-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Ruben D Salas-Parra, Genevieve Hattingh, Karlie R Shumway, Kathryn Esposito, William Lois, Daniel T Farkas, Cholecystocolonic fistula: two different presentations of this rare complication of gallstones, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2022, Issue 11, November 2022, rjac520, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjac520

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Cholecystocolonic fistulas (CCF) are a rare but significant complication of biliary disease, frequently presenting as gallstone ileus. Although there is no one agreed-upon procedure, enterolithotomy appears to be the initial treatment of choice; with a subsequent cholecystectomy performed ~4–8 weeks later. Alternatively, a patient may undergo a single-stage procedure, at which time an enterolithotomy, cholecystectomy and fistula closure are performed. Herein, we describe two patients with chronic cholecystitis and subsequent development of CCF with differing presentations. We report the clinical, radiographic and intraoperative findings and discuss the surgical treatment options for each patient, respectively.

INTRODUCTION

Cholecystocolonic fistulas (CCF) typically present as gallstone ileus. They comprise roughly 8–26% of all cholecystoenteric fistulas, as compared with cholecystoduodenal fistulas (75%). Currently, a consensus on treatment for CCF does not exist, however, many reports [1–4] emphasize that the management of CCF ultimately depends on the severity of the presentation. This report describes two cases of chronic cholecystitis with CCF, each with a different clinical presentation. One presented with an acute large bowel obstruction, and the other presented as chronic inflammation mimicking a malignant hepatic flexure colonic mass during an elective cholecystectomy.

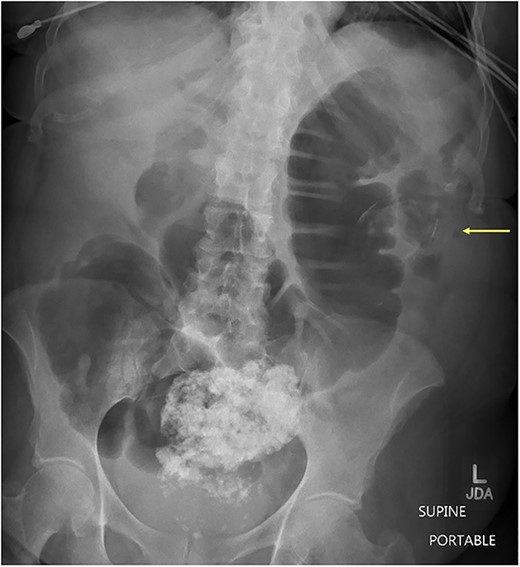

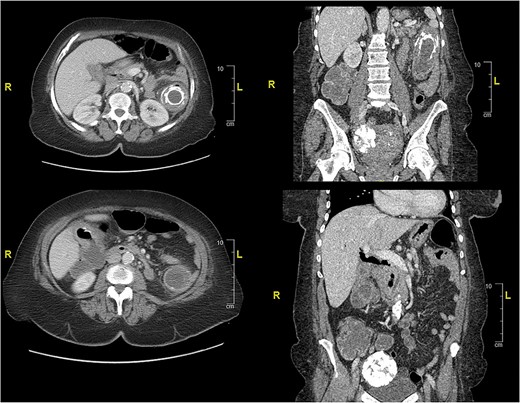

Case presentation # 1: An 80-year-old female with congestive heart failure and hypertension, presented to the emergency room with 4 days of diffuse abdominal pain associated with nausea, vomiting and anorexia. She was hemodynamically stable upon presentation, with upper abdominal tenderness on exam. Initial imaging (Figs 1 and 2) was obtained, showing a CCF with large bowel obstruction caused by an 8-cm gallstone in the descending colon. The patient was taken to the operating room for an exploratory laparotomy, where upon inspection a large gallstone in the descending colon and a fistulous communication between the gallbladder and hepatic flexure of the colon were noted. Takedown of the fistula was attempted, however because of extensive colonic involvement a decision was made to perform a right hemicolectomy with primary anastomosis, as well as a partial cholecystectomy at the level of infundibulum due to chronic inflammation and thickening of the gallbladder. The gallstone was taken out with the specimen (Fig. 3). The postoperative course was significant for exacerbation of heart failure, but ultimately, she was discharged home upon successful tolerance of a regular diet with return of bowel function.

Supine abdominal x-ray showing colonic dilation secondary to large enterolith within the descending colon. (Arrow pointing enterolith).

CT of abdomen and pelvis showing an inflamed gallbladder with fistulous communication within the hepatic flexure of the colon. Large descending colon enterolith (4.5 × 4.3 × 8.0 cm). Apparent pneumobilia.

Operative specimen showing the segment of the colon resected with the fistula identified and the large enterolith extracted.

