-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Anupama Barua, Lucy Cosbey, Ravish Jeeji, Lognathen Balacumaraswami, Early life threatening constrictive pericarditis following off-pump CABG, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2023, Issue 10, October 2023, rjad602, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjad602

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

We present a unique case of aggressive symptomatic constrictive pericarditis within one month following off pump coronary artery bypass grafting surgery. The patient had a medical history of Hodgkin’s lymphoma treated with radiotherapy and chemotherapy 20 years ago. Investigations confirmed constrictive pericardium with patent grafts and good biventricular function. Pericardiectomy was successful with remarkable recovery of symptoms.

Introduction

Constrictive pericarditis following radiotherapy (RT) is not uncommon and occurs in 9% of patients [1]. Though an acute inflammatory change in the pericardium starts at the time of exposure to radiation, constrictive pericarditis becomes evident decades after receiving radiotherapy. RT also causes coronary artery disease, valvular heart disease, and arrhythmia [2]. In particular, coronary artery disease occurs earlier than general population due accelerated atherosclerosis following radiotherapy [2, 3].

We present a patient with mobility restricted to 10 yards and gross ascites due to aggressive constrictive pericarditis. This occurred 1 month after off pump coronary artery bypass grafting. He received radiotherapy to treat Hodgkin’s lymphoma two decades ago. He made a gradual but remarkable recovery after pericardiectomy and walks 5 miles a day.

Case report

A 52-year-old male presented with progressive shortness of breath one month following off pump coronary artery bypass grafting due to severe peripheral oedema with ascites and he was totally bed bound due to gross fluid retention. He had right internal thoracic artery to left anterior descending artery, great saphenous vein to obtuse marginal artery and great saphenous vein to right coronary artery. His left internal thoracic artery was calcified from radiotherapy. He had radiotherapy for Hodgkin’s lymphoma 20 years previously and remained completely disease free for two decades. Repeat coronary angiogram revealed patent coronary grafts. Transthoracic echocardiogram showed ejection fraction 50%, a dilated right atrium and inferior vena cava. Cardiac MRI revealed both ventricles with normal systolic function although chamber volumes and low indexed stroke volumes, no evidence of reversible ischaemia on stress perfusion. There was evidence of active pericardial inflammation, thickening and pericardial effusion with constrictive physiology, including enhanced ventricular interdependence, septal bounce and loss of myocardial slippage with dilatation of the IVC and hepatic veins. Overall findings were consistent with an effusive-constrictive picture in acute inflammation stage.

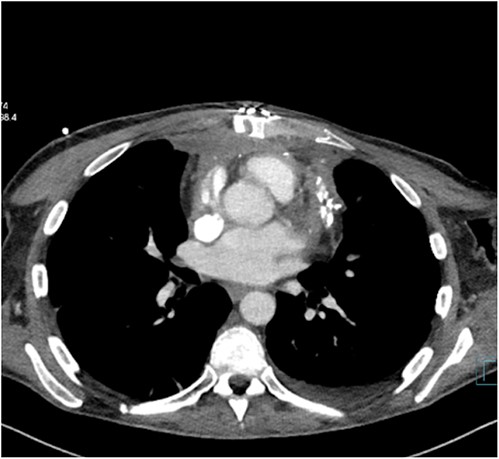

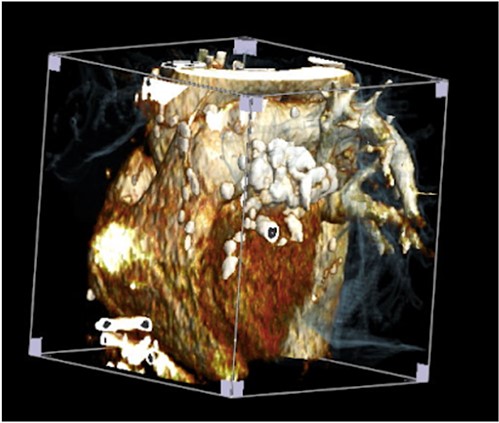

The patient was treated with anti-inflammatory drugs (colchicine), steroids and diuretics. Repeat MRI in 4 months’ time showed significant organized material within the pericardial space with associated pericardial thickening. There was both septal ‘bounce’/ ‘shudder’ and significant respirophasic septal shift on free-breathing, consistent with enhanced ventricular interdependence suggestive of constrictive physiology. CT scan revealed calcified and thickened pericardium (Figs 1 and 2).

His blood result revealed deranged liver function with high CRP. Several litres of peritoneal fluid were drained on multiple occasions. Symptoms were unabated. The patient was taken to theatre for pericardiectomy.The thick fibrotic pericardium, measuring 2 cm, encasing the heart especially around superior and inferior venacava was identified. Extensive pericardiectomy was performed without cardiopulmonary bypass. Histopathology revealed pieces of pericardial fibroadipose tissue with significant hyaline fibrosis and patchy chronic inflammation including multinucleated giant cells and lipogranulomas. There were foci of degenerate collagen surrounded by histiocytes without any Hodgkin or Reed–Sternberg cells. Ziehl–Neelsen staining revealed no mycobacterial organisms. Markers (CD20, CD7a, and PAX5) highlighted heterogenous B-lymphocytes with no atypical cells. CD15, CD30, and MUM-1 were negative for Hodgkin cells. The features were consistent with non-specific chronic inflammation, fat necrosis, and pericardial fibrosis. There was no evidence of malignancy.

The patient made gradual recovery and was discharged home in 3 week. Follow-up echocardiogram revealed good biventricular function and ejection fraction 56%.

Discussion

Radiotherapy causes endothelial damage and neovascularization results in fibrotic changes to the pericardium and coronary atherosclerosis. Here, we present a case of latent activation of occult inflammatory pericarditis. This is an interesting case of a patient following uneventful off pump coronary artery bypass grafting who developed aggressive constrictive pericarditis within a month after surgery. At the time of bypass operation, we found old calcific pericardium adherent to left side of the heart and a fibrotic left internal thoracic artery which are signs of RT damage. His symptoms developed initially as post cardiotomy symptoms or Dressler’s syndrome which was unresponsive to colchicine and steroid therapy. Additionally he required spironolactone and furosemide to treat ascites and gross fluid overload.

Pericardectomy is the definitive treatment for symptomatic patients following cardiac surgery [4]. Prior coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) poses a higher risk with patent RItA graft travelling across beneath the sternum susceptible for injury during redo sternotomy. Other grafts are susceptible to injury at the time of dissection of the pericardium as SVG was grafted to OM1 and SVG was traveling in front of the right ventricle. CT scan and MRI are useful for diagnosis of the disease. We performed echocardiogram, CT scan and MRI for the confirmation of the diagnosis [5].

Several authors suggested partial or anterior pericardiectomy to mitigate the risk of potential injury to the patent grafts [6]. Left anterolateral thoracotomy was suggested to avoid the damage to the conduit behind the sternum [7]. However, this approach will not allow the release of the right side the heart and the constrictive rings surrounding the superior vena cava and inferior vena cava cannot be addressed which may lead to non-resolution of symptoms of pericarditis [8].

Radiotherapy improves the survival of the patients in Hodgkin’s lymphoma [1–3]. The risks of developing cardiovascular disease are higher after radiotherapy. The time interval between the developments of chest symptoms is very prolonged. Early diagnosis predicts better prognosis in cardiovascular disease. The rigorous follow-up is warranted after radiotherapy for positive impact of patient care.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Funding

None declared.

Data availability

All data (of the patient) generated during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Author contributions

AB prepared the manuscript. LC organized the figures. RJ and LB reviewed the manuscript and suggested changes.