-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Cláudia Leite, Pedro Rodrigues, Susana Lima Oliveira, Nuno Nogueira Martins, Francisco Nogueira Martins, Struma ovarii in bilateral ovarian teratoma—case report and literature review, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2021, Issue 3, March 2021, rjab028, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjab028

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Struma ovarii is an uncommon ovarian tumour, defined by the finding of thyroid tissue in the ovary, and more frequently found in teratomas. Symptoms of struma ovarii are nonspecific. The definite diagnosis is made by histological examination. The authors report the case of an asymptomatic 76-year-old female patient, whose ultrasonography, magnetic resonance and computed tomography suggested bilateral ovarian teratoma. Risk of Ovarian Malignancy Assessment score was high. She underwent exploratory laparotomy, peritoneal washing, total hysterectomy, bilateral adnexectomy and intra-operative frozen section. The final pathological report described bilateral mature cystic teratoma with benign struma ovarii. Surgery remains the best treatment.

INTRODUCTION

First described in 1899, struma ovarii is an uncommon ovarian tumour, defined by the finding of thyroid tissue in the ovary, more frequently found in teratomas and occasionally in serous and mucinous cystadenomas. It comprises 1% of all ovarian tumours and 2–5% of ovarian teratomas. Struma ovarii usually presents in the fifth and sixth decades of life and seldom before puberty [1]. Symptoms of struma ovarii are nonspecific: abdominal pain or distension (due to a palpable mass or ascites), abnormal uterine haemorrhage, dyspnoea (due to hydrothorax) and hyperthyroidism. It can be incidentally discovered on imaging or surgery [2]. Differential diagnoses include physiological ovarian cyst, tubo-ovarian abscess, hydrosalpinx, endometrioma, ectopic pregnancy and ovarian tumours. On imaging, struma ovarii usually appear as a multicystic mass with no or moderate wall enhancement and 30% are purely cystic [3]. The definite diagnosis is made by histological examination. Struma ovarii are benign in 90%. However, malignant change occurs in 30%. Papillary thyroid carcinoma comprises 70% of the malignant cases. Metastatic spread occurs in 5% [4].

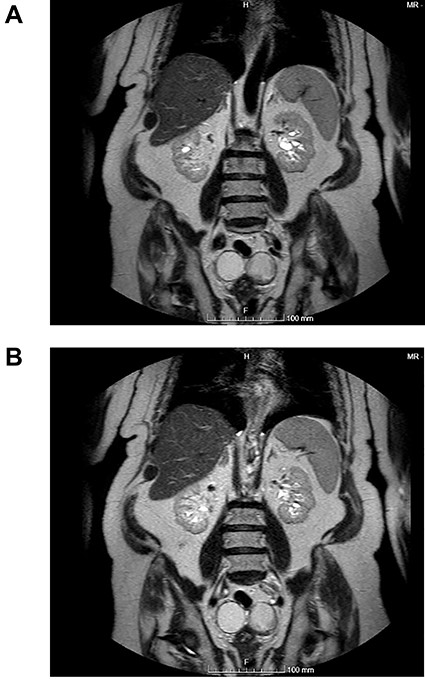

(A and B) Coronal images of MR showing bilateral ovarian teratoma.

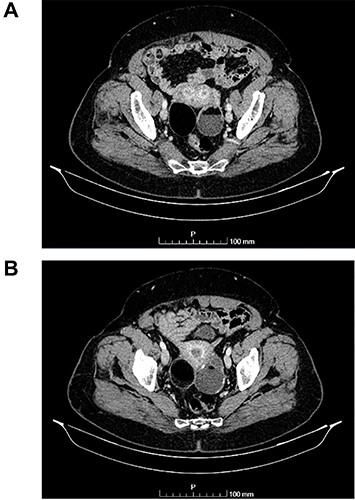

(A and B) Axial images of CT scan showing in the right ovary, a solid mass with predominantly fat density of 55 mm; and in the left ovary, a predominantly cystic mass of 65 mm.

