-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Anna M Sauer Durand, Christian A Nebiker, Mark Hartel, Michael Kremer, Bilateral delayed traumatic diaphragmatic injury, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2021, Issue 4, April 2021, rjab052, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjab052

Close - Share Icon Share

ABSTRACT

A 47-year-old patient presented at our emergency department with acute epigastric pain. A thoracic X-ray showed a partially intrathoracic stomach as well as bowel left sided. A following computed tomography scan diagnosed a diaphragmatic hernia. In the patient’s history, 20 years ago a serious car accident was reported as the presumable traumatic origin. Intraoperatively, the diaphragmatic hernia was repaired with a direct suture and mesh augmentation. The rest of the abdomen was clear. In a thoracic X-ray following chest tube removal, herniated small bowel appeared intrathoracally on the right. Relaparotomy showed an extensive diaphragmatic hernia with parts of the liver, small bowel and colon in the right thoracic cavity. Only a partial direct repair was possible, an inlay mesh repair was performed. The further recovery was uneventful.

Bilateral delayed traumatic diaphragmatic hernias are extremely rare, but with a suggestive trauma history thorough intraoperative exploration of the contralateral side should be evaluated.

INTRODUCTION

Traumatic diaphragmatic ruptures occur in 0.8–8% in blunt abdominal trauma [1], thereof 1–6% bilaterally. Two-thirds are not recognized in the initial diagnostic process. They occur especially in polytraumatized patients (Injury Severity Score > 16). A diaphragmatic rupture is an injury severity marker [2] with increased mortality of 30–60% [3], originating mostly from motor vehicle accidents with high kinetic energy [4].

Left-sided ruptures are diagnosed more often (3:1). A hypothetical protective function of the liver is controversial, since right-sided lesions are reported in up to 38% in literature [4]. Diaphragmatic ruptures can be classified as following by the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma (AAST) [5]:

| Grade* . | Description of injury . | AIS-90 . |

|---|---|---|

| I | Contusion | 2 |

| II | Laceration <2 cm | 3 |

| III | Laceration 2–10 cm | 3 |

| IV | Laceration >10 cm with tissue loss <25 cm2 | 3 |

| V | Laceration >10 cm with tissue loss >25 cm2 | 3 |

| Grade* . | Description of injury . | AIS-90 . |

|---|---|---|

| I | Contusion | 2 |

| II | Laceration <2 cm | 3 |

| III | Laceration 2–10 cm | 3 |

| IV | Laceration >10 cm with tissue loss <25 cm2 | 3 |

| V | Laceration >10 cm with tissue loss >25 cm2 | 3 |

*Advance one grade for bilateral injuries up to grade III.

| Grade* . | Description of injury . | AIS-90 . |

|---|---|---|

| I | Contusion | 2 |

| II | Laceration <2 cm | 3 |

| III | Laceration 2–10 cm | 3 |

| IV | Laceration >10 cm with tissue loss <25 cm2 | 3 |

| V | Laceration >10 cm with tissue loss >25 cm2 | 3 |

| Grade* . | Description of injury . | AIS-90 . |

|---|---|---|

| I | Contusion | 2 |

| II | Laceration <2 cm | 3 |

| III | Laceration 2–10 cm | 3 |

| IV | Laceration >10 cm with tissue loss <25 cm2 | 3 |

| V | Laceration >10 cm with tissue loss >25 cm2 | 3 |

*Advance one grade for bilateral injuries up to grade III.

Isolated traumatic diaphragmatic ruptures are rare; a high level of energy is needed. The most common concomitant injuries are as follows [4, 6]:

Pelvic fractures (57%)

Rib fractures

Liver lesions

Cranio-cerebral injury

Fractures

Splenic lesions

DIAGNOSTIC FEATURES

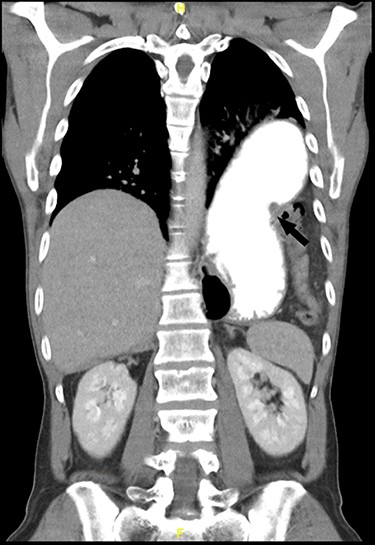

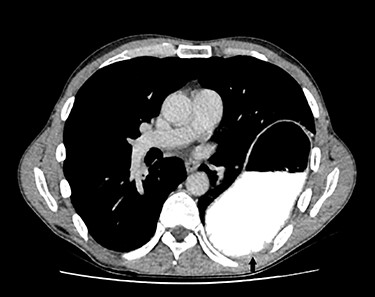

For primary diagnosis, computed tomography (CT) scan is most accurate when suspecting a diaphragmatic lesion [1]. Lesions without herniation are difficult to detect even in thin slices with multiplanar reconstruction. Possible direct signs, besides discontinuity, are the ‘dangling diaphragm sign’, showing a rolled up free diaphragmatic border. Indirect signs are the ‘collar sign’, organs are constricted when passing through the defect (Fig. 1), or the ‘dependent viscera sign’, where abdominal organs touch directly the thoracal wall without interposition of the lung in the supine patient [1, 3] (Fig. 2).

THERAPY

An acute diaphragmatic injury is an absolute operative indication, treated mostly with a direct suture repair with a non-resorbable thread, or in case of a larger defect, a mesh implantation [6].

Delayed diaphragmatic ruptures are reported up to decades after a trauma and usually also require surgery—feasible with transthoracal, transabdominal, open as well as laparoscopic approaches [4, 6, 7].

CASE REPORT

A 47-year-old male patient consulted our emergency department with acute epigastric pain without dyspnea or alteration of bowel function. A thoracic X-ray showed a dilated stomach intrathoracally and colon parts. A CT scan confirmed a left-sided diaphragmatic hernia (69 × 45 mm) with an upside down stomach, herniating small bowel and colon (Figs 1 and 2). The patients’ history includes a severe motor vehicle accident 20 years ago with following coma during 3 months but without abdominal surgery, suggesting a traumatic origin of the hernia.

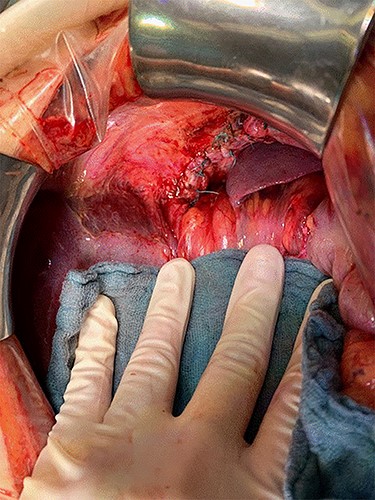

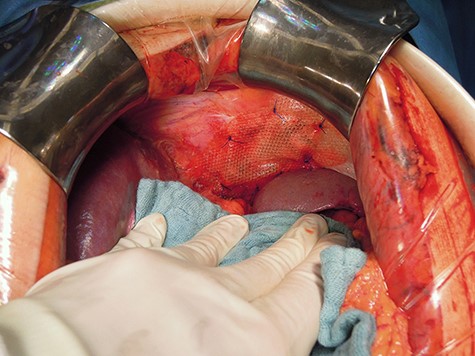

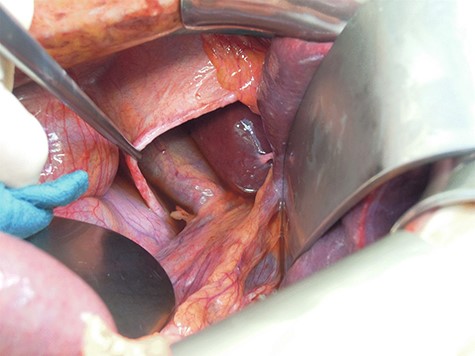

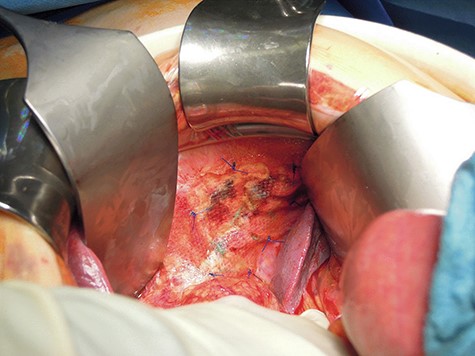

Intraoperatively, the defect could be closed by direct single stitch suture using a non-resorbable, braided thread, reinforced with a Parietene composite® mesh (Figs 3 and 4), a macroporous polypropylene mesh covered with an absorbable synthetic film. Further abdominal inspection was inconspicuous. Tension-free closure of the abdomen was performed. Event-free extubation postoperatively, the standard postoperative X-ray after intraoperative chest tube placement was unremarkable.

After chest tube removal at the third postoperative day, surprisingly, a delayed rupture of the right-sided diaphragm with small bowel intrathoracally was diagnosed on the standard thoracic X-ray in an asymptomatic patient.

