-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Joseph Phillipos, Afaq Khan, Neil Jayasuriya, Differentiation of benign nevoid rests and metastatic melanoma in sentinel lymph node biopsy, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2023, Issue 2, February 2023, rjad036, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjad036

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Patients with cutaneous melanoma routinely undergo sentinel lymph node (SLN) biopsy. If this first lymph node is clear, the entire lymph node basin is very likely to be free from the metastatic disease. Lymph node analysis is therefore of great importance with respect to prognostication and further management. Various cell types, including benign nevoid rests, can mimic metastatic melanomatous cells in the SLN. There is no standardized method to differentiate naevoid rests from metastatic melanoma. Diagnosis is based on cell location, morphology and multiple immunohistochemical techniques, with no single test being completely diagnostic. We present a patient with Lentigo Maligna melanoma, who was found to have benign nevoid rests on SLN biopsy, and discuss the diagnostic tests and considerations in differentiating benign nevoid rests from metastatic melanoma.

INTRODUCTION

The sentinel lymph node (SLN) biopsy, first described by Morton [1], is based on the hypothesis that tumour cells metastasize to the first nodes receiving lymphatic drainage before involving other lymph node tiers. If this first node, known as the SLN, is clear, the entire lymph node basin is highly likely to be free from tumour cells [1, 2]. In patients with cutaneous melanoma with risk of regional nodal metastasis, SLN biopsy is routinely performed. Identification of malignant cells in lymph nodes can prove to be challenging because multiple cell types, including benign nevoid rests, can mimic malignant melanomatous cells. There is no definitive test to diagnose metastatic melanoma, and there is an overlap in cytomorphology and immunohistochemical (IHC) staining patterns between metastatic melanoma and nevoid cells. Differentiation has to made in SLN biopsy, as it has implications for prognostication and management. Diagnosis entails a multi-faceted approach and may include a second histopathologist’s opinion.

CASE REPORT

We present a 53-year-old male truck driver, who presented with an ill-defined, palpable brown nodular lesion on the posterior aspect of his left forearm, measuring ~12 × 10 mm. He was a non-smoker and denied spending significant amounts of time in the sun. Duration of the presence of the lesion was unknown.

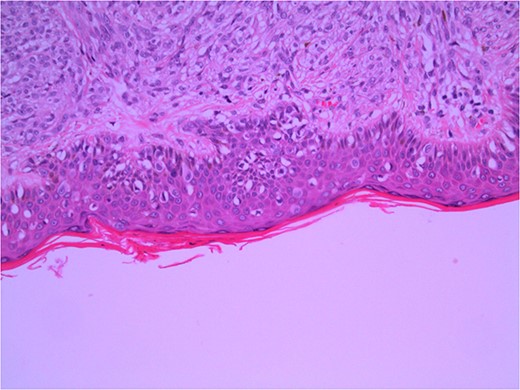

Excisional biopsy of the primary lesion was performed by his general practitioner which confirmed the diagnosis of Lentigo Maligna melanoma. Breslow thickness was 1.9 mm, and the deep margin demonstrated an invasive component to 2 mm, equating to Clark 4 invasion. Junctional melanocytes showed moderate to marked atypia, with sheets of melanocytes in the dermis (Fig. 1). There was no ulceration or lymphovascular invasion. This was followed by wide local re-excision. Adjacent epidermis showed a mild increase in atypical melanocytes, with no contiguous proliferation. No residual in situ or invasive malignancy was detected. He underwent a staging computed tomography (CT) that did not identify distant metastases.

Wide local excision of primary lesion demonstrating pagetoid spread in epidermis and infiltration into reticular dermis; H&E × 200 magnification.

