-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Lucy Manuel, Laura S Fong, Andrew Mamo, Ramon Varcoe, Wilfred Saw, Peter Grant, Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome following open thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm repair, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2021, Issue 2, February 2021, rjab012, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjab012

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS) is a variant of cardiovascular autonomic disorder characterised by an excessive heart rate on standing and orthostatic intolerance. We present a rare case of a 38-year-old man who underwent open repair of a thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm for a chronic Stanford type B aortic dissection whose recovery was complicated by POTS. He received blood transfusions and was commenced on metoprolol, fludrocortisone and ivabradine with significant improvement in his symptoms. Correct assessment of postoperative tachycardia including postural telemetry is the key to identifying this condition and its successful management.

INTRODUCTION

Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS) is a common, though not well understood, cardiovascular autonomic disorder characterised by an excessive heart rate on standing and orthostatic intolerance. It typically affects younger individuals, 15–45 years, with an 80% female and >90% Caucasian predominance [1, 2]. This case highlights an unusual cause for persistent postoperative sinus tachycardia, with only 2.8% of POTS cases being attributed to surgery [2].

CASE REPORT

A 38-year-old Brazilian man presented with a 4-day history of chest pain radiating to his abdomen and back. He was diagnosed with an extensive Stanford type B aortic dissection originating at the base of left subclavian artery extending into the iliac arteries. With the exception of the left renal artery, visceral branches were supplied by the true lumen. He was managed conservatively with blood pressure control and discharged home. On computed tomography (CT) aortogram 8 weeks later, the dissection appeared stable, however, the diameter of the distal thoracic descending aorta had increased to 64 from 59 mm. His arch was deemed unsuitable for stent grafting due to an acute angle (60-degrees), resulting in a Gothic arch; and he was planned for open surgical repair.

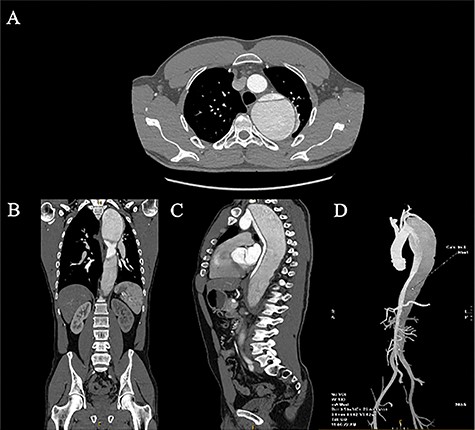

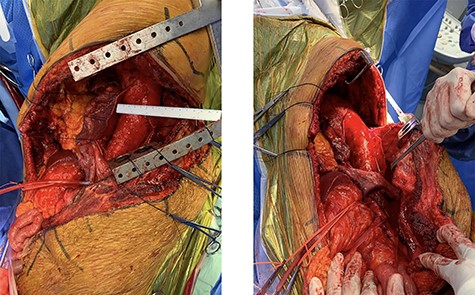

Three months later, the patient represented with severe left sided chest pain. A CT aortogram demonstrated fusiform dilatation of the distal arch and aorta measuring 73 × 69 mm (Fig. 1) with interval false lumen dilation. The decision was made to proceed with an open thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm (TAAA) repair utilising cardiopulmonary bypass with deep hypothermic circulatory arrest. A pre-operative cerebrospinal drain was placed to decrease the risk of spinal ischaemia. The patient was positioned in left lateral position with a thoracoabdominal incision made through the fifth intercostal space. Retroperitoneal dissection revealed vessels of good calibre and an extensive TAAA (Fig. 2). Peripheral cardiopulmonary bypass was instituted via the left femoral artery and vein utilising an 8 mm Dacron graft, and a 25Fr venous cannula. The patient was cooled to 18 degrees Celsius and placed in Trendelenburg positioning for clamping of the mid-thoracic aorta.

April 2020 CT aortogram demonstrating a large 72.7 mm × 68.6 mm fusiform aneurysm: (A) axial slices, (B) coronal slices, (C) sagittal slices, and (D) 3D reconstruction.

