-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Khalid A Alsheikh, Sarah A Aldeghaither, Ali A Alhandi, Total knee replacement in a polio patient with prior extension osteotomy: a case report, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2022, Issue 1, January 2022, rjab575, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjab575

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Poliomyelitis is an infectious disease characterized by a loss of motor neurons. Affected individuals usually suffer from many abnormalities predisposing them to degenerative joint disease. We report a case of a young male, with a history of poliomyelitis, distal femoral extension osteotomy and previous tendon transfer, suffering from severe knee pain. The patient underwent total knee arthroplasty with posterior stabilized Triathlon® for the femoral side reconstruction and Total-stabilizer Triathlon® for the tibia with short stem. At 2-year follow-up, his range-of-motion had improved, and he could walk without pain. This case report emphasizes the value of careful preoperative planning for a complex case with suitable implants and expecting realistic outcomes.

INTRODUCTION

Poliomyelitis is an infectious disease that is characterized by a loss of motor neurons [1]. Affected individuals usually suffer from limb malalignment and shortening with ligamentous laxity, predisposing them to degenerative joint disease [2]. Once osteoarthritis of the knee develops, especially with ligamentous laxity resulting in painful knee, total knee arthroplasty (TKA) is indicated. TKA is challenging in such cases due to abnormal anatomical features such as smaller femoral condyles and bowing of the femur shaft due to possible previous osteotomies. The literature showed that poliomyelitis patients have similar satisfaction rate and functional improvement to others but with higher revision rates [3].

This case reports a different approach to a sever deformity by utilizing constrained short stem knee designs to avoid significant bone cuts and multiple staged surgeries that would have been necessary with long stem knee designs found in hinge total knee replacement surgery.

CASE PRESENTATION

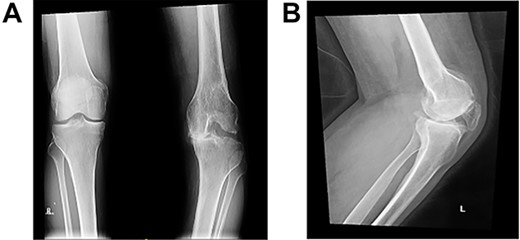

A 48-year-old male was suffering from left knee pain disabling him from doing his daily activities. Twenty-five years prior to presentation, the patient had undergone distal femoral extension osteotomy and tendon transfer as treatment of poliomyelitis orthopedic sequalae. Physical examination revealed left knee genuvarum, medial joint line tenderness and 20–100° for active flexion and 0–110 for passive flexion. Active range of motion (ROM) was only achievable with gravity elimination (Fig. 1). The patient adapted to weakness of his extensors (two-fifths musle powering system of the normal extensor strength) and hip flexors by adopting a gait pattern that involved circumduction of the whole left lower extremity.

Long weight-bearing knee radiographs showed severe osteoarthritic changes, 18° knee genuvarum and extension deformity of the left distal femur (Fig. 2). Skyline view showed severe arthritic changes (Fig. 3).

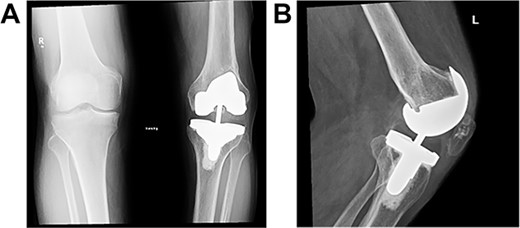

Preoperative plain radiographs; (A) severe osteoarthritic changes affecting the left knee with narrowing of the medial knee joint compartment; (B) left femur with dorsal angulation above the condyles and severe patella baja.

Careful planning and preparation were conducted preoperatively.

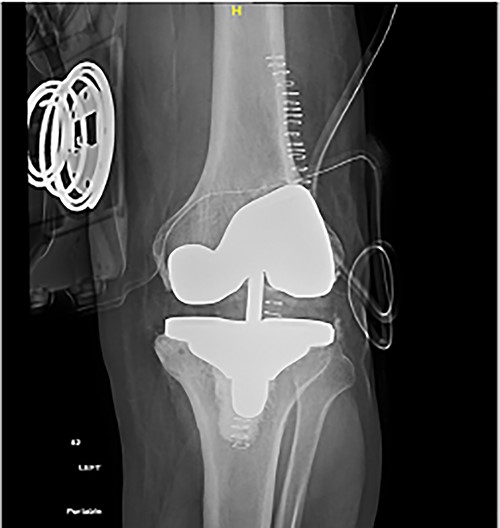

Following templating, the primary posterior stabilized Triathlon® and Total-stabilizer (TS) Triathlon® revision sets were made ready. The TKA was performed through the medial parapatellar approach. Quadriceps’ sparing techniques were avoided to reduce the chance of disrupting the prior tendon transfer. Femoral preparation was carried out first to make sure the distal femur deformity would not impede femoral component positioning. The decision as to whether to go with PS or TS Triathlon femoral components was based on the feasibility of the posterior femoral condyle cuts. The stem was inserted and then the cutting jig was placed. When checking the posterior and anterior cuts, it was noted that no bone would be cut from the posterior condyles using the TS Triathlon cutting block. Hence, the decision to use the primary PS cutting block was made without correcting the distal femoral extension deformity. Following the femoral cuts, tibial preparation was completed using the tibia TS knee system. A short stem of 50 mm was used intentionally due to his reasonably good bone and to allow for longer stems should the necessity arise in the future because of the patient’s young age and the high possibility of revision surgery in polio patients. In addition, this allowed for the use of semi-constrained polyethylene. The patella was found to have small 1-cm2 islands of cartilage, representing the medial and lateral facets. However, the rest of the patella was bare of cartilage. Patellar resurfacing was done to avoid anterior knee pain (Fig. 4).

