-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Andreas R de Biasi, Amish Raval, Gregory Tester, Satoru Osaki, Direct innominate artery access for transcatheter aortic valve replacement, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2022, Issue 7, July 2022, rjac330, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjac330

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Hostile vascular disease can pose a challenge for transcatheter aortic valve replacement, for which the preferred access is via a common femoral artery. However, extensive peripheral arterial disease may also preclude traditional points of alternative access in some patients. Herein, we describe two patients in whom successful transcatheter aortic valve replacement was performed via direct innominate artery access.

INTRODUCTION

Percutaneous common femoral artery access is well established as the preferred route for transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR). Patients with extensive peripheral arterial disease present a unique challenge for minimally invasive access, as alternative arterial sites like the axillary or common carotid arteries, may also be diseased. However, more morbid access locations, like transapical or traditional sternotomy approaches, are not necessarily requisite in all such cases—we are therefore presenting two octogenarian patients in whom TAVR was successfully performed via minimally invasive direct access of the innominate artery.

Case 1

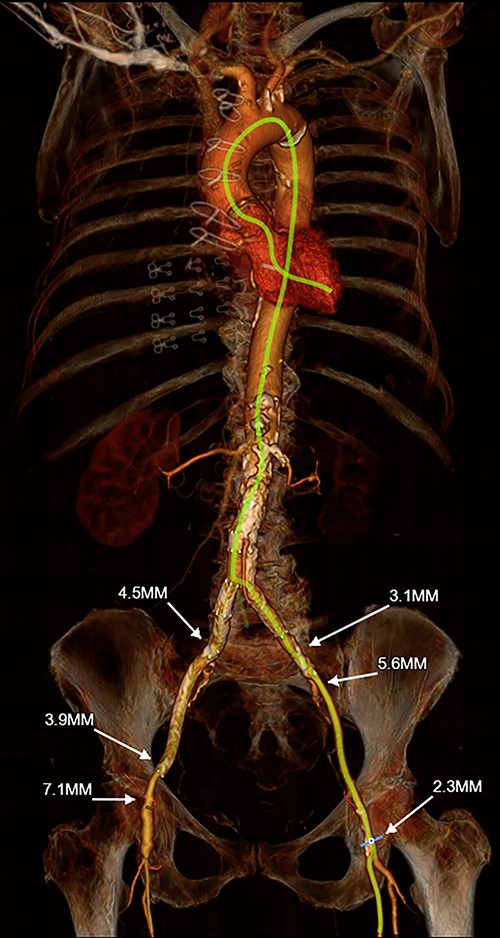

The patient is an 81-year-old woman with coronary artery disease status-post coronary artery bypass grafting; hypertension; hyperlipidemia; diabetes mellitus; bilateral carotid artery disease complicated by stroke; peripheral arterial disease complicated by celiac artery occlusion, superior mesenteric artery stenting and lower extremity claudication status-post bilateral iliac artery stenting; and newly symptomatic severe aortic stenosis. Subsequent TAVR evaluation including computed tomography (CT) angiography of the chest, abdomen and pelvis demonstrated extensive atherosclerotic disease of the bilateral iliofemoral system (with prohibitively small 2–3 mm right external iliac and left common femoral arteries), as well as extensive atherosclerosis of the bilateral axillary and subclavian arteries. Her innominate artery was of normal caliber and disease-free (Fig. 1). The patient’s Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS)-predicted risk of mortality for surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR) was 4%.

3-D reconstruction of Patient #1’s TAVR CT angiogram of the chest, abdomen and pelvis demonstrating prohibitively small iliofemoral arterial anatomy and heavily diseased bilateral subclavian arteries; the innominate artery is of normal caliber and is minimally diseased.