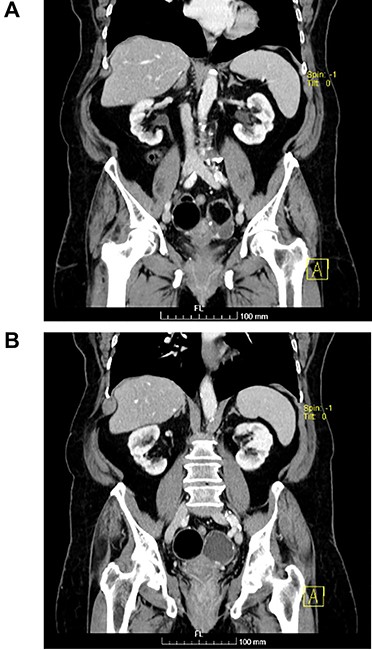

(A and B) Coronal images of CT showing bilateral ovarian lesions.

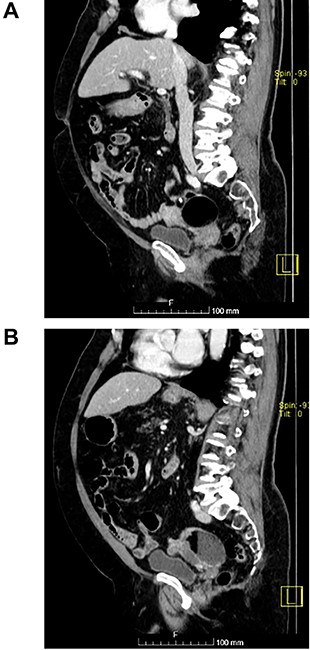

(A and B) Sagittal images of CT showing bilateral ovarian lesions.

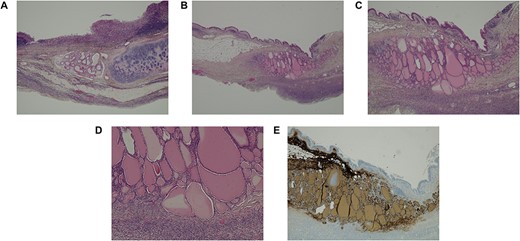

Histological images of the ovaries. (A) Ovary with characteristic features of a mature cystic teratoma (haematoxylin–eosin (HE) staining, 20x). (B-D) Presence of thyroid parenchyma (HE staining, 10x, 40x and 100x, respectively). (E) Positivity for thyroglobulin in immunohistochemistry (40x).

CASE REPORT

The authors report the case of an asymptomatic 76-year-old female patient, referred to our Gynaecologic Clinic, due to suspicious adnexal lesions on a pelvic ultrasound (US). Menopause occurred at age 53. She had no history of abnormal uterine haemorrhage. Her menstrual cycles had been regular. She had had three gestations: two late abortions and one normal delivery, after which she breastfed. At our clinic, upon examination, vulva, vagina and cervix had no apparent lesions. The vaginal US revealed a right adnexal avascular cystic lesion of 65 mm, a left adnexal hyperechogenic cystic lesion of 60 mm, a normal sized uterus, a diffusely heterogeneous myometrium, an endometrial thickness of 8 mm and heterogenous intracavitary liquid. Her risk of ovarian malignancy assessment (ROMA) score was 28.1%, for a cut-off of 25.3%. Cancer antigen (CA) 125 and Human epididymis protein 4 (HE4) were 25.9 and 98.2, respectively. Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), alpha fetoprotein (AFP) and beta human chorionic gonadotropin (bHCG) were normal. She subsequently had a magnetic resonance (MR) done (Fig. 1), which suggested bilateral ovarian teratoma. She also had an upper digestive endoscopy and a hysteroscopy that were normal and a computed tomography (CT) done (Figs 2–4) that showed: in the right adnexal region, a solid well-demarcated tumoural mass of 55 mm, with predominantly fat density, peripherical calcifications and a central hyperdense image (similar to a tooth), suggestive of a teratoma; in the left adnexal region, a predominantly cystic bilobated tumoural mass of 65 mm, with peripherical calcifications and an area of fat density, also suggestive of teratoma; and no additional disease. This case was presented at our Multidisciplinary Tumour Board, where surgery was proposed. Thus, she underwent exploratory laparotomy, peritoneal washing, total hysterectomy and bilateral adnexectomy, which ran uneventfully. Intra-operative frozen section excluded ovarian malignancy. She had an uneventful recovery and was discharged home on the third post-operative day. The pathological report revealed bilateral mature cystic teratoma with representation of the three germinative layers and thyroid parenchymal tissue (struma ovarii) (Fig. 5). Both ovaries were atrophic and had a cavitated lesion covered by respiratory epithelium with hyaline cartilaginous, adipose, smooth muscular and mucosa-associated lymphoid tissues (positivity for CD3 and CD20), seromucinous glands and thyroid follicles (homogenous positivity for thyroglobulin). Thyroid follicles were well differentiated, without features of malignancy. Fallopian tubes were normal. There were also uterine leiomyomas and a mucosal endocervical polyp. She was euthyroid and had a thyroid US done, which was normal. Follow-up at first post-operative month, remaining asymptomatic.