The aneurysm was incised and the dissection flap unroofed with a 2 cm cuff created for the proximal anastomosis using a 26 mm Dacron graft. Arterial inflow was established via an 8 mm sidearm, with clamping of the femoral line, deairing of the cerebral circulation and rewarming of the patient. The Dacron graft was then clamped proximal to the arterial inflow and femoral bypass reinstated with the clamp moved to above the diaphragm. Multiple small intercostal arteries were oversewn, with two large intercostals at T10 controlled with Fogarty catheters and anastomosed utilising separate 8 mm Dacron grafts. The cross-clamp was moved to above the renal arteries, allowing a Carrel patch containing the coeliac trunk and superior mesenteric arteries to be fashioned. Continuous perfusion to the superior mesenteric artery was provided via a 12Fr cannula. The femoral inflow was clamped, and the abdominal aortic clamp removed, with fenestration of the aorta to ensure the left femoral artery was supplied by the true lumen. A size 28 mm Dacron graft was anastomosed to the suprarenal aorta, a clamp placed superior to the suture line, and femoral inflow restored. The Carrel patch containing mesenteric vessels was anastomosed to the anterior aspect of the graft.

The graft was positioned through the aortic opening in the diaphragm and the 8 mm Dacron graft supplying the intercostals anastomosed towards the posterolateral. The 26 and 28 mm Dacron grafts were anastomosed in the mid-thoracic aorta with deairing and clamping of femoral inflow. The patient was weaned from bypass without difficulty and the venous line removed with repair of the femoral vein. The femoral and thoracic 8 mm Dacron inflow grafts were ligated and divided, with repair of the diaphragm and costal margins undertaken. The bypass time was 312 minutes and upper body circulatory arrest time 39 minutes. He was transferred to intensive care in a stable condition. His immediate postoperative course was complicated by vasoplegia, requiring noradrenaline, and coagulopathy requiring massive transfusion.

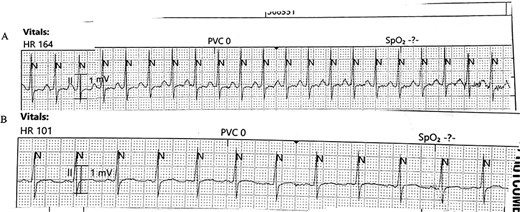

The patient became febrile on day 6 postoperatively and was diagnosed with ventilator-acquired pneumonia and commenced on tazocin and vancomycin. He remained febrile, with surgical wound dehiscence and escalation of his antibiotics to meropenem and vancomycin. Despite adequate treatment of his pneumonia and wound dehiscence with antibiotics and surgical debridement, 3 weeks later the patient had persistent tachycardia to 180 bpm without haemodynamic compromise. Transthoracic echocardiography revealed moderate global impairment with trivial pericardial effusion. Postural telemetry (Fig. 3) demonstrated a sitting heart rate of 101 bpm that increased to 144 bpm on standing and 164 bpm on mobilisation without incrementation of the blood pressure (110/54 mmHg sitting, 100/67 mmHg standing), consistent with POTS. The patient was commenced on metoprolol, fludrocortisone and ivabradine with improvement in tachycardia. He received multiple blood transfusions with increase in haemoglobin from 90 to 110 g/L. He was discharged home 6 weeks after his operation with no disability.

(A) Telemetry demonstrating a heart rate of 164 bpm on mobilization and (B) Telemetry demonstrating a heart rate of 101 bpm on returning to sitting position.

DISCUSSION

The diagnosis of POTS is based on three factors: firstly, clinical syndrome characterised by light-headedness, blurry vision, palpitations, exercise intolerance and fatigue; secondly, an increase of > 30 bpm on standing from recumbent position; and thirdly, the absence of orthostatic hypotension [3–5]. The onset of POTS may be precipitated by immunological stressors including surgery, viral infection, vaccination, trauma, pregnancy or psychological stress [1].

Non-pharmacological treatment remains first-line and involves increasing exercise, lower extremity strengthening, increasing salt and fluid intake, psychological training for anxiety or pain management, and education. Pharmacological therapy is considered on an individual basis, consisting of beta-blockers to blunt orthostatic increases in heart rate, alpha-adrenergic agents to increase peripheral vascular resistance, mineralocorticoids to increase blood volume and serotonin reuptake inhibitors to improve serotonin regulation [4].

There has only been one case report in the literature reporting the development of POTS following thoracic surgery, involving a repair of an aortic coarctation [6]. Similarly, identified potential risk factors included surgery, prolonged bed rest, and use of antihypertensives that worsen orthostatic intolerance. Additional risk factors in our case include reduced oral intake, anaemia, autonomic insufficiency and insomnia [1]. Correct assessment of postoperative tachycardia including postural telemetry is the key to identifying this condition and its successful management.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

FUNDING

None.

References

- metoprolol

- tachycardia

- heart rate

- distal aortic dissection

- autonomic nervous system diseases

- blood transfusion

- cardiovascular system

- fludrocortisone

- telemetry

- postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome

- thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm

- ivabradine

- cardiothoracic surgery

- orthostatic intolerance

- repair of thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm