-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Giacomo E M Rizzo, Giovanna Rizzo, Giovanni Di Carlo, Giovanni Corbo, Giuseppina Ferro, Carmelo Sciumè, Mirizzi syndrome type V complicated with both cholecystobiliary and cholecystocolic fistula: a case report, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2021, Issue 6, June 2021, rjab239, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjab239

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Mirizzi syndrome (MS) is a common bile duct (CBD) obstruction caused by extrinsic compression from an impacted stone in the cystic duct or infundibulum of the gallbladder. Patients affected by MS may present abdominal pain and jaundice. A 37-year-old male with neurologic residuals post-encephalitis arrived at the emergency department reporting abdominal pain, jaundice and fever. An ultrasound of the abdomen identified cholecystolithiasis with a dilated CBD. He did not undergo CT or MRI due to poor compliance and parents’ disagreement. Eventually, they accepted to perform endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, which diagnosed MS with both cholecystobiliary and cholecystocolonic fistula without gallstone ileum (type Va). Therefore, patient underwent cholecystectomy, wedge resection of the colon and choledochoplasty with ‘Kehr's T-tube’ insertion. A plastic biliary stent was successively placed and removed after 4 month. Ultimately, he did neither complain any other biliary symptoms nor alteration in laboratory tests after 4-years of follow-up.

BACKGROUND

Mirizzi syndrome (MS) was described by Mirizzi in 1948, even if Kehr [1] and Ruge [2] were the first to illustrate it. It is not immediately recognized at radiological evaluation, so it may coexist or even be mistaken for common bile duct (CBD) stones. Moreover, fistula formation may complicate this condition, bringing to a more difficult surgical management. Usually, MS is associated with cholecystobiliary fistula (cholecystohepatic or cholecystocholedochal) [3], as in type II or III according to Csendes et al. Classification [4], but the presence of an internal biliary fistula as cholecystoduodenal, cholecystocolonic or cholecystogastric requires the more recent Beltran Classification [5].

We present a case of a young patient affected by MS due to both cholecystobiliary and cholecystocolonic fistula. We present it in line with the CARE 2017 guidelines [6].

CASE REPORT

A 37-year-old male with neurologic residuals post-encephalitis since the childhood was admitted at our hospital for abdominal pain, jaundice and fever. His parents helped physicians to recognize his complains and to reconstruct his symptoms, since he was not autonomous and compliant. He did not take any medication or herbal supplement, and he had no allergy. They denied an history of previous jaundice or known liver disease. No familiar history of hepatic, biliary or pancreatic diseases were reported.

Initial laboratory results revealed white blood cells (WBCs) 5.90 × 103/ul, hemoglobin 13.0 g/dl, platelets 230 × 103/ul, total bilirubin 6.02 mg/dl (direct 4.48 mg/dl), gamma glutamyl transferase (γGT) 538 (8–61 U/l), alkaline phosphatase 560 U/l (40–129 U/l), aspartate aminotransferase (AST) 139 U/l (3–50 U/l), alanine aminotransferase (ALT) 241 U/l (3–50 U/l), Reactive C protein (CPR) 132 (0–5 mg/l) and normal lipase/amylase. An ultrasound of the abdomen identified cholecystolithiasis with a dilated CBD and normal intrahepatic bile ducts. Alcoholic, autoimmune and viral hepatitis were excluded.

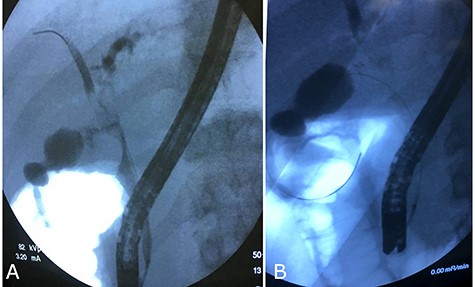

The patient and his parents disagreed to perform firstly a computered tomography scan, and then an magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography. Unusually, they agreed about endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), so it was performed and cholangiography showed an ab-extrinsic stricture of CBD caused by a compression from a biliary stone in the infundibulum of the gallbladder; the upper biliary duct was dilated with various defects as biliary sludge and stones (Fig. 1A). Moreover, late opacification of gallbladder showed lithiasis and, more important, an unexpected opacification of the right colonic lumen (Fig. 1B). MS with both cholecystobiliary (due to the erosion of the wall of the CBD that involves up to two-thirds of its circumference) and cholecystocolonic fistula without gallstone ileum was diagnosed and classified as type III according to Csendes et al. [4] and type V according to Beltran et al. [5]. A partial toilette of CBD was undergone, arranging a drainage with a biliary ‘pigtail’ prob, but the surgical treatment was immediately undergone due to the evidence of fluid faecaloid-like aspiration through the biliary drainage.

Cholangiography first ERCP. (A) Ab extrinsic compression of CBD; (B) tardive opacization of gallbladder showing fistula with colon.

