-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Germanico Fuentes, Gabriel A Molina, Marie A Jiménez, Sindy M Espinoza, A Gabriela Lara, Juan J Enriquéz, Andres V Ayala, Galo Jiménez, Cristina B Rubio, Intestinal ischemia in a patient with vascular malformation: a recipe for disaster, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2022, Issue 8, August 2022, rjac376, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjac376

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Anatomical variations of the celiac and mesenteric artery have been described over the past two centuries; many of these variations will have no clinical repercussions and will only be found incidentally or during imaging studies. However, these variations can lead to severe complications if undetected during surgery, transplantation or when they are affected by ischemia. Therefore, prompt treatment is needed to overcome these dangerous scenarios. We present the case of a 71-year-old patient who had a celiacomesenteric trunk and developed transient intestinal ischemia; however, he suffered severe acidosis and hyperlactatemia that ultimately led to organ failure and death.

INTRODUCTION

Most of the blood supply to the gastrointestinal tract comes from the celiac trunk and superior mesenteric artery [1, 2]. Rare anomalies of these vessels, such as the celiac-mesenteric trunk, can have serious clinical repercussions if compromised [2]. Injury to this trunk can have lethal effects on the body. Therefore, prompt diagnosis and treatment are vital, as time can be relentless in these scenarios [1, 2].

We present the case of a 71-year-old male patient who had a previously unrecognized celiacomesenteric trunk. He suffered transient intestinal ischemia, which, despite treatment, had a fatal outcome.

CASE REPORT

The patient is an otherwise healthy 71-year-old male. He had a 3-day history of mild abdominal pain, nausea and profuse diarrhea. Then, 24 h before admission, the pain and diarrhea worsened; suddenly, he became unresponsive; therefore, his family brought him in immediately.

On clinical examination, a hypotensive, tachycardic patient was encountered; he had severe pain in his lower abdomen with tenderness. However, no fever, masses or lymph nodes were discovered at that time. Complementary exams revealed a metabolic acidosis (pH < 7.2) and a serum lactate level over 6 mmol/L. Therefore, immediate intravenous fluid reanimation was required, and after the patient was stable, an abdominal computed tomography (CT) was requested.

On the CT, the whole extent of the bowel was dilated; however, no free liquid, air or masses were found (Fig. 1). Nevertheless, the patient’s abdominal pain and distention worsened. Due to this, surgical consultation was needed, and after obtaining consent, surgery was decided as intestinal ischemia was among the differential diagnosis.

On laparotomy, the full extent of the small bowel had a purplish color and was edematous, yet no perforation or necrosis was found. In some areas, the mesentery was engorged and had areas of ecchymosis; yet, the bowel had visible peristalsis and responded to reanimation maneuvers (Fig. 2).

Small bowel with a purplish color with areas of edema in the mesentery and hematomas.

To maintain a continuous assessment of the bowel vitality, a second-look surgical laparotomy was planned, and surgery was completed using a Bogota bag. Low-molecular-weight heparin was initiated, and the patient was transferred to the intensive care unit.

