-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Jason Silvers, Shaili Dixit, Khea Tan, Rachel Masia, Abimbola Pratt, Constantine Bulauitan, Dena Arumugam, Seth Kipnis, A novel presentation of alcohol-induced gastric necrosis: a case report, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2022, Issue 12, December 2022, rjac601, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjac601

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Acute gastric necrosis is a rare condition with unknown pathogenesis. Existing literature describes acute esophageal necrosis as a result of excessive alcohol use; however, it is more difficult to find literature on alcohol-induced gastric necrosis. This condition may present with epigastric tenderness, vomiting or diarrhea with findings of pneumoperitoneum, gastric pneumatosis and portal venous gas on computed tomography. These patients can have complications such as septic shock, peritonitis and death. In this case report, we discuss a patient with a history of alcohol abuse who presented with acute gastric necrosis. On endoscopy, this patient was found to have a black necrotic gastric fundus and unusual erythematous changes to the mucosa. Prior research has identified other findings of patchy or diffuse circumferential black pigmentation of esophageal mucosa in patients with alcohol-induced esophageal necrosis, otherwise known as black esophagus. This case report aims to describe this novel presentation of alcohol-induced gastric necrosis.

INTRODUCTION

In this case report, we discuss a case of alcohol-induced gastric necrosis. Until now, only literature on alcohol-induced esophageal necrosis has been available. We discuss the presentation and potential etiologies of this condition, as well as surgical treatment.

CASE REPORT

The patient was a 58-year-old male with a history of alcohol abuse, type II diabetes mellitus with peripheral neuropathy of his bilateral lower extremities, hypertension, hyperlipidemia and stroke with residual left-sided weakness. His chief complaint on presentation from his assisted living facility was abdominal pain in the left upper quadrant and diarrhea, with dark stools. The pain was constant and dull, with 10/10 intensity. His pain worsened with movement, but not with food or drink. Additional symptoms included diaphoresis and dyspnea. He denied nausea, vomiting, hematochezia, chest pain, fever or chills.

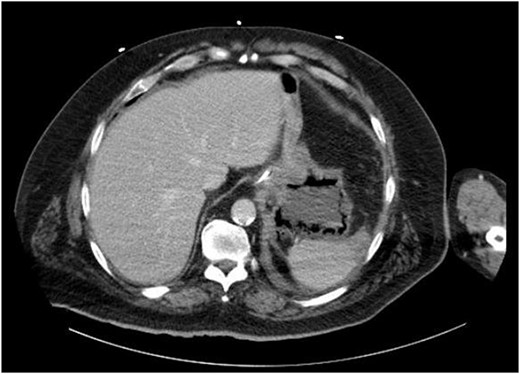

On evaluation, the patient was afebrile, tachycardic to 107 bpm, with BP 112/63 and RR 21. On exam, he appeared diaphoretic and had left upper quadrant tenderness without rebound or guarding. He was otherwise alert and oriented. His white blood cell count was 22.5 with 13.1 bands, and lactate of 6.2, which improved with IV fluid resuscitation. Computed tomography (CT) abdomen and pelvis demonstrated pneumatosis of the proximal gastric wall (Fig. 1), and mild portal venous gas. He was started on antibiotics and antifungals; a nasogastric tube was placed for decompression, and he was started on parenteral nutrition; however, he failed to improve clinically, with continued abdominal pain and tenderness, and persistent tachycardia. A repeat CT after 5 days of treatment redemonstrated gastric wall pneumatosis (Fig. 2), though with resolution of the portal venous gas.

Repeat CT of the abdomen and pelvis: decompression of the stomach with persistent gastric pneumatosis.