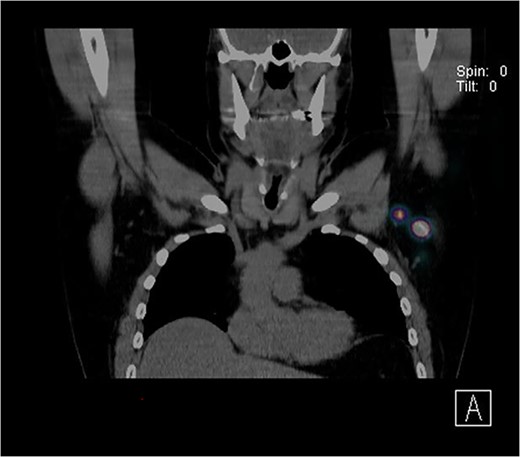

Further wide local excision was performed with margins of 2 cm to deep fascia and keystone flap reconstruction. SLN biopsy was carried out, with dual localization of SLN with Patent Blue V and radio nucleoid tracer. The preop CT single-photon-emission computed tomography (SPECT) imaging showed a focus of tracer activity in two SLNs in the left axilla (Fig. 2). The two lymph nodes were harvested with standard technique.

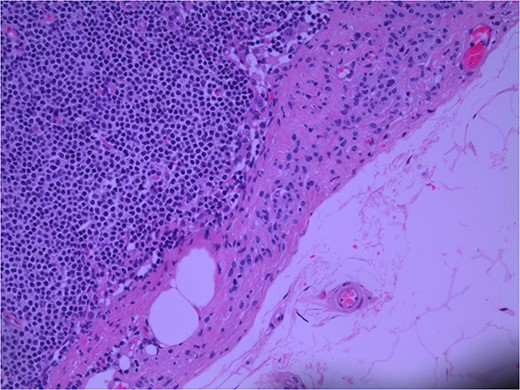

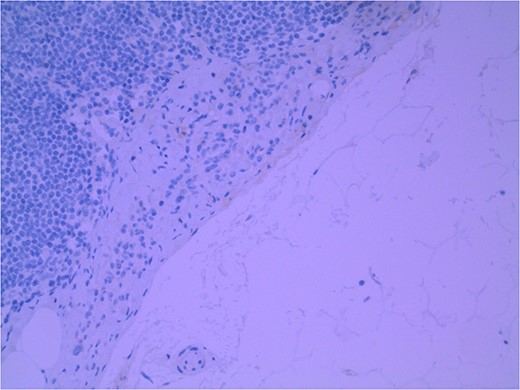

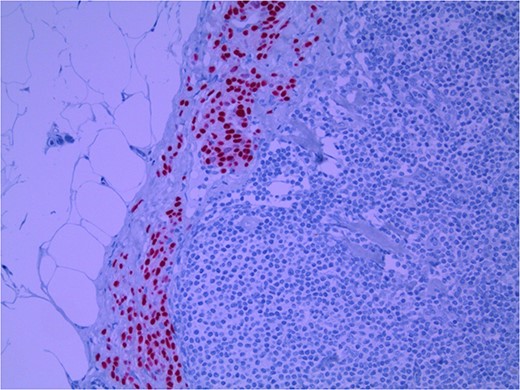

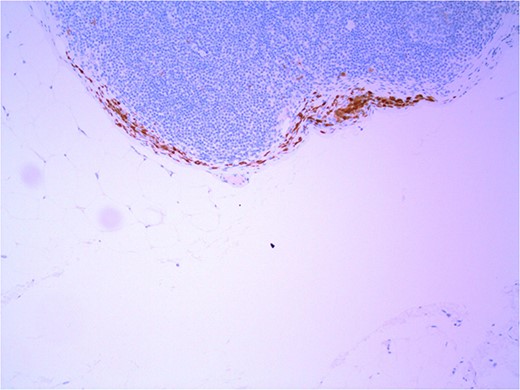

Lymph node specimens were sent for haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining (Fig. 3) and IHC analysis. The sections showed mild reactive changes and benign intracapsular nevoid rests. IHC analysis showed that these cells were negative for HMB-45 (Fig. 4) and were positive for both Sox10 and p16 (Figs 5 and 6). Consensus at the Multidisciplinary Team Meeting was that the appearance was in keeping with benign naevoid rests as opposed to melanoma deposits, given the location of the cells, morphology and immunohistochemistry. Surveillance was recommended.