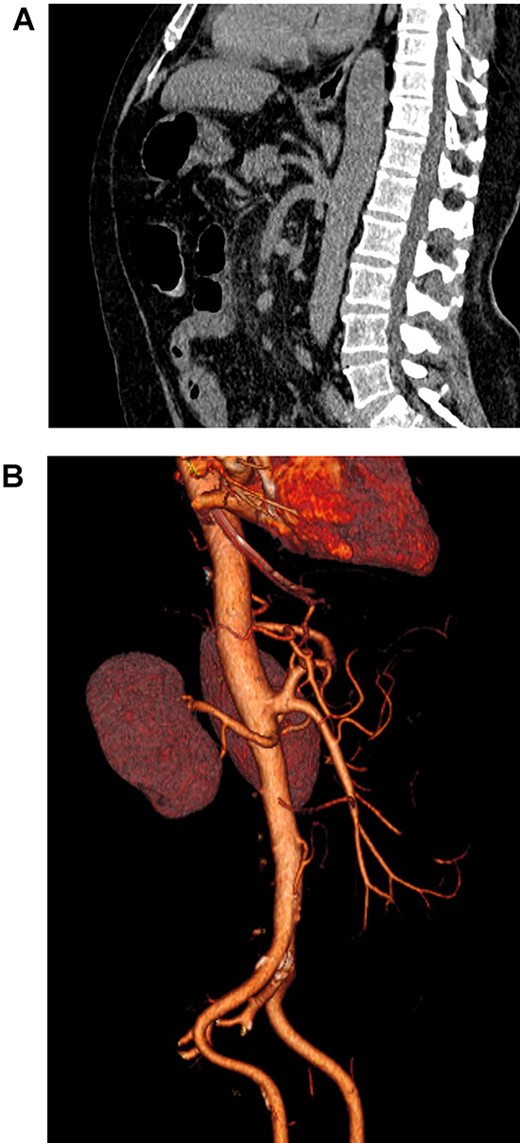

An angio-3D reconstruction of a patient’s CT scan was performed to rule out any vascular disease; although no thrombus or embolus was discovered, a vascular malformation of the superior mesenteric artery was found. The superior mesenteric artery and the celiac trunk arise from a common trunk, the celiacomesenteric trunk (Fig. 3A and B).

(A). Abdominal CT, showing the celiacomesenteric trunk. (B). Abdominal 3D reconstruction, revealing the vascular variation.

Twenty-four hours later, on the second laparotomy, the bowel loops were in better condition and regained their normal color and mobility (Fig. 4). However, the patient’s condition was complex; despite treatment and anticoagulation, he never fully recovered from his acidosis. The case worsened when he developed ventilator-associated pneumonia, which led to sepsis and refractory shock resulting in organ failure and, ultimately, death.

DISCUSSION

The celiac trunk and superior mesenteric artery are the primary vessels of the gastrointestinal tract [1, 2]. In the majority of people, the celiac trunk arises from the anterior portion of the aorta at the level of the 12 thoracic vertebra; from there, it splits into the left gastric, splenic and common hepatic artery; on the other hand, the superior mesenteric artery also arises from the anterior part of the aorta but lower at the level of the first lumbar vertebra [1–3].

Since the first description by Tandler et al. in 1908, it is believed that variations from the normal anatomy appear due to the lack of obliteration or persistence of the ventral longitudinal anastomoses in the primitive arterial plexus during fetal life [2, 3]. When the first to fourth roots are not obliterated, a common trunk is born from which the celiac trunk and the superior mesenteric artery arise [1, 4].

Many variations have been described since these vessels will change as the liver, pancreas, stomach and duodenum grow and have been extensively categorized in the Morita et al. and Michels et al. classifications [2, 5].

Celiacomesenteric trunk appears more frequently in Japanese and Korean populations and has no relation to gender [6]. This trunk is one of the rarest variations of the anatomy and has been reported in <0.5–1% of all individuals; it is usually a fortuitous discovery discovered during an autopsy, angiography or abdominal CT [1, 3]. Celiacomesenteric trunk has also been found in aneurysms, chronic occlusive disease, aortic dissection and celiac compression syndrome [2]. This variation must be assessed in liver transplantation, pancreatic, gallbladder and gastric surgery [2, 3].

Thrombosis of this trunk can be fatal, as Lovisetto et al. reported [7]. The stoppage of the only arterial trunk without collateral flow led to severe ischemia and death [5, 7].

We believe this could have happened to our patient. Because of his acidosis, the possibility of thrombosis in the celiacomesenteric trunk that was not seen in time was always possible. Otherwise, how to explain his severe acidosis and transient ischemia, which he could never fully recover from despite treatment?

More research is needed on the behavior of these variants in pathologies as severe as intestinal ischemia; having only one trunk and no collateral vascular network can be fatal.

CONCLUSIONS

A late diagnosis of intestinal ischemia is often lethal. If an additional anatomic variation can further compromise the bowel, such as the involvement of the celiacomesenteric trunk, the outcome will be even worse. In these diseases, time is of the essence. We cannot delay the diagnosis of these pathologies. It is essential to recognize them early to prevent these catastrophic complications and provide prompt treatment that could be life-saving if given in time.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

We have no conflict of interest to disclose.

FUNDING

None.