-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Ahmad E Al-Mulla, Abdulla E Sultan, Ehab S Imam, Raghad A Al-Huzaim, Swirl sign in post-Roux-en-Y gastric bypass patients: a case series, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2021, Issue 7, July 2021, rjab321, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjab321

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Bariatric surgeries have been increasing with the rising numbers of obese patients. Roux-en-Y is one of the safest and effective bariatric procedures worldwide. Internal hernia is one of laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass complications. Its vague symptoms and late presentation may lead to adverse outcomes. Swirl sign in computed tomography scan has proven to be a particular and sensitive finding to detecting internal hernia in patients with an ambiguous presentation.

INTRODUCTION

Obesity is becoming a pandemic disease [1]. The incidence of obesity is increasing worldwide; 13% of the entire world population are obese, according to the World Health Organization (WHO) statistics published in 2014 [2]. Surgery has proven to be an effective solution to induce weight loss in morbidly obese patients [3]. Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (LRYGB) is one of the most common procedures and it is well documented worldwide. It has excellent results and is low in both morbidity and mortality [3, 4]. Although it is safe, patients may encounter some complications after the procedure. Internal hernia is one of its common complications. Part of the small bowel passes through an iatrogenic defect in the mesentery leading to devastating outcomes, such as bowel obstruction, volvulus, ischaemia, perforation and death. Diagnosis of internal hernia preoperatively can be challenging due to the ambiguous anatomy, vague symptoms and non-specific laboratory results [5]. We are discussing the course and management of two cases from different centres, with internal hernia post-LRYGB.

CASE REPORT 1

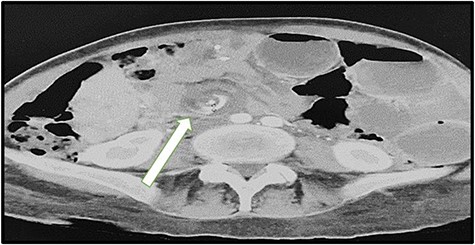

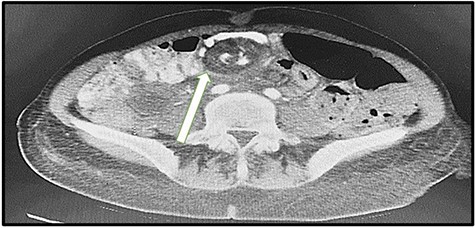

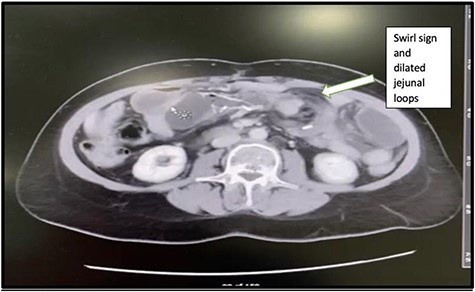

A 43-year-old lady was seen at the Surgical Accident and Emergency Department with a 14-day history of severe colicky abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting. She had a background history of LRYGB in 2011 and laparoscopic repair of internal hernia in 2017. Upon admission, her vitals were pulse (P): 86 bpm, blood pressure (BP): 120/80 mmHg and temperature (T): 37.5. The patient appeared to be malnutrition and dehydrated. Abdominal examination, mild distension, epigastric and para-umbilical tenderness and digital rectal exam (DRE) was empty. Intravenous fluids were administered and laboratory tests were sent. Full blood count (white blood count (WBC): 11.5 109 g/l, HB: 12.0 109 g/l and platelet: 373), kidney profile (creatinine: 37 and urea: 2.1) and lactic acid were high (2.28). We ordered a computed tomography (CT) scan that immediately showed dilated bowel loops with crowded engorged mesenteric vessels showing swirling sign at the paramedian plane, with fluid surrounding the intestinal loops, suggestive of high-grade small bowel obstruction due to internal hernia (Fig. 1). The radiologist compared this result with the CT findings of 2017, which showed the same mesenteric swirling of vessels with a lymph node (Fig. 2). The surgical team discussed the result with the patient, and we obtained consent for exploratory laparotomy.