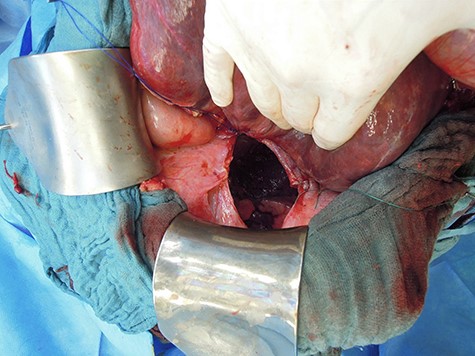

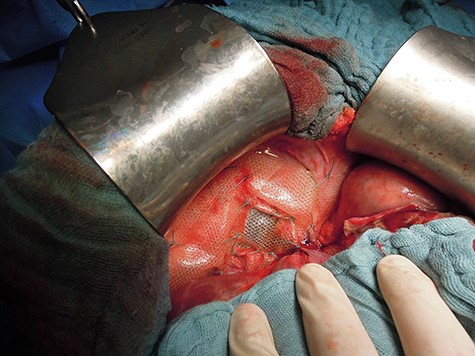

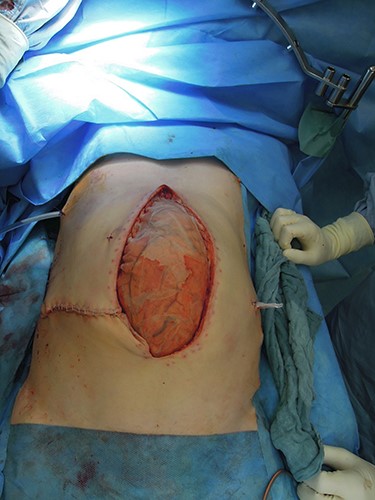

Revision laparotomy was performed, which showed a large diaphragmatic hernia on the right with intrathoracal right liver lobe, small bowel and colon (Fig. 5). The left-sided suture and mesh augmentation remained intact (Fig. 6). Due to the extended defect, only partial tension-free closure was possible, a Parietene composite® mesh was used (Figs 7 and 8) for bridging. Because of high intraabdominal pressure, primary abdominal wall closure was not possible; a gradual closure with an initially bridging vicryl mesh and vacuum therapy was performed (Fig. 9).

DISCUSSION

A very common problem with traumatic diaphragmatic injuries is primary diagnosis. There exist many radiologic indirect signs [1, 3, 9], but even with the technical progress of multidetector CT, a traumatic diaphragmatic lesion is missed in up to over 60% [1, 9] in the initial imaging. The major amount of patients is diagnosed during emergency surgery due to other threatening intraabdominal or thoracical injuries, especially in penetrating trauma because of the defect form caused by white weapons [4, 7, 10]. Up to decades later [7], previously undetected traumatic diaphragmatic hernias are usually diagnosed due to secondary complications like obstruction and/or organ strangulation amongst others [9]. Therefore, preoperative CT scans, mostly thoracoabdominal, are widely available. Furthermore, we think it seems helpful to estimate the extent of surgery needed and guide the patient’s informed consent.

We have to postulate in our patient that from the beginning a bilateral hernia with at least AAST grade IV was present, but because of adhesions between right diaphragm and liver, neither radiologically nor intraoperatively during the first surgery, the hernia of the right diaphragm could be detected. By augmenting the abdominal pressure due to the reposition of bowel on the left side, outgrowing the adhesional forces, the right-sided hernia became apparent.

We used mesh augmentation also on the left-sided hernia, which could be closed by direct suture as recurrence prophylaxis. Valid recurrence rates for suture-only surgery in delayed traumatic diaphragmatic hernia versus mesh augmented are not available due to low case numbers. Since meshes can cause erosion or migrate, benefit–risk assessment should be done by the surgeon evaluating intraoperative tension and tissue quality. Regarding possible recurrence or adverse effects, patient’s surveillance is recommended; here, follow up was 8 weeks postoperatively with further reconsultation upon patient’s request.

CONCLUSION

The risks of collateral damage for complete, bilateral diaphragmatic exposure needs intraoperative consideration and risk assessment, given that bilateral injuries occur only in up to 6% of all traumatic diaphragmatic injuries.

There could be a selection bias depending on the patient collective—blunt versus penetrating trauma—the second caused by white weapons, since right handers are predominant and cause stab wounds on the left bodyside [10]. Relying on literature predominantly described left-sided injuries in guiding surgical exploration may not be an adequate strategy. Intraabdominal adhesions near the diaphragm may indicate an old diaphragmatic hernia that need to be explored.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

FUNDING

None.

REFERENCES

The American Association for the Surgery of Trauma. Injury Scoring Scale Table 6: Diaphragm Injury. https://www.aast.org/resources-detail/injury-scoring-scale#diaphragm (Accessed 22 January 2021).

- diagnostic radiologic examination

- roentgen rays

- computed tomography

- epigastric pain

- traffic accidents

- emergency service, hospital

- diaphragmatic hernia

- hernia, diaphragmatic, traumatic

- intestine, small

- intestines

- intraoperative care

- surgical mesh

- sutures

- wounds and injuries

- abdomen

- colon

- diagnosis

- liver

- stomach

- diaphragmatic injuries

- thoracic cavity

- chest tube removal