-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Simone Oliver Senica, Paolo Gasparella, Ksenija Soldatenkova, Lauris Smits, Zane Ābola, Cardiac perforation during minimally invasive repair of pectus excavatum: a rare complication, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2022, Issue 11, November 2022, rjac538, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjac538

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Life-threatening complications (LTCs) and negative results of surgical treatments often go unreported. Minimally invasive repair of pectus excavatum (MIRPE) represents a procedure with a low incidence of adverse outcomes. However, 15 potentially fatal cases of MIRPE-related heart injury have been published. We report a case of cardiac perforation (CP) during MIRPE. A 12-year-old female was admitted for elective repair of a severe asymmetric pectus excavatum. Preoperative computed tomography showed a Haller index of 4.9. MIRPE was performed under bilateral video-assisted thoracoscopy. After the placement of the pectus bar, cardiac arrhythmias, hypotension and bilateral hemothorax occurred. Emergency thoracotomy without pectus bar removal showed CP. The wound sites were repaired and the pectus bar was eventually successfully implanted. The patient was discharged on postoperative day 11. After 10 months, she remains asymptomatic. Reporting rare complications is essential for accurate calculations of the true prevalence of LTCs, maintaining high alertness in pediatric surgeons.

INTRODUCTION

Pectus excavatum (PE) is the most common thoracic wall deformity with an incidence between 0.1 and 0.8% [1]. Since its introduction in 1998, the minimally invasive repair of pectus excavatum (MIRPE), or Nuss procedure, has become the standard procedure for surgical correction of PE. Although several modifications have increased the safety of MIRPE, this technique still carries a higher risk of adverse outcomes than the open Ravitch approach [2]. A rare but life-threatening complication (LTC) is cardiac perforation (CP), which has been reported 15 times in association with MIRPE, according to the current literature [3–12].

We describe a case of CP following Nuss procedure, to remind surgeons not to underestimate the potentially fatal complications of a minimally invasive procedure. We also want to emphasize the importance of reporting LTCs and negative surgical experiences to provide additional data for a better estimation of their prevalence.

CASE REPORT

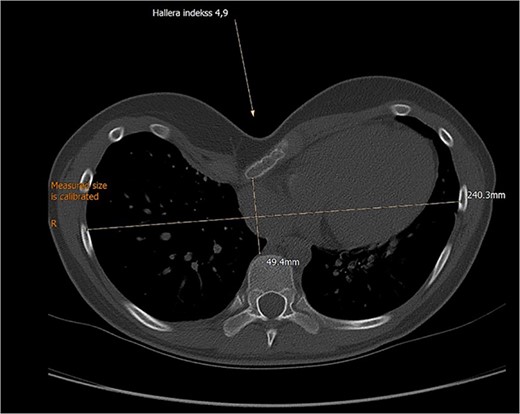

A 12-year-old female patient with severe PE was admitted for an elective MIRPE. Upon exertion, she complained of shortness of breath and feeling of pressure in the chest. Cosmetic concerns were expressed by the patient and her family. Inspection and palpation of the thoracic region revealed a deep conical depression of the chest wall. Preoperative electrocardiogram, echocardiography and pulmonary function tests at rest were normal. Computed tomography (CT) showed a Haller index 4.9, indicating cardiac displacement to the left and rotation of the sternum to the right by 35° (Fig. 1).

Preoperative computed tomography demonstrating severe pectus excavatum with Haller’s index 4.9.

The operation was performed under general anesthesia and double lumen endotracheal intubation. By bilateral thoracoscopy, we visualized a deep protrusion of the sternum from both pleural cavities and the heart prominently deviated to the left. The pectus dissector was introduced along the anterior thoracic wall and retrosternally from the right to the left side. Subsequently, we inserted the pectus bar from the right to the left and rotated it. On rotation of the pectus bar, cardiac arrhythmias and hypotension were observed. The patient’s condition improved slightly by derotating the bar. However, bilateral hemothorax was thoracoscopically detected.

Upon suspicion of heart injury, the metal bar was left in place. Cardiac surgeons performed an emergency sternotomy with a left anterior thoracotomy. The metal bar entered the heart from the right atrium, passed through the anterior part of the interventricular wall and exited the myocardium from the anterior left ventricle wall. After bar removal, the injuries were repaired with interrupted nonabsorbable sutures. The bleeding was managed through massive blood transfusions (3782 ml). Eventually, the patient was hemodynamically stable and the pectus bar was correctly implanted. After 6 days in the ICU, we discharged the patient from the hospital on postoperative day 11.

Ten months after surgery, the patient is asymptomatic with a noticeable PE correction (Fig. 2). Bar removal is planned 3 years after primary repair in a cardiothoracic surgical setting.

Postoperative chest X-ray showing the correct positioning of the bar.

DISCUSSION

We share the sixteenth case of a CP associated with MIRPE to maintain high the awareness of the LTCs of this minimally invasive procedure.

The incidence of potentially fatal complications following MIRPE is unknown, as they are rare and often unreported [2]. MIRPE can affect myocardial function and structure, potentially leading to persistent arrhythmias or pericarditis [2]. However, the most feared complications are iatrogenic cardiac intraoperative injuries, including CP [6].

According to the literature, CP has occurred in different circumstances associated with MIRPE (Table 1). More than half of the cases (11/16), including ours, happened during initial PE repair and 3/16 during bar removal procedures. Out of 16, 1 had a previous Ravitch repair, whereas 3 had a history of open cardiac surgery [6, 13]. The most frequent injury sites (12/16 cases) were the right atrium or ventricle, or both. The 16 affected patients had different outcomes: 11 completely recovered, 2 suffered lifelong disability and 3 unfortunately died. All cases were treated with aggressive circulatory resuscitation and surgical repair of the injury sites. [6]. In our case, leaving the metal bar in place created a tamponade effect that slowed the bleeding and allowed us to manage CP without extracorporeal circulation.

| N. | Procedure | Age | Sex | Specific features | CP cause / mechanism | Injury site | Outcome | Author |

| 1 | Initial repair | 8 | M | Not thoracoscopy | Vascular clamp | RA and RV | Recovery | Moss et al., 2001 |

| 2 | Initial repair; from MIRPE to Ravitch | 17 | M | PA to anterior thoracic wall | Pectus bar | RA and RV | Death | Gips et al., 2007 |

| 3 | Initial repair | N/A | N/A | Marked sternal compression | Introducer behind very deep sternum | Unspecified | Recovery | Castellani et al., 2008 |

| 4 | Initial repair | 16 | M | N/A | During introducer insertion | Pericardium | Recovery | Belcher et al., 2008 |

| 5 | Initial repair | 14 | M | Extreme PE severity | Pectus dissector | RA and TV | Disability | Bouchard et al., 2009 |

| 6 | MIRPE after Ravitch repair | 18 | M | HMRR; distorted anatomy; PA | Bleeding noted during introducer removal | RA and RV | Disability | Bouchard et al., 2009 |

| 7 | MIRPE after open cardiac surgery | 11 | M | History of cardiac surgery; marked sternal compression; PA | Dissector tip through the RV | RV | Recovery | Bouchard et al., 2009 |

| 8 | Bar removal | 17 | M | Chronic pain after initial repair; PA | Adhesions tearing the pericardium | LV | Death | Bouchard et al., 2009 |

| 9 | Bar removal | 20 | F | History of cardiac surgery; PA | CP by bar during removal | RV (2 sites) | Recovery | Haecker et al., 2009 |

| 10 | Initial repair | 18 | M | N/A | Retrosternal dissection by introducer | RA and RV | Recovery | Becmeur et al., 2011 |

| 11 | Bar removal | 13 | F | N/A | CP by bar during removal | RV | Recovery | Sakakibara et al., 2013 |

| 12 | Initial repair | 16 | M | N/A | N/A | RA and RV | Death | Schaarschmidt et al., 2013 |

| 13 | Initial repair | 16 | F | N/A | During introducer insertion | RA | Recovery | Rygl et al., 2013 |

| 14 | Initial repair | N/A | N/A | History of cardiac surgery | During introducer insertion | RV | Recovery | Obermeyer et al., 2021 |

| 15 | Initial repair | N/A | N/A | History of cardiac surgery | Dense retrosternal adhesions | RA | Recovery | Obermeyer et al., 2021 |

| 16 | Initial repair | 14 | F | N/A | During introducer insertion | RA | Recovery | Current report, 2022 |

| N. | Procedure | Age | Sex | Specific features | CP cause / mechanism | Injury site | Outcome | Author |

| 1 | Initial repair | 8 | M | Not thoracoscopy | Vascular clamp | RA and RV | Recovery | Moss et al., 2001 |

| 2 | Initial repair; from MIRPE to Ravitch | 17 | M | PA to anterior thoracic wall | Pectus bar | RA and RV | Death | Gips et al., 2007 |

| 3 | Initial repair | N/A | N/A | Marked sternal compression | Introducer behind very deep sternum | Unspecified | Recovery | Castellani et al., 2008 |

| 4 | Initial repair | 16 | M | N/A | During introducer insertion | Pericardium | Recovery | Belcher et al., 2008 |