INTRA-OPERATIVE FINDING

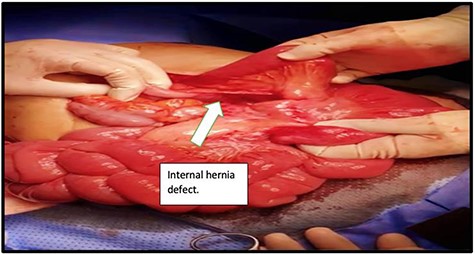

We found trapped dilated and twisted jejunal loops at a defect between the Roux limb and the mesentery of the transverse colon, which is most likely Peterson’s space (Fig. 3). The trapped bowel was untwisted and release. We found no evidence of gangrene nor perforation, only a little amount of clear fluid in the pelvic.

Peterson’s defect found behind the Roux limb and the mesentery of the transverse colon.

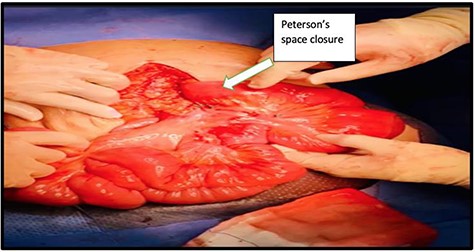

The ample Peterson’s space was continuously sutured with non-absorbable sutures (Fig. 4). The entire small bowel was examined and was checked for appropriate positioning. No other defect was found.

The defect was continuously closed with non-absorbable sutures.

POST-OPERATIVELY

The patient had an uneventful post-operative recovery. She was discharged after resuming a normal diet and regular bowel motion. She was asymptomatic on her 2-week follow-up, and the wound was healing well.

CASE REPORT 2

A 48-year-old-lady presented to our emergency department with 3 days history of colicky abdominal pain. The patient had a background history of LRYGB that was done 2 years ago and a history of laparoscopic internal hernia repair that was done in November 2020. On examination, she was vitally stable (P: 88, BP: 120/86, T: 37.0), with an abdominal examination of mild tenderness at the left upper quadrant region. Her initial laboratory investigations were WBC: 9.6 109g/l, HB: 9.0, PLT: 275, kidney function test (creatinine: 72, urea: 4.5) and lactic acid was normal: 0.8 (range: 0.5–2.2). CT scans of abdomen and pelvis showed mesenteric vessels swirl and dilated small bowel loops with the transitional zone at the jejunal anastomosis (Fig. 5). The patient was improving with intravenous fluids; thus, the initial decision was to conserve. However, 2 days later, symptoms increased. Repeat CBC and lactic showed a marked increase in WBC and lactic acid (12.8 109g/l, 7.8), respectively. Therefore, the patient was shifted to the operating room.

INTRA-OPERATIVE FINDING

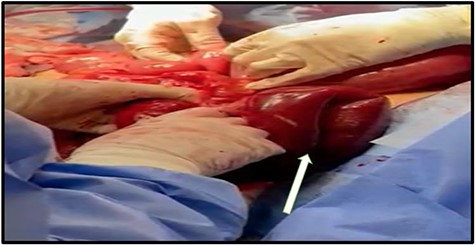

Surgery started laparoscopically; they found the small bowel loops trapped at the Peterson’s space gangrenous (Fig. 6), thus convert to open. The gangrenous part of the jejunum resected. The elementary and biliary-pancreatic limbs were refashioned, and the Peterson’s defect was closed with non-absorbable sutures.

POST-OPERATIVE COURSE

The patient had a drop of haemoglobin and received two pints of blood. A course of broad-spectrum antibiotic was given (tazocin: 4.5 g and metronidazole: 500 mg intravenous) for 4 days. The patient discharged after resuming oral feeding and regular bowel habit. She was asymptomatic in her first 2-week post-operative visit to the surgical outpatient department, with normal appetite, bowel motion and well-healing clean wound.

