-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Kira Steinkraus, Julian R Andresen, Ashley K Clift, Marc O Liedke, Andrea Frilling, Multifocal neuroendocrine tumour of the small bowel presenting as an incarcerated incisional hernia: a surgical challenge in a high-risk patient, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2021, Issue 6, June 2021, rjab219, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjab219

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Neuroendocrine tumours (NET) of the small bowel present significant clinical challenges, such as their rate of metastasis at initial presentation, common multifocality and understaging even with gold standard imaging. Here, we present a case of a high-risk surgical patient with a complex medical history initially presenting as an acute abdomen due to an incarcerated incisional hernia. He was found at emergency laparotomy to have three small NET deposits in a 30-cm segment of incarcerated ileum which was resected. Postoperative morphological and functional imaging and biochemical markers were unremarkable, but due to clinical suspicion for undetected residual tumour bulk given the non-systematic palpation of the entire small bowel at initial operation, underwent re-operation where a further 70 cm of ileum was found to harbour multiple tumour deposits (n = 25) and was resected. There was no surgical morbidity and the patient remains tumour-free at 9-month follow-up.

INTRODUCTION

Neuroendocrine tumours of the small bowel (SBNET) present significant clinical challenges. With an incidence of up to 1.05/100 000 individuals they are the second most frequent intestinal malignancy [1]. Although the vast majority of SBNET are well-differentiated and of low-to-intermediate grade, metastases to abdominal lymph nodes and/or liver are detectable in 45–90% at initial diagnosis [2, 3]. Here, we present a patient with a metastasised multifocal SBNET found incidentally at the time of emergency repair of an incarcerated incisional hernia.

CASE REPORT

A 57-year-old male patient was admitted to our department with an ‘acute abdomen’ accompanied by nausea and vomiting. On examination, a supra-umbilical incarcerated incisional hernia was evident. His body mass index was 38.3 kg/m2. Blood results included elevated white cell count (12.01 × 103 /ul [4.3–10.0]), CRP (10.69 mg/dl [<0.5]), interleukins (417.2 pg/ml [<15]), creatinine (1.54 mg/dl [0.67–1.17]) and urea (56.6 mg/dl [19–43]). He was taking amiodarone, pantoprazole, bisoprolol, eplerenone, sacubitril/valsartan, eliquis and l-thyroxin.

His complex medical history encompassed dilated cardiomyopathy (ejection fraction 15–20%), atrial fibrillation, left atrial thrombus, implantable cardioverter defibrillator, radioiodine therapy for thyroid autonomy and prior laparoscopic appendectomy for perforated appendicitis with peritonitis.

During emergency laparotomy, a 30-cm incarcerated ischaemic segment of ileum was found. Furthermore, tinny pale intramural lesions were observed to be scattered throughout the ileum. The ischaemic ileal segment was resected and an end-to-end ileo-ileostomy performed. The intraoperative course was impacted by sepsis and cardiopulmonary instability. Postoperatively, he received 4 days of intensive care. There was no surgical morbidity. He was discharged home on postoperative Day 11. Resected ileum histology showed haemorrhagic mucosa and mural necrosis. There were three foci of a well-differentiated NET, measuring 5, 2 and 2 mm, respectively. Immunohistochemistry revealed positivity for CK AE 1/3, synaptophysin, chromogranin and CD56. The lesions were grade 1 (G1) NET (Ki67 < 1%, mitotic activity 1 mitosis/10 HPF). The staging was pT2m, pN0 (0/1) pL0 pV0. Resection margins were confirmed as tumour-free (R0).

Six-week post-surgery, NET-specific workup was initiated. Computed tomography (CT) of the thorax, abdomen and pelvis demonstrated no evidence of neuroendocrine disease. There was no increased DOTA-D-Phe1-Tyr3-Thr8-octreotide (DOTATATE) avidity on Gallium-68 (68Ga) DOTATATE positron emission tomography (PET)/CT. Plasma chromogranin A (CgA) was raised at 104 ng/ml (<102) and 5-hydroxyindole acetic acid (5-HIAA) in 24-h urine was normal at 3.20 mg (2.00–9.00). Retrospectively, the patient denied any symptoms associated with carcinoid syndrome.