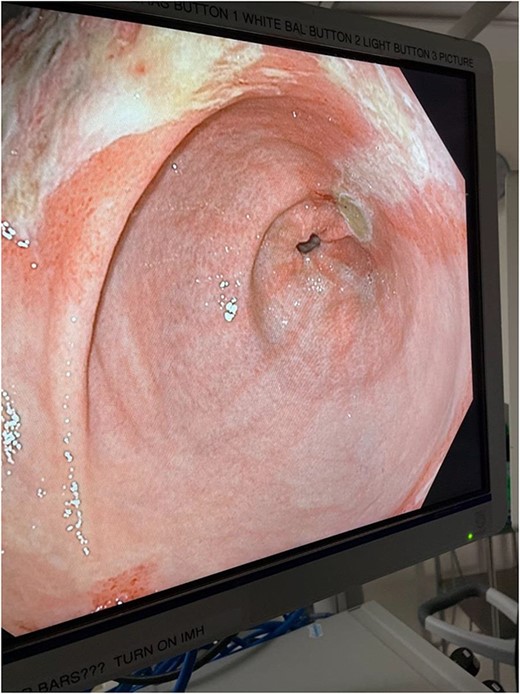

The decision was made to take the patient to the operating room. He underwent diagnostic laparoscopy, which showed a normal gastric antrum; however, on further inspection, a hemorrhagic and inflamed area of stomach was seen proximally at the fundus on the underside of the diaphragm. Next, esophagogastroduodenoscopy was performed, which demonstrated a large black necrotic area in the fundus (Fig. 3), as well as inflammation throughout the rest of the gastric body (Figs 4 and 5). At this point, malignancy could not be ruled out, so the operation was converted to open with a subxiphoid to supraumbilical midline incision. Once in the abdomen and able to further inspect the stomach, the frankly necrotic portion of fundus was noted to be adhered to the underside of the diaphragm and a contained purulent fluid collection was encountered in this area and drained. A partial gastrectomy was then undertaken in similar fashion to a sleeve gastrectomy. The lesser sac was entered and the stomach mobilized along the greater curvature with an energy device up through the short gastrics. A stapler was used to resect the entire necrotic portion of stomach from the midbody to the angle of His. Frozen sections were sent which were negative for malignancy. The remaining stomach was inspected for signs of malignancy, but none were found. For these reasons, no further resection was done. The entire staple line was imbricated due to concern for an ischemic etiology for the patient’s disease process, and two drains were left—one anterior and one posterior to the staple line. Final pathology showed prominent gangrenous necrosis, ulcer and acute necro-inflammatory exudate. Most of the specimen had no viable gastric mucosa, and no malignancy was found.

Intraoperative endoscopic image: inflammatory changes of gastric mucosa in midbody of stomach.

Intraoperative endoscopic image: inflammatory changes of gastric mucosa in antrum of stomach.

Post-operatively, TPN and NG tube decompression were continued. The patient became septic following the operation, requiring a stay in SICU, pressors and several days of intubation. He was resuscitated adequately and treated with antibiotics and antifungals, until he improved clinically and was extubated. He underwent an oral contrast CT on post-operative Day 7, which showed only post-operative changes without signs of contrast extravasation or ischemic changes. The patient’s diet was advanced slowly as tolerated to full liquids by post-op Day 12 and TPN was discontinued. He was discharged to a rehab facility, with education on diet and alcohol cessation.

DISCUSSION

Stomach is one of the most well-vascularized organs in the body. The left and right gastric arteries provide blood to the lesser curvature, and the left and right gastroepiploic arteries provide blood to the greater curvature. Additional blood is supplied to the proximal portion of the stomach by the short gastric and inferior phrenic arteries. Because of the various origins of these arteries and their anastomotic nature, gastric ischemia is rare [1]. This is why the presentation of this case is so unusual.

Cases of esophageal necrosis, termed ‘black esophagus’, have been described, and have been attributed to alcohol abuse. Endo et al. [2] hypothesized that acute esophageal necrosis is caused by lactic acidosis secondary to alcohol ingestion, which in turn can lead to poor perfusion. Additionally, ethanol, its metabolite acetaldehyde and other fermentation products can cause direct damage to the mucosa and increase production of gastric secretions [3, 4], all of which could contribute to gastric necrosis. Direct mucosal damage from these substances in turn makes gastric mucosa more susceptible to damage from gastric acid, bile and other digestive enzymes [5].

Lazaratos et al. [6] showed via rat model that high ethanol intake can increase plasma levels of endothelin-1 (ET-1), as well as decrease plasma levels of nitric oxide (NO) and prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), exacerbating the direct mucosal damage of ethanol and its metabolites. NO and PGE2 contribute to gastric mucosal protection and the ability to repair mucosal damage [7]. ET-1 is a potent vasoconstrictor of gastric mucosal circulation, compounding effects of the decrease in NO and PGE2 [6].

In conclusion, we seek to offer a potentially novel presentation of alcohol abuse, in the form of acute gastric necrosis. The exact pathophysiology of this patient’s presentation is ultimately unknown; however, the combination of the deleterious effects of ethanol and its metabolites, elevated plasma ET-1 and decreased NO and PGE2 levels, as well as global hypoperfusion of the stomach secondary to lactic acidosis likely factor strongly into this disease process. Further research should be done to investigate the pathophysiology of acute gastric necrosis in the setting of alcohol abuse.

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient’s proxy for publication of this case report and accompanying images.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this article.

FUNDING

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.