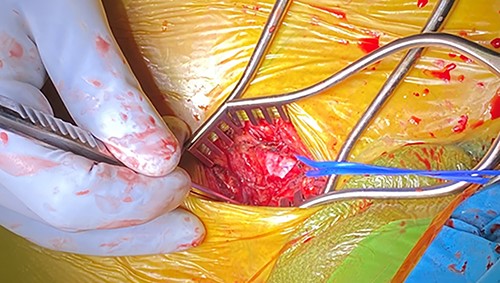

The patient was brought to the cardiac catheterization suite and placed under general endotracheal anesthesia. In addition to 5-French arterial access in the left common femoral artery and a 7-French left common femoral vein sheath, a 5 cm incision was made along the medial border of the right sternocleidomastoid muscle just superior to the sternal notch and the muscle was reflected laterally. The innominate artery was identified without separating the manubrium (Fig. 2). Systemic heparin was administered to achieve an activated clotting time (ACT) of 250 s; a 5–0 Prolene pursestring suture was then placed atop the anterior surface of the innominate artery, through which a 6-French sheath was then placed. An Amplatz extra-stiff wire (Cook Medical, Bloomington, IN, USA) was then advanced via this sheath into the left ventricle with a JR-4 catheter (Cordis, Hialeah, FL, USA). An 18-French Edwards Centitude delivery sheath (Edwards Lifesciences, Irvine, CA, USA) was next inserted overtop the Amplatz wire, through which a 26 mm Sapien S3 TAVR prosthesis (Edwards Lifesciences, Irvine, CA, USA) was deployed under a period of rapid ventricular pacing and simultaneous root aortography. Post-deployment transthoracic echocardiography and repeat aortography demonstrated trace aortic insufficiency. The 18-French sheath was removed from the innominate artery and its site was secured by tying the previously placed 5–0 Prolene pursestring stitch; the wound was closed in layers. The patient tolerated the procedure well and was discharged home the following day with marked improvement in her exertional symptoms; she remains well 9 months after TAVR.

Intra-operative photo illustrating the longitudinal incision overtop the medial aspect of the right sternocleidomastoid muscle; the blue vessel loop is encircled around the innominate artery.

Case 2

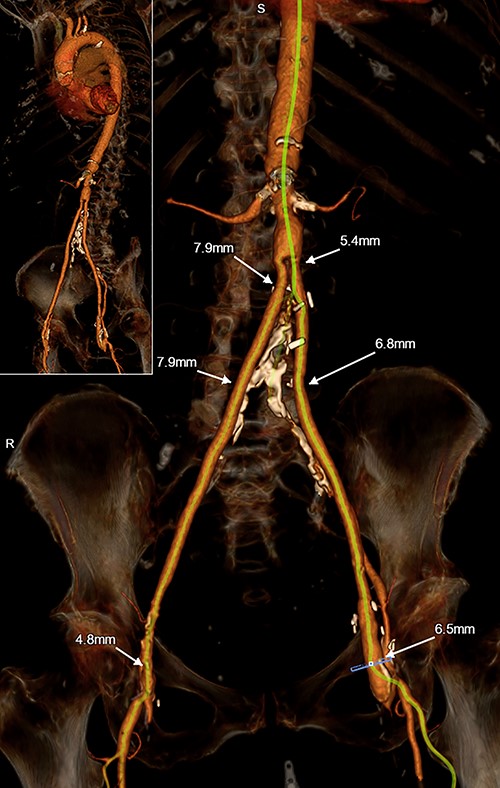

The patient is an 80-year-old woman with coronary artery disease status-post percutaneous coronary intervention, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes mellitus, aortoiliac occlusive disease status-post aortobifemoral bypass, peripheral arterial disease status-post bilateral femoral-popliteal bypasses, bilateral carotid artery disease and severe symptomatic aortic stenosis. CT angiography revealed extensive arterial disease including chronically occluded native iliac arteries with patent bypass grafts, stenoses of the bilateral subclavian arteries and tortuous, heavily calcified bilateral carotid arteries; the innominate artery was normal-appearing (Fig. 3). The patient’s STS-predicted risk of mortality for SAVR was 3.5%.