| 5 | Initial repair | 14 | M | Extreme PE severity | Pectus dissector | RA and TV | Disability | Bouchard et al., 2009 |

| 6 | MIRPE after Ravitch repair | 18 | M | HMRR; distorted anatomy; PA | Bleeding noted during introducer removal | RA and RV | Disability | Bouchard et al., 2009 |

| 7 | MIRPE after open cardiac surgery | 11 | M | History of cardiac surgery; marked sternal compression; PA | Dissector tip through the RV | RV | Recovery | Bouchard et al., 2009 |

| 8 | Bar removal | 17 | M | Chronic pain after initial repair; PA | Adhesions tearing the pericardium | LV | Death | Bouchard et al., 2009 |

| 9 | Bar removal | 20 | F | History of cardiac surgery; PA | CP by bar during removal | RV (2 sites) | Recovery | Haecker et al., 2009 |

| 10 | Initial repair | 18 | M | N/A | Retrosternal dissection by introducer | RA and RV | Recovery | Becmeur et al., 2011 |

| 11 | Bar removal | 13 | F | N/A | CP by bar during removal | RV | Recovery | Sakakibara et al., 2013 |

| 12 | Initial repair | 16 | M | N/A | N/A | RA and RV | Death | Schaarschmidt et al., 2013 |

| 13 | Initial repair | 16 | F | N/A | During introducer insertion | RA | Recovery | Rygl et al., 2013 |

| 14 | Initial repair | N/A | N/A | History of cardiac surgery | During introducer insertion | RV | Recovery | Obermeyer et al., 2021 |

| 15 | Initial repair | N/A | N/A | History of cardiac surgery | Dense retrosternal adhesions | RA | Recovery | Obermeyer et al., 2021 |

| 16 | Initial repair | 14 | F | N/A | During introducer insertion | RA | Recovery | Current report, 2022 |

CP – cardiac perforation; F – female; HMRR – highly modified Ravitch repair; LV – left ventricle; M – male; PA – pericardial adhesion; RA – right atrium; RV – right ventricle; TV – tricuspid valve

| N. | Procedure | Age | Sex | Specific features | CP cause / mechanism | Injury site | Outcome | Author |

| 1 | Initial repair | 8 | M | Not thoracoscopy | Vascular clamp | RA and RV | Recovery | Moss et al., 2001 |

| 2 | Initial repair; from MIRPE to Ravitch | 17 | M | PA to anterior thoracic wall | Pectus bar | RA and RV | Death | Gips et al., 2007 |

| 3 | Initial repair | N/A | N/A | Marked sternal compression | Introducer behind very deep sternum | Unspecified | Recovery | Castellani et al., 2008 |

| 4 | Initial repair | 16 | M | N/A | During introducer insertion | Pericardium | Recovery | Belcher et al., 2008 |

| 5 | Initial repair | 14 | M | Extreme PE severity | Pectus dissector | RA and TV | Disability | Bouchard et al., 2009 |

| 6 | MIRPE after Ravitch repair | 18 | M | HMRR; distorted anatomy; PA | Bleeding noted during introducer removal | RA and RV | Disability | Bouchard et al., 2009 |

| 7 | MIRPE after open cardiac surgery | 11 | M | History of cardiac surgery; marked sternal compression; PA | Dissector tip through the RV | RV | Recovery | Bouchard et al., 2009 |

| 8 | Bar removal | 17 | M | Chronic pain after initial repair; PA | Adhesions tearing the pericardium | LV | Death | Bouchard et al., 2009 |

| 9 | Bar removal | 20 | F | History of cardiac surgery; PA | CP by bar during removal | RV (2 sites) | Recovery | Haecker et al., 2009 |

| 10 | Initial repair | 18 | M | N/A | Retrosternal dissection by introducer | RA and RV | Recovery | Becmeur et al., 2011 |

| 11 | Bar removal | 13 | F | N/A | CP by bar during removal | RV | Recovery | Sakakibara et al., 2013 |

| 12 | Initial repair | 16 | M | N/A | N/A | RA and RV | Death | Schaarschmidt et al., 2013 |

| 13 | Initial repair | 16 | F | N/A | During introducer insertion | RA | Recovery | Rygl et al., 2013 |

| 14 | Initial repair | N/A | N/A | History of cardiac surgery | During introducer insertion | RV | Recovery | Obermeyer et al., 2021 |

| 15 | Initial repair | N/A | N/A | History of cardiac surgery | Dense retrosternal adhesions | RA | Recovery | Obermeyer et al., 2021 |

| 16 | Initial repair | 14 | F | N/A | During introducer insertion | RA | Recovery | Current report, 2022 |