Weight-bearing and ROM exercises were allowed as tolerated post-operatively.

Upon discharge, the patient was able to flex his knee to 85° and was 4° shy of full extension. Hinged brace was applied, gait re-education and feedback training were carriedout.

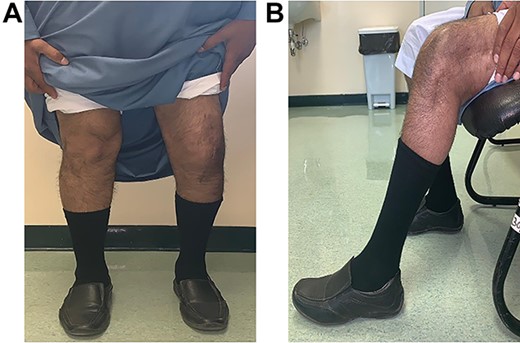

At the 3-month follow-up visit, the patient no longer complained of pain. He walked freely, with a Trendelenburg gait to the left due to an extensor lag (20°) at the operated knee (which was expected due to his preoperative knee extensor muscle power). He was able to fully extend his knee passively when applying anterior pressure (Fig. 5). He also achieved 85° of active flexion (Fig. 6).

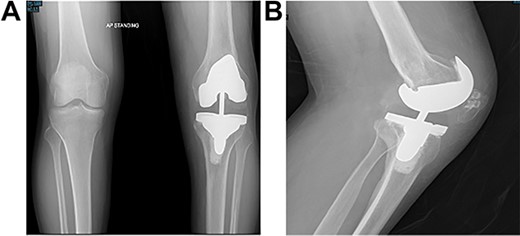

Post-operative plain radiographs from follow-up visits; (A) 3-month post-operative AP radiograph showing implant in place with a lateral gap sized to be 3.2 cm; (B) 3-month post-operative lateral radiograph of the knee showing implant in a satisfactory position.

At the 2-year follow-up visit, the patient’s active ROM continued to be between 4 and 85° (Fig. 7). Patient’s functional outcome score was measured using the Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score pre- and post-operatively, with marked improvement in scores noted from 45 to 76%.

Post-operative plain radiographs at 2-year follow-up visit; (A) 2-year post-operative AP radiograph showing implant in place with decreased lateral gap sized to be 1.57; (B) 2-year post-operative lateral radiograph of the knee showing implant in a satisfactory position.

DISCUSSION

Saudi Arabia has been polio-free since 1995 [4]. However, more and more of the polio sufferers are adults reaching a stage where they need surgical intervention to alleviate pain and instability symptoms. TKA has emerged as a more common treatment for patients with poliomyelitis.

Multitudes of options are available when presented with such complex cases. Previous reports in the literature have demonstrated the utility of different implants with overall acceptable rates of success [1–3, 5–8]. Prasad et al. [1] reviewed a case series totaling 82 knees and showed a 7% total revision rate at a mean of 6 years.

The case presented herein describes the use of an unusual mix of PS and TS implants in the femoral and tibial components, respectively, which has not been reported before. Our aim was to provide a constrained implant. TS implants provide a higher level of constraint, which theoretically provides more stability. However, the compatibility of the two systems provided a unique opportunity to avoid using posterior augments with the TS femoral component and to make a sufficient posterior cut with the PS cutting block due to the anterior angulation of the distal femur. Furthermore, the anterior angulation in the distal femur provided stability to the knee in extension which in turn prompted our decision to veer away from the long-stemmed implants, which would have necessitated a corrective osteotomy to avoid injuring the posterior femoral cortex with an implant stem. The ability of the patient to mobilize with no pain on a stable knee 2-year post-operatively presents promising results for the early outcome of this treatment even when considering the initial widening of the lateral knee compartment in his 3-month visit. The authors hypothesize the widening noted in the lateral compartment was due to the patient’s previous unknown tendon transfers. He possibly underwent a biceps femoris tendon transfer to the anterolateral pole of the patella, which helped him keep his knee locked in extension. However, due to the long history of severe osteoarthritis, his muscles were too weak to stabilize the knee in the post-operative period. This would explain the gradual improvement overtime in the lateral gap seen on radiographs. The literature has little to offer to explain this phenomenon adequately. This case highlights the possible challenges seen in polio-related TKA. Multiple previous surgeries and unconventional biomechanics in this patient population warrant further consideration of the optimum surgical approach to such cases and curb expectations to realistic measures.

CONCLUSION

This case report emphasizes the value of careful preoperative planning for a complex case and expecting realistic outcomes.

FUNDING

None.