3-D reconstruction of Patient #2’s TAVR CT angiogram of the chest, abdomen and pelvis demonstrating hostile peripheral arterial anatomy, including an aortobifemoral bypass; the innominate artery is of normal caliber and is minimally diseased.

The patient was brought to the cardiac catheterization suite and placed under general endotracheal anesthesia. A 5-French sheath was placed into the left common femoral artery and a 7-French left common femoral vein sheath. A 5 cm incision was made along the medial border of the right sternocleidomastoid muscle just superior to the sternal notch and the muscle was reflected laterally. The innominate artery was identified without separating the manubrium and the patient was heparinized, achieving an ACT of 250 s. A 5–0 Prolene pursestring suture was placed along the anterior surface of the innominate artery, through which a 6-French sheath was then inserted. An Amplatz extra-stiff wire (Cook Medical, Bloomington, IN, USA) was then advanced via this sheath into the left ventricle using an MPA-2 catheter (Cordis, Hialeah, FL, USA). A 14-French Edwards eSheath (Edwards Lifesciences, Irvine, CA, USA) was next inserted overtop the Amplatz wire, through which a 26 mm Sapien Ultra TAVR prosthesis (Edwards Lifesciences, Irvine, CA, USA) was deployed under a period of rapid ventricular pacing and simultaneous root aortography. Post-deployment transthoracic echocardiography and repeat aortography demonstrated trace aortic regurgitation. The 14-French delivery sheath was removed from the innominate artery and its site was secured by tying the pursestring stitch; the incision was closed in layers. The patient tolerated the procedure well and was discharged home the following day. Her previous exertional symptoms remain resolved 3 months after TAVR.

DISCUSSION

TAVR has supplanted SAVR in increasing numbers of patients and is now recommended over SAVR for patients aged 80 years and older [1]. While advancements in TAVR-prosthesis and delivery-sheath designs now allow for percutaneous transfemoral arterial access in diseased femoral vessels that were previously too small for older iterations of this procedure, some patients’ peripheral arterial disease remains prohibitive for safe transfemoral, transaxillary, transcarotid or transcaval approaches. We believe that the above-described direct innominate artery technique is a safe and feasible alternative in these difficult cases and spares the morbidity of either transapical access or a more complex sternotomy.

The two cases presented above offer some insights into this approach to alternative access. In Case 1, the innominate artery was 8 mm in diameter and the ascending aorta was relatively short; hence, an 18-French sheath was used, as this allows for the deployment balloon to be preloaded within the TAVR prosthesis outside of the body. Conversely, in Case 2, the diameter of the innominate artery was 6 mm, so a 14-French expandable sheath was used to minimize the risk of fully occluding the innominate artery. This, however, requires the deployment balloon to be loaded into the TAVR valve after it has already been inserted into the body; in this case, in the ascending aorta. Moreover, if there are concerns about occluding the innominate artery, particularly when there is concomitant contralateral carotid disease, then other alternative access should be considered, such as direct aortic, transapical or transcaval approaches.

Accessing the innominate artery is only possible though a limited incision when the artery’s course is anterior and near midline; the artery must be relatively long with a late distal bifurcation between the right subclavian and right common carotid arteries. The innominate artery must be palpable above the sternal notch—otherwise an upper manubrial split may be necessary to gain full exposure of the artery. Other relative contraindications to direct innominate artery access include history of head/neck radiation and the presence of an in situ right internal mammary artery graft. This transinnominate artery approach also poses some logistical challenges in operator and fluoroscopy C-arm positioning.

Assuming the aforementioned requirements are satisfied, direct innominate artery access offers an additional, safe point of alternative access in TAVR.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

DISCLOSURES

No relevant disclosures.

Reference

Otto CM, Nishimura RA, Bonow RO, Carabello BA, Erwin JP, Gentile F et al.