-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Teagan Fink, Wei Wei Yong, Neil Jayasuriya, Stricturing ileocaecal endometriosis: a rare concurrent aetiology in a patient with Crohn’s disease, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2023, Issue 1, January 2023, rjac605, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjac605

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

A 34-year-old female presented with colicky abdominal pain and symptoms suggestive of subacute small bowel obstruction in the setting of Crohn’s disease (CD). She was on maximal medical therapy and had undergone endoscopic balloon dilatation of a terminal ileal stricture on two occasions. Magnetic resonance enterography demonstrated acute inflammation in two segments of the terminal ileum. The patient proceeded to laparoscopic ileocolic resection. The histopathology revealed a segment of stricturing CD with chronic inflammatory change. There was also an unexpected finding of a segment of stricturing ileal disease secondary to endometriosis. Endometriosis affecting the ileum is uncommon, and concurrent CR and endometriosis is very rare. Further research is required to understand whether these two conditions are associated. Here, we present a discussion on the histopathology differences between endometriosis and CD. Clinicians are reminded of these rare concurrent conditions, as the symptomatology may mimic one another, thus impacting the treatment and management.

INTRODUCTION

We present a rare case of concurrent stricturing Crohn’s disease (CD) and endometriosis of the terminal ileum causing subacute small bowel obstruction. An overview of the literature and differences in histopathological findings are discussed as well as salient information for surgeons who may encounter these rare concurrent diseases.

CASE REPORT

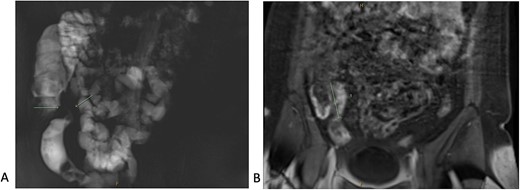

A 34-year-old female presented with colicky episodic abdominal pain and symptoms suggestive of subacute small bowel obstruction in the setting of known stricturing CD. Her symptoms were poorly controlled on multiple medications—Azathioprine, Mesalazine, Adalimumab and Budesonide. She had no previous history of abdominal surgery or gynaecological pathology. She had twice undergone endoscopic balloon dilatation of a terminal ileal stricture with short-lived symptomatic relief. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis showed a short segment of acute inflammation of the terminal ileum (Fig. 1) and an incidental right adnexal cyst. Pelvic ultrasonography was normal. Magnetic resonance enterography confirmed stricturing CD with two segments of inflammation of the terminal ileum (lengths of 5 and 3.8 cm) approximately 5 cm from the ileocaecal valve (Fig. 2).

Computed tomography scan (portal venous phase post intravenous contrast) showing a short segment of thickened, enhancing terminal ileum consistent with terminal ileitis of CD.

Magnetic resonance enterography demonstrating strictures of the small bowel (A) in a segment of terminal ileitis with acute inflammation (B).

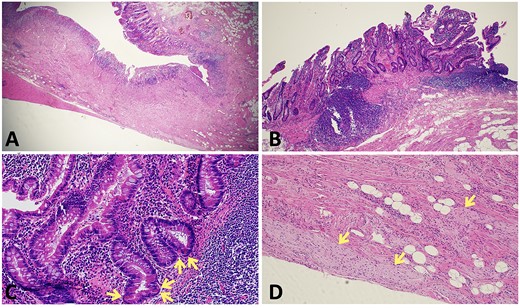

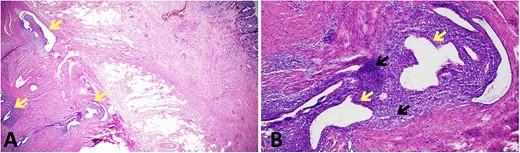

The patient proceeded to an elective laparoscopic ileocolic resection with a side-to-side stapled anastomosis. Macroscopically, there was a stricture of the proximal ileum with associated small bowel wall dilatation and ulceration and cobble stoning of the terminal ileum. Histopathology confirmed stricturing CD—with acute on chronic inflammation, fissuring ulcer formation, reactive epithelial hyperplasia, chronic inflammatory change and smooth muscle hypertrophy (Fig. 3). A second distinct stricture confirmed an endometriotic deposit in the muscularis externa and submucosa with associated haemosiderin-laden macrophages (Fig. 4). This was an unexpected finding of endometriosis in the terminal ileum, as there were no apparent endometrial deposits elsewhere at the time of laparoscopy.

Histopathological findings in CD; (A) H&E section (×20 magnification) showing fissuring ulceration, focal cryptitis, crypt abscess and background smooth muscle hypertrophy; (B) H&E section (×40 magnification) showing submucosal lymphoid aggregates and plasma cells; (C) H&E section (×200 magnification) showing Paneth cell metaplasia (arrows); (D) H&E section (×100 magnification) showing Nerve twig hypertrophy (arrows) at the base of the ulcer.

Histopathological findings in endometriosis; (A) H&E section (×20 magnification) showing endometriotic foci (arrows) within the muscularis propria, terminal ileal mucosa is seen in the top right corner; (B) H&E section (×100 magnification) showing a magnified view of an endometriotic focus which comprises of ectopic endometrial glands (yellow arrows) surrounded by ectopic endometrial stroma (black arrows); focal haemosiderin-laden macrophages are also present in the background of ectopic endometrial stroma.