| N. | Procedure | Age | Sex | Specific features | CP cause / mechanism | Injury site | Outcome | Author |

| 1 | Initial repair | 8 | M | Not thoracoscopy | Vascular clamp | RA and RV | Recovery | Moss et al., 2001 |

| 2 | Initial repair; from MIRPE to Ravitch | 17 | M | PA to anterior thoracic wall | Pectus bar | RA and RV | Death | Gips et al., 2007 |

| 3 | Initial repair | N/A | N/A | Marked sternal compression | Introducer behind very deep sternum | Unspecified | Recovery | Castellani et al., 2008 |

| 4 | Initial repair | 16 | M | N/A | During introducer insertion | Pericardium | Recovery | Belcher et al., 2008 |

| 5 | Initial repair | 14 | M | Extreme PE severity | Pectus dissector | RA and TV | Disability | Bouchard et al., 2009 |

| 6 | MIRPE after Ravitch repair | 18 | M | HMRR; distorted anatomy; PA | Bleeding noted during introducer removal | RA and RV | Disability | Bouchard et al., 2009 |

| 7 | MIRPE after open cardiac surgery | 11 | M | History of cardiac surgery; marked sternal compression; PA | Dissector tip through the RV | RV | Recovery | Bouchard et al., 2009 |

| 8 | Bar removal | 17 | M | Chronic pain after initial repair; PA | Adhesions tearing the pericardium | LV | Death | Bouchard et al., 2009 |

| 9 | Bar removal | 20 | F | History of cardiac surgery; PA | CP by bar during removal | RV (2 sites) | Recovery | Haecker et al., 2009 |

| 10 | Initial repair | 18 | M | N/A | Retrosternal dissection by introducer | RA and RV | Recovery | Becmeur et al., 2011 |

| 11 | Bar removal | 13 | F | N/A | CP by bar during removal | RV | Recovery | Sakakibara et al., 2013 |

| 12 | Initial repair | 16 | M | N/A | N/A | RA and RV | Death | Schaarschmidt et al., 2013 |

| 13 | Initial repair | 16 | F | N/A | During introducer insertion | RA | Recovery | Rygl et al., 2013 |

| 14 | Initial repair | N/A | N/A | History of cardiac surgery | During introducer insertion | RV | Recovery | Obermeyer et al., 2021 |

| 15 | Initial repair | N/A | N/A | History of cardiac surgery | Dense retrosternal adhesions | RA | Recovery | Obermeyer et al., 2021 |

| 16 | Initial repair | 14 | F | N/A | During introducer insertion | RA | Recovery | Current report, 2022 |

CP – cardiac perforation; F – female; HMRR – highly modified Ravitch repair; LV – left ventricle; M – male; PA – pericardial adhesion; RA – right atrium; RV – right ventricle; TV – tricuspid valve

In 2008, Nuss published a report about his 20-year experience with MIRPE, where CP never occurred [14]. Due to its frequent negative outcomes, we hypothesize that this complication often goes unreported. In 2018, Hebra et al. indicated that the number of unreported cases of CP (15) during MIRPE is higher than the number of reported cases (13) [2].

Several technique- or patient-dependent factors are associated with the occurrence of complications during or after the Nuss procedure. Some authors consider the surgeon’s lack of experience an important risk factor [9]. However, a recent study suggested that after a proctoring period of 10 surgeries, the complication rate did not decrease significantly for surgeons performing at least one MIRPE every 35 days. In our department, this procedure was introduced in 2002, and two dedicated surgeons perform around 30–35 Nuss operations each year. Factors that do not depend on the surgeon and predispose to complications after MIRPE are age above 16 years, history of previous thoracic surgery, degree of PE severity, major postoperative bar displacement, chronic pain after MIRPE, infection and/or pericarditis, and significant bleeding during bar removal [2, 4]. The high degree of severity (HI = 4.9) contributed to CP in our patient.

Over the years, several modifications have improved results and reduced the risk of LTCs, such as sternal elevation, vacuum bell and subxiphoid handheld hook [13]. In our case, bilateral thoracoscopy allowed visualization of the introducer’s tip throughout the procedure. We do not routinely adopt techniques to elevate the sternum because, in our experience, video assistance provides enough support for a safe retrosternal dissection.

Rare complications such as CP often go unreported, although sharing them is a good practice to facilitate a more precise estimation of their incidence [15]. Surgeons should not underestimate the risk of LTCs following minimally invasive procedures. Furthermore, awareness of potentially fatal adverse outcomes can endorse the necessity of performing the Nuss procedure in a cardiosurgical setting.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

FUNDING

None.