at our institution. We present this case as an exploration of diagnostic dilemma involved in a presentation confounded by risk factors and features shared with other diseases of the breast.

CASE REPORT

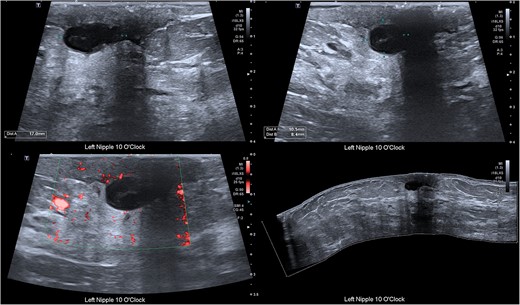

A 35-year-old non-lactating G1P1 woman was diagnosed with acute left breast pain on a background of a retroareolar lump. The patient experienced symptoms for less than 6 months. She had a past medical history of depression and anxiety, and was a current smoker. She was also allergic to penicillin. On examination there was left breast periareolar induration and erythema with an upper inner quadrant palpable solid, tender lesion adjacent to the nipple (Fig. 1). There was no right breast abnormality and no evidence of regional lymphadenopathy. An ultrasound suggested an infected epidermoid cyst and aspiration revealed mixed anaerobic bacteria (Fig. 2). The patient was prescribed antibiotics (clindamycin), discharged with advice to cease smoking and outpatient follow-up was arranged. The patient had two further admissions to hospital each within days of discharge for persistent symptoms.

Note cribriform atrophic scarring at 12 o’clock and 2 o’clock that was overlooked on initial examination.

Ultrasound of the breast demonstrating a cystic structure adjacent to the nipple measuring approximately 17 mm × 11 mm × 8 mm with surrounding inflammatory changes and low-level internal echoes. No internal flow.

At the second admission, a diagnosis of periductal mastitis (PDM) was made, given the persistence of symptoms and the significance of her smoking history. The management was with repeat ultrasound guided aspiration of abscess and antibiotics (metronidazole) guided as per prior cultures. At the third admission anchoring to PDM led to further aspirations, and the patient’s antibiotic cover was broadened (cephazolin, lincomycin and metronidazole) as per cultures and specialist infectious diseases advice. Symptoms persisted despite treatment. Patient dissatisfaction grew, impacting her social circumstances, leading to a second opinion being sought.

Upon review by a second breast surgeon, a more detailed history revealed recurrent axillary abscesses that the patient had been self-draining in the community for several years. The patient revealed a family history suggestive of HS. Initially overlooked scarring and sinus tract formation at the periareolar aspects of the breasts and axillae were also noted on examination (Fig. 3). A diagnosis of HS was considered.

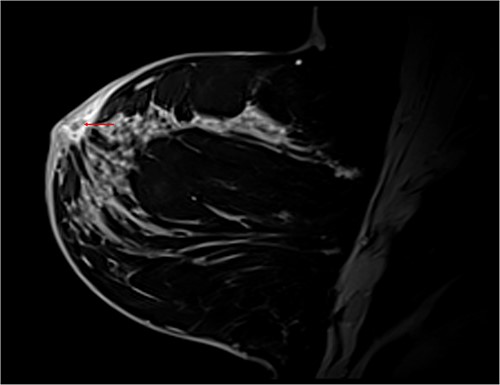

Differential diagnoses included granulomatous mastitis (GM) and inflammatory breast cancer (iPrevent score of 11.2% lifetime risk) [1]. A complete triple assessment was performed with bilateral breast imaging and core biopsy of the retroareolar lesion. Magnetic resonance imaging demonstrated benign breast changes and histopathology demonstrated suppurative chronic inflammation with granulation tissue and adjacent fibrosis without evidence of granulomas or malignancy (Fig. 4). Doxycycline was commenced with significant clinical improvement, supporting an HS diagnosis. The patient was discharged with ongoing multidisciplinary management involving a breast surgeon, an infectious diseases physician and a dermatologist.

T1 Dixon sagittal MRI of the breast—changes restricted to the skin. Diffuse skin thickening of the periareolar region with small fluid collections (red arrow).

DISCUSSION

Previously thought to be an infectious disorder of apocrine sweat glands, recent research has suggested that HS may be related to dysregulation of skin immunity adjacent to hair follicles in the intertriginous regions [2]. Skin lesions are heterogenous involving recurrent painful nodules or abscesses, scarring and fistulas. The most common sites affected include the groin, axilla and inframammary folds with women being more commonly affected than men with a male to female ratio of 1:2.7 to 1:3.3 [3]. Although the exact mode of inheritance is unclear, HS does have a hereditary component to its presentation that may be elicited on history [4].

Diagnosis of HS relies on three criteria: characteristic lesions, disease in predilection areas and chronicity with recurrence [3]. Given that inframammary locale is more typical, periareolar HS was not immediately considered as a differential by the surgical team [2]. The subtle periareolar features and chronicity with recurrence of the axillary lesions were not recognised. A diagnosis of HS can significantly impair quality of life as demonstrated in this case with a significant diagnostic delay noted in the literature [5–7]. Had these features been recognised on previous presentations, the patient may have been diagnosed at an earlier stage.

Delay in diagnosis stemmed from a lack of recognition of periareolar HS on clinical assessment as well as cofounding features shared with other breast conditions. Like PDM, HS has a strong association with tobacco smoking with some authors reporting a prevalence of as high as 90% among HS sufferers [4]. Further, a chronic painful retroareolar breast mass in a parous previously lactating woman is typical of GM [8, 9]. Given serious implications if overlooked, the possibility of malignancy was also considered given the persistence of symptoms despite treatment. There exists at least one case report of HS masking cutaneous breast carcinoma [10]. Ultimately, HS is a clinical diagnosis without a confirmatory test [11]. Although differentials were ruled out via imaging and histopathology in our case, the diagnosis was secured on clinical grounds through targeted history taking, careful examination and trial of medical treatment.

Treatment of HS is predominantly medical, with tetracyclines being central and there is a role for biologics in severe cases [12]. Although the incision and drainage of abscesses may relieve acute symptoms, scarring often results in a poor cosmetic outcome and does not prevent relapse. Excision of affected skin is only effective in approximately half of patients [4].

In summary, the delay in accurate diagnosis articulates the need for surgeons to have an appreciation for stigmata of HS on history and examination in cases of periareolar inflammation. The described case and clinical images serve to provoke vigilance for HS among surgeons and prevent diagnostic misadventure.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We acknowledge and thank the patient for providing consent for this case report, allowing us to share her story.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

FUNDING

None.