DISCUSSION

CD is a heterogeneous disease of no known aetiology affecting males and females (with peak incidence in the second decade of life) [1]. CD results in transmural inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract, leading to episodic colicky abdominal pain, altered bowel habits and per-rectal bleeding. CD management includes nutritional and psychosocial support with medical therapies, and up to two-thirds of patients require surgery [1]. Endometriosis is a benign oestrogen-dependent condition affecting 5–15% of menstruating women (peak incidence is at 30–45 years of age) [2]. The exact pathophysiology of endometriosis remains unclear [3]. Retrograde menses leads to endometrial cell deposits in the abdomen and pelvis, which then grow in response to cyclical oestrogen exposure. In severe cases, deeper nodules with fibrosis and adhesions cause strictures and infertility [2, 3]. Rarely endometriosis affects the gastrointestinal tract—just 1–7% of cases have terminal ileal endometriosis [4, 5]. There is a positive association between inflammatory bowel disease (including CD) and endometriosis [2, 6], and patients with concurrent CD and endometriosis are more likely to have stricturing disease [7]. Cases of concurrent endometriosis and CD of the terminal ileum are rare [2].

Workup of CD and endometriosis

Radiologically, CD is characterized by skip lesions showing mucosal enhancement and luminal wall thickening and by fistulae in severe cases [1]. Endometriosis can be difficult to diagnose radiologically. Magnetic resonance imaging has the highest sensitivity rate to detect endometrioma deposits, mucosa enhancement or stricturing disease [4]. Both endometriosis and CD may cause strictures of the small intestine, and radiologically, these conditions can mimic one another [4]. Endoscopically, the hallmarks of CD include longitudinal skip lesions with aphthous ulceration, deep pit ulceration, cobble-stoning of the mucosa and rectal sparing [1, 8, 9]. Endometriosis of the gastrointestinal tract spares the mucosa (it affects the submucosa and muscular propria); thus, it may not be suspected at endoscopy, and biopsies may be inconclusive [4, 5]. Surgical pathognomonic findings of CD include a thickened, stiff mesentery that wraps around the small bowel colon [10]. Non-specific adhesions, stricturing and scarring may be seen in CD and endometriosis. Laparoscopy is considered to be diagnostic and therapeutic for endometriosis, with key findings of endometrioma deposits on reproductive organs, in the rectovaginal space or abdominal viscera [11]. Patients with endometriosis of the terminal ileum may be misdiagnosed and managed as CD until surgical resection and histopathological confirmation of endometriosis [2, 4, 5].

Histopathological features, molecular findings and associations

Diagnosis of CD and endometriosis relies on distinct histopathological findings [9, 11]. In CD, the typical morphological features include acute on chronic inflammation in some or all bowel wall layers. Active inflammatory changes include neutrophilic cryptitis, crypt abscesses, aphthous lesions and increased lymphocytes. The features of chronicity are fissuring ulcers and sinus tracts, which begin at the base of aphthous lesions and extend deeper in the bowel well layers. Other features of chronic inflammation include crypt architectural distortion, pseudopyloric Paneth cell metaplasia, submucosal fibrosis, neuronal and muscular hypertrophy and non-caseating granulomas.

In endometriosis, ectopic endometriotic epithelium (ER and PR are positive) and stroma (CD10 positive) are present, where the epithelial component is composed of endometrial glands lined by inactive cuboidal-columnar epithelial cells, or proliferative/secretory-type endometrium. Menstrual haemorrhage is common, and evidence of chronic haemorrhage (haemosiderin deposition and haemosiderin-laden macrophages) may provide a clue to the diagnosis of endometriosis—which is confirmed with at least two of these three findings.

CD has a higher incidence among relatives, disease concordance between twins and increased incidence in some populations. Significant advances in the understanding of the biology and genetic associations of CD have occurred in the past decade [6, 12–14]. At least, 71 CD genetic susceptibility loci have been identified [12].

First-degree family members have a three to nine times higher risk of developing endometriosis [11]. Endometriosis, ovarian clear cell carcinoma and endometrioid carcinoma share similar molecular alterations. Endometriosis in patients without malignancy also harbours oncogenic mutations in ARID1A, PIK3CA, KRAS and PPP2R1A, suggesting a neoplastic association [14].

Manifestations of CD (e.g. perianal abscesses or fistulas and inflammatory pseudotumours) have been described in intestinal endometriosis [15, 16]. These diagnostic dilemmas complicate morphological assessment, particularly in cases where mucosal biopsies are initially obtained for investigating gastrointestinal symptoms and where the typical features of endometriosis are absent or difficult to identify [17].

CONCLUSION

Concurrent endometriosis and CD affecting the ileum may rarely occur, and misdiagnosis may negatively impact patient care. Further research is required to understand the association between endometriosis and CD.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

FUNDING

There are no financial disclosures, sources of funding to disclose.

DATA AVAILABILITY

The data underlying this article can be shared on a reasonable request to the corresponding author, patient permission and ethics approval.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors received written consent from the patient to publish this case report. This study received ethics approval from the institution’s ethics review committee.