DISCUSSION

LRYGB is one of the most common procedures performed worldwide, and it provides a desirable weight loss outcome and is considered to be a safe procedure [6–8]. Nevertheless, it might present with some complications, which can be troublesome. Internal hernia is one of the complications that can occur in LRYGB. Located at the iatrogenic spaces created from jejunojejunostomy mesentery or at the space between the anti-colic Roux limb and the mesentery of the transverse colon called (Peterson’s space), this can lead to small bowel obstruction, strangulation and subsequently gangrene and perforation. Internal hernia is more common in LRYGB than in open due to the decrease of adhesion formation and bowel fixation [3]. Incidence of internal hernia post-LRYGB is between 0.2 and 11% of all patients; the mortality rate is around 1.6% [9, 10]. Symptoms of internal hernia are non-specific, and they can be confusing, making the diagnosis challenging. Most of the patients present with vague abdominal symptoms, such as nausea and vomiting. There was no increase in laboratory tests (such as WBC, renal function, liver function or lactic acidosis) unless there is an infarction or perforation occured [5]. A CT scan has proven to be a valuable modality in detecting internal hernia post-LRYGB. Although it is hard to confirm the diagnosis of internal hernia due to distorted anatomy, there are specific findings in CT scan imaging, if present, that raise the level of suspicion.

In 2007 Lockhart et al looked at the specificity and the sensitivity of seven CT scan signs of internal hernia: (i) swirl sign, (ii) strangulation of a superior mesenteric vein, (iii) engorged mesenteric vein and oedema (iv) enlarged lymph node (v) ascites, (vi) mushroom sign and (vii) hurricane eye. They compared the CTs of 18 patients post-LRYGB who were operated for an internal hernia with the control group of 18 patients post-LRYGB with no surgical intervention of internal hernia. After examining all the signs in both groups, they concluded that the swirl sign is the best single indicator of internal hernia with a sensitivity of 61–94% and specificity of 67–89% when compared to the control group [11].

A study in 2009 was looking at the same concept in 10 patients post-LRYGB who had an internal hernia. Their CT scans were reviewed by three radiologists who were looking for signs of internal hernia. They mentioned that mesenteric swirling was the most predictive (sensitivity: 78–100% and specificity: 80–90%). They added that small bowel obstruction and enlarged lymph nodes would raise the percentage of specificity to 100% in predicting internal hernia post-LRYGB [12].

In another study, in 2020, in a high-volume centre assessing 50 patients suspected of internal hernia, the patients were divided into three groups. One of them was a control group. All patients had previous LRYGB and did a CT scan; the study aimed to assess the most specific and sensitive signs on CT scan, and they found that the patient with ‘vessel sign’ (mesenteric swirl, mesenteric vein breaking, mesenteric artery and veins branches inversion) had the highest accuracy when compared to other findings in patients with internal hernia [13].

Both cases mentioned earlier had similar swirl mesenteric sign and the presence of internal hernia intra-operatively. They were proving that it is specific and sensitive to the CT finding.

The surgical approach in internal hernia can be open or laparoscopic depending on the patients’ status and the surgeon’s comfort. It is essential to have a particular technique to repair an internal hernia. Surgeons usually start from a constant point which is the ileocecal valve, and this is important to establish a good understanding and to facilitate the interior hernia repair. Early intervention and closure will benefit the patient and prevent adverse outcomes.

CONCLUSION

Internal hernia presentations can be vague and ambiguous. Patients with mild symptoms can be mistaken for a more serious one. Understanding and prompt interpretation of CT scans can reduce complications and save a life. Swirl sign has proven its specificity and sensitivity in both our cases and in literature. Thus, considering this sign and acting upon it will reduce the rate of complications. However, further studies are warranted to evaluate more patients with similar sign and presentation.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

References

Longitudinal Assessment of Bariatric Surgery (LABS) Consortium, Flum DR, Belle SH, King WC, Wahed AS, Berk P, et al.