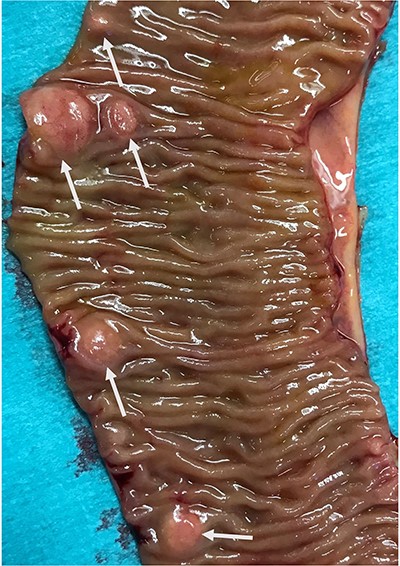

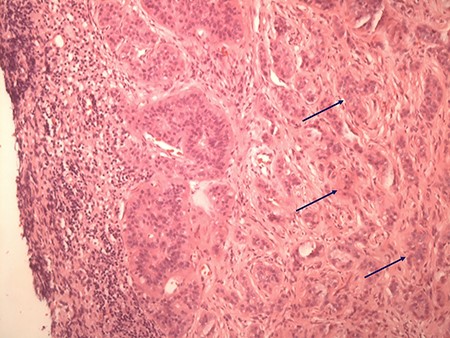

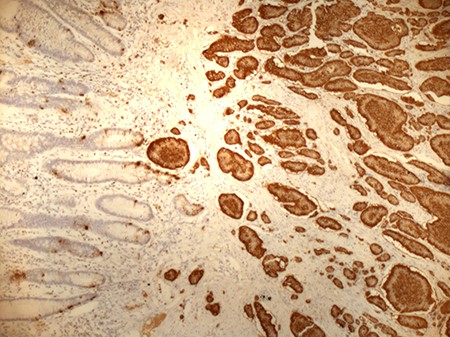

In view of suspected residual neuroendocrine disease not detectable on imaging, he underwent repeat laparotomy. Palpation of the entire small bowel from the Treitz ligament to the ileo-caecal junction was carried out and 70 cm of ileum harbouring multiple intramural deposits resected (Fig. 1). Following an end-to-end ileo-ileostomy, 280 cm of unaffected small intestine remained in situ. The postoperative course was uneventful. Histology demonstrated in total 25 well-differentiated NET (Fig. 2) positive for chromogranin (Fig. 3), synaptophysin and somatostatin receptor subtype (SSTR) 2A. Ki67 was <2% (G1). The tumours were staged as pT1m (largest 18 mm), pN1 (7/41) (largest lymph node 8 mm) and pL0 pV0. All resection margins were tumour-free. At the last follow-up 9 months after completion surgery the patient was alive with no evidence of disease on imaging or biochemistry.

Typical histologic appearance of a well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumour of small bowel (right side, arrows), compared with unaffected ileum (left half of image) on haematoxylin & eosin staining (original magnification ×10).

Positive staining of small bowel NET for chromogranin (original magnification ×10).

DISCUSSION

Our case is of interest for two reasons; it illustrates unique characteristics of SBNET obfuscating diagnosis, and it highlights pitfalls in their surgical treatment. Most patients with SBNET are diagnosed in advanced tumour stages. Bilobar liver metastases with no evidence of the primary tumour on standard imaging are not infrequently observed [4]. Although the sensitivity of somatostatin receptor-based PET/CT technology—the gold standard imaging modality for G1/G2 NET—is as high as 90% [5], tiny intramural lesions or small mesenteric lymph node metastases may escape detection. In our patient, anatomic and functional imaging performed prior to re-laparotomy failed to detect the primary tumours and the locoregional lymph node metastases despite the maximum size of 18 and 8 mm, respectively, and SSTR2-positivity on immunohistochemistry. Video capsule endoscopy and double-balloon enteroscopy have been demonstrated as effective in detecting small bowel pathologies and might be considered in the diagnostic work-up of SBNET obscure to standard imaging [6]. Expression profiling studies have demonstrated genes such as those encoding gastric inhibitory polypeptide receptor (GIPR), bombesin-like-receptor-3 (BRS3) and opioid receptor kappa-1 (OPRK1) have the ability to discriminate between small intestinal and pancreatic primary tumour origin [7].

Neuroendocrine tumour markers generally used in clinical practice failed to reflect tumour burden; CgA was only minimally elevated at 104 ng/ml and 5-HIAA was normal. The value of CgA in this clinical scenario is anyway questionable since the patient was prescribed proton pump inhibitors and had impaired renal function, both known to impact diagnostic accuracy of immunoassays for CgA measurement [8].

All patients with localised SBNET with or without mesenteric lymph node metastases, and those with resectable liver metastases should be considered for surgery with an intent to eliminate macroscopic disease [9]. Meticulous abdominal exploration and palpation of the entire small intestine are pivotal since preoperative imaging understages the disease in up to 70% of cases [3, 10] and in up to 50%, multiple primaries can be found [11]. Resection of primary tumour/s follows the principles of intestinal sparing surgery by avoiding extensive en-bloc resections, preserving the proximal portion of the superior mesenteric artery and vein, and thus minimizing the risk of postoperative short bowel syndrome [12]. Resection of enlarged mesenteric lymph nodes which can be found in typical locations [13] and/or as skip metastases including mesenteric fibrosis [10] is a key component of the procedure and of significant prognostic value [2].

Although few groups report favourable experience with laparoscopic resection of SBNET [14], a minimally invasive approach has to be considered cautiously due to their frequently small size, multicentric growth, and possible encasement of major mesenteric vasculature and retropancreatic space [15].

With a median survival of 56 months the prognosis of patients with metastasised SBNET was dismal in the past [9]. The introduction of somatostatin analogues in diagnosis and treatment and implementation of novel multimodal concepts combining surgery with peptide receptor radionuclide therapy or interventional liver directed treatments have contributed to marked improvement of survival and maintained life quality.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank Dr W. Schumm, Department of Pathology, Westkuestenkliniken, Heide and Professor A. Niendorf, Pathologie Hamburg-West for providing histology images. Written consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

FUNDING

None.