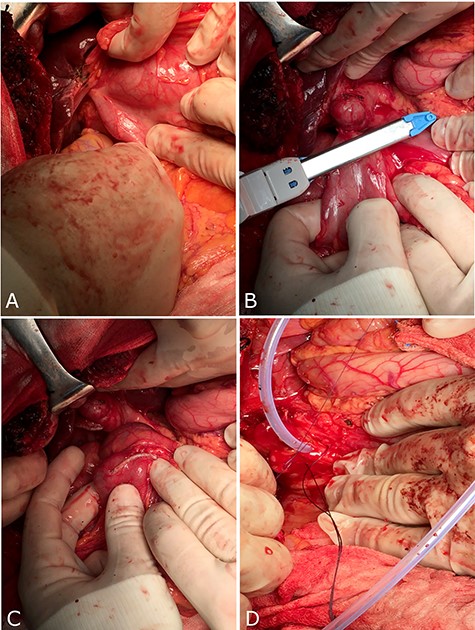

Laparotomy identified an inflamed gallbladder adhering and communicating with the right colon (Fig. 2A). We performed a wedge resection of the fistulizated colon (Fig. 2B and C) and then an incision in the infundibulum of gallbladder for performing intra-surgery cholangiography, which showed residual of stones in CBD. Finally, a complete toilette of CBD and choledochoplasty with ‘Kehr's T-tube’ insertion was performed (Fig. 2D) and cholecystectomy was completed with an intra-abdominal drainage without any complication.

Surgical treatment through a laparotomy. (A) Fistula between gallbladder and colon; (B and C) wedge resection of colon with fistula; (D) insertion of ‘Kehr’s T-tube’ into CBD.

After 24 hours, intra-abdominal drainage was removed, and in the 10th day after surgery, he was discharged with kehr’s T-tube ‘in situ’. Moreover, laboratory results before discharge showed normal blood count and reduction of total bilirubin (1.26 mg/dl), γGT, alkaline phosphatase and transaminases.

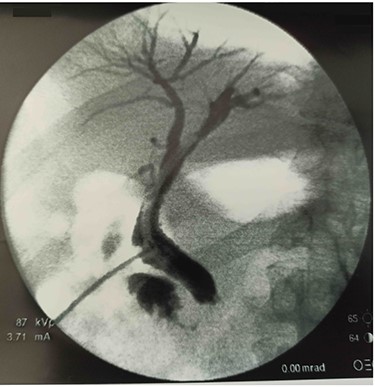

After 40 days, patient had no signs of liver and biliary complications and kehr’s tube appeared normally placed. Blood count and bilirubin was normal with alkaline phosphatase 447 U/l, AST 112 U/l, ALT 162 U/l. Trans-kehr cholangiography showed normal size of CBD (Fig. 3), so it was removed and replaced with a single plastic biliary stent (9-cm length and 10-Fr diameter) through an ERCP.

After fourth month, laboratory tests were normal so ERCP with removal of plastic biliary stent was performed and cholangiography post-removal showed a free and restored biliary tree (Fig. 4).

In the subsequent 4 years of follow-up with his primary care physician, he did not complain any biliary symptom and he constantly showed normal laboratory tests and abdominal ultrasound.

DISCUSSION

MS is a CBD obstruction caused by extrinsic compression from an impacted stone in the cystic duct or infundibulum of the gallbladder [7, 8]. In a single center retrospective study, MS was diagnosed only in 133 patients (2,8%) out of 4800 patients who underwent cholecystectomy [9]. In many patients, MS diagnosis is not achieved before surgery due to the difficulty on making a correct preoperative evaluation, and it is almost impossible to identify it without a second level imaging (CT or MRI). However, our case shows how a timely and well-oriented management of a complicated MS type Va may have a good long-term outcome, although both cholecystobiliary and cholecystocolonic fistula were present. It is uncommon to develop a double fistula, and additionally, it may sometimes be complicated with gallstone ileus. That is why a simplified classification has more recently been proposed, suggesting also the management and treatment of patients affected by MS [10]. According to it, our patient is classified as type IIIa, due to the presence of cholecystocolonic fistula without gallstone ileus. As known, surgical treatment of a cholecystobiliary fistula includes laparoscopic or laparotomic approach, with or without use of ‘kehr’s t-tube’, which we decided to insert not only for protection of biliary tract but also to permit a fast cholangiography later. Nowadays, the laparoscopic approach is broadly diffused in order to reduce time-to-discharge, but effectiveness of both techniques is similar [11], and sometimes, even a rendez-vous with endoscopy may be considered [12]. In our case, we immediately approached our patient with laparotomy, considering the known high risk of conversion in this setting of patient (between 11 and 80% among various studies) [13]. Our management was successful, permitting the patient to be free from biliary disease after a follow-up of 4 years.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

FUNDING

None.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

Dr G.E.M.R.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Resources, Literature search, manuscript writing, design and image providing. Dr G.R.: Manuscript writing, Methodology and Literature search; Dr G.D.C.: Software and image providing; Dr G.F.: Literature search and Image providing. Dr G.C.: Software; Prof. C.S.: Supervision, Comments and data analysis. All the authors (G.E.M.R., G.D.C., G. R., G.F., G.C., G.D.C. and C.S.) revised the manuscript and agreed on its conclusions.

INFORMED CONSENT

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report.

REFERENCES

- magnetic resonance imaging

- ultrasonography

- abdominal pain

- encephalitis

- cholecystectomy

- endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography

- fever

- pathologic fistula

- biliary calculi

- calculi

- common bile duct

- cystic duct

- emergency service, hospital

- follow-up

- jaundice

- laboratory techniques and procedures

- parent

- abdomen

- colon

- gallbladder

- ileum

- wedge resection

- mirizzi's syndrome

- biliary stents

- choledochoplasty

- t-tube

- infundibular stem

- compression