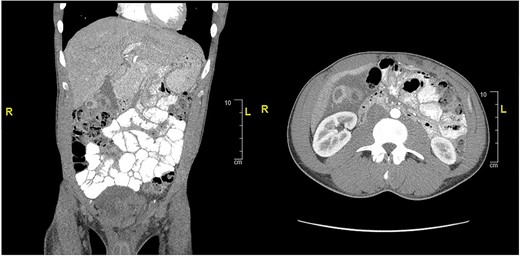

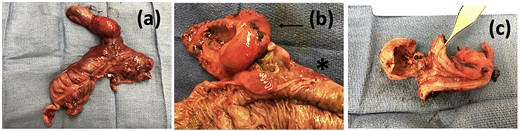

Case presentation #2: A 39-year-old male initially presented with acute cholecystitis (AC) with a markedly thickened wall with abscess formation, not amenable for drainage, treated with antibiotics with improvement, but later experienced recurrent biliary colic symptoms. Repeat computed tomography (CT) imaging (Fig. 4) 2 months later showed a peripherally hyperdense septated collection within the porta hepatis with surrounding fluid signal attenuation; likely representing an abscess seen around the gallbladder possibly secondary to gallbladder perforation due to neoplastic versus inflammatory pathology. Ultrasound showed chronic cholecystitis with cholelithiasis. The patient later underwent elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Intraoperatively, extensive adhesions from the liver to the gallbladder and the colon to the gallbladder were noted. The fundus of the gallbladder was densely adherent to the hepatic flexure with no dissection plane. The hepatic flexure felt firm, raising concern of a possible tumor or fistula. The decision was made to remove the right colon en-bloc with the gallbladder. The gallbladder was dissected free in the usual manner and a critical view was obtained. Once the gallbladder was freed, we proceeded with a laparoscopic right hemicolectomy with ileocolonic anastomosis. The specimen was evaluated on the back table; no tumor was seen, but there was what appeared to be an abscess cavity adherent between the gallbladder and colon filled with green stool-colored liquid. The patient tolerated the procedure well and was progressively advanced to regular diet postoperatively and discharged on postoperative Day 3. His final pathology of the operative specimen (Fig. 5) came back as acute on chronic cholecystitis with a micro-fistula between the gallbladder and the adjacent colon.

CT of abdomen and pelvis showing peripherally hyperdense septated collection within the porta hepatis with surrounding fluid signal attenuation likely representing an abscess seen around the gallbladder.

Operative specimen showing the gallbladder and colon resected in bloc (a) En-bloc specimen (b) Gallbladder (arrow) tightly adherent to colon (start) and (c) macroscopic appearance of the cholecystocolonic fistula.

DISCUSSION

Cholecystitis is a common complication of gallstone disease, which can manifest acutely or chronically. AC is commonly caused by gallbladder inflammation secondary to cystic duct obstruction, accompanied by a triad of right upper quadrant pain, fever and leukocytosis [5]. However, chronic cholecystitis (CC) seen in the second case, is defined as recurrent attacks of AC leading to thickening and fibrosis of the gallbladder [5].

Demographically, CC has a predilection for females in developed countries, with 1–4% of these individuals experiencing symptomatic disease [6]. CC may result in severe complications, including emphysematous cholecystitis, gallstone ileus, gallbladder perforation, cholecystoenteric fistula or, as illustrated here, cholecystocolonic fistula.

Chronic gallbladder inflammation can lead to fistula formation between the gallbladder and the surrounding structures, including the colon, leading to necrosis and ultimately perforation, allowing the gallstones to escape via the fistula, causing impaction downstream in the gastrointestinal tract [3, 7]. CCF may also occur in patients with inflammatory bowel disease and malignancies of the biliary tract, colon or head of the pancreas [8].

Patients with CCF may present acutely with bowel obstruction (usually stones >2.5 cm), bleeding or liver abscess [7]. The patient may initially undergo an enterolithotomy with or without the formation of a colostomy or a resection with anastomosis, depending on the viability of the bowel to resolve the obstruction. Managing the underlying cholecystocolonic fistula has remained a widely questioned topic with no unanimous decision. Options include performing a cholecystectomy during the initial surgical procedure (one-stage), performing the cholecystectomy later once the patient has become more stable (two-stage) or ultimately forgoing the cholecystectomy altogether [4, 7, 9, 10].

In the first case, the severity of inflammation at the level of the infundibulum and fistulous attachment to the colon led us to perform a right hemicolectomy and partial cholecystectomy. In the second case, the patient presented with CC with perforation and surrounding abscess; we decided to perform a cholecystectomy and right hemicolectomy due to extensive adhesions and concern for malignancy or fistula. The most frequently performed procedure is an enterolithotomy, which appears to be performed in critically ill, high-risk patients, followed by cholecystectomy later; or a one-stage procedure (enterolithotomy, cholecystectomy and fistula closure; [1, 10]). In some instances, as seen here, a hemicolectomy can be performed [4]. The literature makes it clear that a debate remains as to which procedure is most appropriate. We argue that the decision to perform each procedure is multifactorial and should be decided on a case-by-case basis. Picking the most appropriate procedure depends on patient presentation, imaging available, patient co-morbidities, surgeon skills and intraoperative findings at the time of surgery. It is clinically relevant to understand the need for and implications of a one versus two-stage operation. Ideally, the best choice would be to address and resolve the fistula and gallbladder pathology. However, the primary goal should always be performing the safest patient-tolerated operation.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

FUNDING

None to report.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

RDSP is the article guarantor. RDSP, GH, KS and KE, collected data, edited pictures, wrote the manuscript. WL and DTF performed the procedures and critical revisions. All authors performed critical review and editing of the manuscript.

PATIENT CONSENT

Informed consent for publication was obtained from the patients. All identifying patient information has been removed to protect patient privacy.