DISCUSSION

Struma ovarii is a rare ovarian tumour, characterized by the presence of thyroid follicles inside the ovary, and more commonly discovered in teratomas, as was the case of our patient [1].

Struma ovarii has no particular symptom and can be an incidental finding. Overall, 20% of patients present with pain and 80% are asymptomatic. Other symptoms include abdominal swelling, abnormal uterine haemorrhage, breathlessness and hyperthyroidism [2]. Our patient was asymptomatic, euthyroid and slightly older than the average age at diagnosis [2]. Differential diagnoses include functional ovarian cyst, adnexal abscess, hydrosalpinx, endometrioma, ectopic pregnancy and ovarian tumours. In our patient, imaging diagnosed bilateral teratoma. The final diagnosis is made by histological analysis. The pathological report of our patient revealed a bilateral mature cystic teratoma with struma ovarii. The ovarian cavities were lined by respiratory epithelium with cartilaginous, adipose, muscular and lymphoid tissues, mucinous glands and thyroid follicles, resembling the anatomy of the neck. Most struma ovarii are benign, as was the case of our patient. Malignant transformation arises in 30%. Predominant sites of metastasis are pelvic structures, peritoneum, omentum, bone, liver and lung [4]. Surgery is the best treatment for benign tumours, and surgery with adjuvant Iodine (I)133 ablation is used to treat certain malignant tumours, as well as metastatic or recurrent tumours [5]. Concerning malignant struma ovarii, when the patient does not desire fertility preservation, surgery comprises peritoneal washing, bilateral adnexectomy, total hysterectomy, lymph node sampling and total thyroidectomy [6]. Instead, following fertility-preserving unilateral adnexectomy, plasma thyroglobulin can be serially monitored as a recurrence marker. Thyroidectomy is recommended before I133 ablation to increase its efficacy. The recurrence rate in patients with malignant struma ovarii who undergo surgery without I133 is almost 50% [7]. Long-term follow-up comprises plasma thyroglobulin monitoring for at least 10 years and whole body scintigraphy with I123 to detect recurrence or metastases. Overall, survival rates are excellent [8]. Thyrotoxicosis occurs in 5% of all cases [9]. Our patient had no associated thyroid disease. Currently, a multidisciplinary approach is mandatory.

Concluding, struma ovarii is an unusual tumour, generally found incidentally on the surgical specimen of a teratoma. Surgery remains the best treatment.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

FUNDING

None.

REFERENCES

- nuclear magnetic resonance

- ultrasonography

- computed tomography

- teratoma

- frozen sections

- dermoid cyst

- ovarian neoplasms

- peritoneal lavage

- struma ovarii

- surgical procedures, operative

- diagnosis

- ovary

- surgery specialty

- thyroid

- ovarian cancer

- hysterectomy, radical

- laparotomy, exploratory

- ovarian germ cell teratoma