Lymph node; nevoid melanocytes in subcapsular region; H&E × 200 magnification.

Lymph node with IHC using HMB-45 stain, not staining subcapsular region melanocytic cells; × 200 magnification.

Lymph node with IHC using Sox 10 stain, staining melanocytic cells (benign or malignant) in subcapsular region; × 200 magnification.

Lymph node with IHC using p16 stain, staining nevoid melanocytes; × 100 magnification.

DISCUSSION

Naevoid rests are benign embryological remnants of melanocytic cells. Patients with benign naevus cell aggregates in SLN biopsy have a prognosis similar to patients with negative lymph nodes and do not require further intervention [3]. Patients with lymph nodes positive for metastatic melanoma may require adjuvant systemic therapy and/or surgical resection [4, 5]. Similarities in cytomorphology and architecture as well as IHC markers can make differentiation difficult [3, 6].

Currently, the gold standard for diagnosis of melanoma involves tissue morphology and histopathology of the primary lesion. Histopathological diagnosis incorporates architectural, cytologic and host response features, with atypical melanocytes and architectural disorder required. The Australian Clinical Practice Guidelines state that SLN biopsy should be considered in patients with cutaneous melanoma >1 mm in thickness or >0.8 mm with high risk pathological features [7]. SLN biopsy is a multi-step procedure. The first step is lymphoscintigraphy in which a radioactive tracer is injected. Gamma camera imaging is used preoperatively and a gamma probe aids in the correct identification of the SLN/s intraoperatively. Localized SLN/s are then removed and are assessed for the presence of metastatic disease. Intranodal melanocytes usually indicate metastatic disease [8], however, benign naevoid rests can occasionally present in lymph nodes.

Lymphatic drainage enters the node at the level of the subcapsular sinus; thus, most nodal metastasis are found in the subcapsular region [9]. Naevoid rests are usually found within the nodal fibrous capsule and nodal trabeculae, as was the case for the current patient. Naevoid rests can present in the subcapsular region, complicating the interpretation of lymph node status.

H&E staining is the gold standard for lymph node evaluation, and IHC staining is used to improve sensitivity and specificity [10–13]. Similar to the staining of the primary lesion, there is an overlap between the commonly used markers, and no single marker has 100% specificity or sensitivity.

Several IHC stains are in use in the pathological interpretation of primary lesions and SLN biopsies. The antibody HMB-45 reacts with most melanomas. In a primary lesion, HMB-45 is immunoreactive with intraepidermal and superficial dermal components of benign nevi [14]. In a lymph node, however, benign nevoid cells are negative for HMB-45 and appear bland. A loss of HMB-45 expression has been reported in 20% of melanocytic metastasis, illustrating the need for further diagnostic testing [14]. Sox10 is a nuclear transcription factor that stains benign and malignant melanocytic cells. It indicates the extent of melanocytic spread but does not differentiate between benign nevi and metastatic melanoma [15]. Immunostaining for the tumour suppressor gene p16 differentiates between benign naevi and melanocytic metastases in the SLN. One study demonstrated positive nuclear and cytoplasmic p16 staining in all nevi (dermal and lymph node) and the absence of nuclear p16 staining in all but one melanoma metastasis [14]. No single stain is completely sensitive for melanocytic metastases, and a confident diagnosis relies upon cell location, morphology and multiple IHC techniques. SLN biopsy in the current patient demonstrated intracapsular melanocytic cells which stained negative for HMB-45, and positive for Sox10 and p16, in keeping with benign nevoid rests as opposed to metastatic melanoma.

Differentiation between melanoma and benign nevus is highly important for patient outcomes and resource allocation, however, similarities in cytomorphology and IHC techniques for both diagnosis of the primary lesion and interpretation of SLNs can make diagnosis and staging problematic. Differentiating between benign naevoid rests and metastatic melanomatous cells requires multiple pathological techniques and consideration of cell morphology and location.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

FUNDING

None.