-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Aihab Aboukheir-Aboukheir, Paloma M Lugo-Perez, Eduardo Colon-Melendez, Ivan Gonzalez-Cancel, Dev R Boodoodingh-Casiano, Recurrent chylopericardium in a patient with history of left leg sarcoma, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2022, Issue 5, May 2022, rjac245, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjac245

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Chylopericardium is a rare condition that is characterized by the presence of chyle in the pericardial space due to idiopathic (primary) or secondary causes. We present a 43-year-old female with hypothyroidism and left lower extremity sarcoma which were treated with resection and adjuvant chemoradiotherapy that was found with moderate pericardial effusion in surveillance tests. The patient was initially treated with tube thoracostomy and conservative management but presented with recurrence. Eventually, she was treated with left thoracotomy, ligation of the thoracic duct and pericardiectomy.

INTRODUCTION

Chylopericardium is a rare entity consisting of the accumulation of chylous fluid in the pericardial space [1]. First described in 1954 by Groves and Effler [2], the etiology of idiopathic chylopericardium is still unknown. Secondary chylopericardium has been reported in a patient with a lymphatic injury to the thoracic duct [3], tuberculosis, acute pancreatitis, Gorham disease and lymphatic anomaly, such as Kaposiform Lymphangiomatosis [4]. Even most patients with chylopericardium are asymptomatic; some may present with tamponade or pericarditis [5]. Management consists of dietary medium-chain triglycerides (MCT), pericardiocentesis, tube pericardiotomy, pericardial window and ligation of the thoracic duct. We present a case of recurrent chylopericardium and the surgical interventions performed.

CASE REPORT

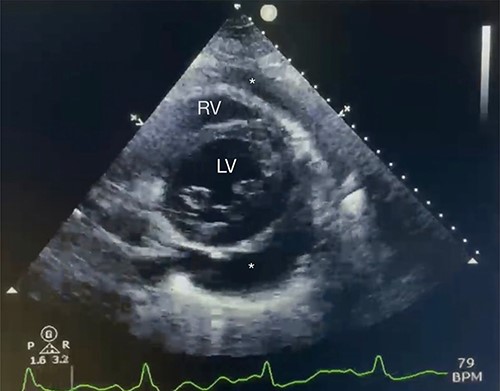

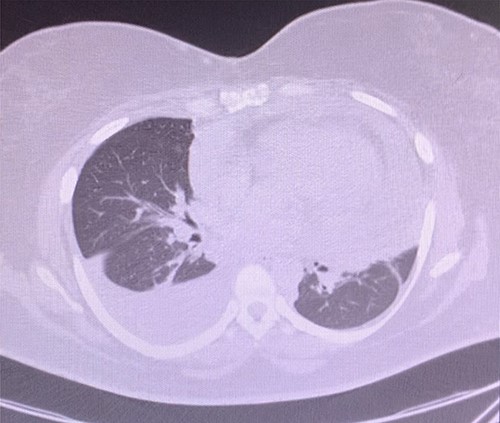

A 43-year-old woman with hypothyroidism and left lower extremity sarcoma that was treated with wide excision, and chemoradiotherapy treated with Doxorubicin, was performing routine screening with the oncologist which included a positron emission tomography/computed tomography (CT) scan, in which two small hypermetabolic nodules in the right upper lobe of the lung and a moderate to large pericardial effusion were found, effusion confirmed with an echocardiogram (Fig. 1). Upon findings, patient was sent to ER due to high suspicion of metastasis due to sarcoma history. She denied cough, shortness of breath, chest pain, palpitation, syncope or diaphoresis and related unintentional weight loss of 30 pounds in the last 3 months. Upon evaluation, patient was found with stable signs and there were no findings of pericardial tamponade. Chest CT scan was sent for further evaluation (Fig. 2).

Echocardiography with moderate pericardial effusion: subcostal 2 chamber echocardiography view demonstrating * = pericardial effusion, RV = right ventricle and LV = left ventricle.

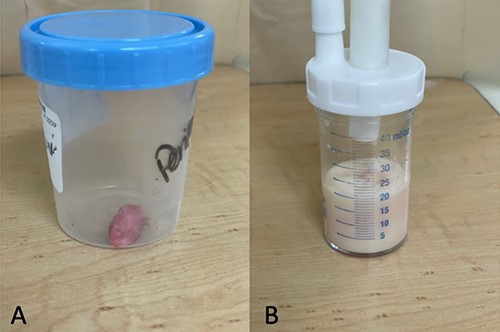

Due to a malignant sarcoma history, the patient was referred to cardiothoracic surgery for pericardial window and pericardial biopsy. Upon performing a subxiphoid pericardial window and entering the pericardial sac, 600 ml of milky fluid was evacuated (Fig. 3); a pericardial window was performed, a biopsy was obtained, fluid was analyzed and a chest tube drain was left in place. The pericardial fluid analysis yielded a high triglyceride count (2952 mg/dl) and a cholesterol-triglycerides ratio that was <1 (Table 1).

Pericardial biopsy and fluid: labeled as biopsy (A) and fluid (B).

| Fluid color . | White . |

|---|---|

| Cell count (lymphocytes) | 83.7% |

| Glucose | 87 mg/dl |

| Protein | 4.2 mg/dl |

| Total cholesterol | 159 mg/dl |

| Triglycerides | 2952 mg/dl |

| Cholesterol/triglycerides ratio | 0.05 |

| Gram stain | Negative |

| Fluid culture | Negative |

| Fluid color . | White . |

|---|---|

| Cell count (lymphocytes) | 83.7% |

| Glucose | 87 mg/dl |

| Protein | 4.2 mg/dl |

| Total cholesterol | 159 mg/dl |

| Triglycerides | 2952 mg/dl |

| Cholesterol/triglycerides ratio | 0.05 |

| Gram stain | Negative |

| Fluid culture | Negative |

| Fluid color . | White . |

|---|---|

| Cell count (lymphocytes) | 83.7% |

| Glucose | 87 mg/dl |

| Protein | 4.2 mg/dl |

| Total cholesterol | 159 mg/dl |

| Triglycerides | 2952 mg/dl |

| Cholesterol/triglycerides ratio | 0.05 |

| Gram stain | Negative |

| Fluid culture | Negative |

| Fluid color . | White . |

|---|---|

| Cell count (lymphocytes) | 83.7% |

| Glucose | 87 mg/dl |

| Protein | 4.2 mg/dl |

| Total cholesterol | 159 mg/dl |

| Triglycerides | 2952 mg/dl |

| Cholesterol/triglycerides ratio | 0.05 |

| Gram stain | Negative |

| Fluid culture | Negative |

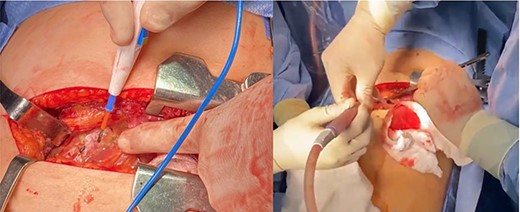

The patient was treated conservatively with MCT and a low-fat diet. Chest tube output was measured and was discontinued after low output; the patient was discharged home with follow-up at the outpatient clinic. One week after discharge, patient returned with dyspnea, and upon evaluation, was found with recurrent moderate pericardial effusion. Pericardial biopsy pathology was evaluated and no malignancy was found. At this time, the patient was taken to the operating room for left lateral thoracotomy (Fig. 4) with subtotal pericardiectomy and ligation of the thoracic duct with findings of 1200 ml of chylopericardium intra-operative, chest tube left in place.

DISCUSSION

Idiopathic chylopericardium is an uncommon condition diagnosed after excluding other etiologies that could cause pericardial effusion. In our patient, the primary suspicion was a malignant effusion due to left leg sarcoma history but was essentially ruled out due to the pathologic biopsy of pericardial sac, demonstrating dense fibroconnective tissue with no malignancy, and fluid cytology also with no malignant cells. Possible mechanisms of accumulation of chylous include damage to lymphatic channels which cause efflux of chyle from the thoracic duct to pericardial space and elevated pressure in the thoracic duct which may occur in lymphangiectasia [5, 6]. There are no unique features on echocardiogram or chest X-ray film which could predict the diagnosis of chylous pericardial effusion [7]. First-line diagnostic evaluation to find the cause was echocardiography and aspiration of pericardial fluid followed by CT or magnetic resonance imaging [8]. Upon analysis of pericardial fluid diagnosis, analysis reaches sensitivity and specificity of 100% if two of the following are found: triglycerides level of >500 mg/dl, cholesterol/triglycerides ratio < 1 and negative cultures with a lymphocytic predominance (Dib). Conservative management has been reported, but the failure rate may reach 57%. In patients not willing to undergo surgical intervention, chemical pericardiodesis has been reported [6]. Another medical treatment besides total parenteral nutrition (TPN) is the use of somatostatin treatment; adding somatostatin to TPN decreases drain loss time, duration of the pericardial drain and length of hospital stay compared with other published data with the use of somatostatin [9]. In our patient, due to reaccumulating of fluid, a left lateral thoracotomy was used to access the thoracic duct and to perform low ligation and pericardial window, a procedure described as the best method to avoid recurrence [5].

Idiopathic chylopericardium is a benign disease, but if left untreated, complications could be fatal; in our experience with this case, a combination of echocardiography, CT scan and pericardial window with an analysis of pericardial fluid is a very effective and useful diagnostic tool. The patient should be followed due to the risk of recurrence and the most important complication of this pathology is the development of constrictive pericarditis [7]. Due to pericardial effusion, patient developed heart failure with reduced ejection fraction and was placed with life vest. After 1 month of clinical follow-up, the patient was symptom-free and with a normal chest X-ray. At 9-month clinical follow-up, the patient recovered her ejection fraction with optimal medical management and the echocardiogram was free of recurrent pericardial effusion.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

FUNDING

None.