-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Darwin S Espin, Jorge F Tufiño, Jaime M Cevallos, Fernando Zumárraga, Vanessa E Orozco, Estefany J Proaño, Gabriel A Molina, A needle in the colon, the risk of ingested foreign objects: a case report, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2021, Issue 11, November 2021, rjab455, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjab455

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Ingestion of foreign bodies is often found in clinical practice; however, intestinal perforation due to ingestion of foreign bodies is rare. Sharp and metallic objects are usually the ones that cause most complications. Preoperative diagnosis is difficult since the clinical presentation is vague and nonspecific presentation can simulate many abdominal pathologies. Patients are rarely aware of foreign body ingestion, and a high index of suspicion is required to make a timely diagnosis. In addition, treatment demands prompt surgery to avoid dangerous complications.

We present the case of a 19-year-old tailor; he inadvertently swallowed a needle and presented to the emergency department with a colonic perforation. Surgery was required, and he recovered completely.

INTRODUCTION

Accidental ingestion of a foreign object is a frequent problem at the emergency department [1]. Although most ingested foreign objects pass through the gastrointestinal tract without any harmful outcomes, in up to 1% of the cases, perforation can occur at some point in the gastrointestinal tract [1, 2]. Sharp objects, chicken bones and fish bones account for half of the reported perforations [2]. Since clinical symptoms are nonspecific preoperative diagnosis of intestinal perforation secondary to foreign body ingestion requires a high degree of clinical suspicion and awareness [1, 3].

We present the case of a healthy young man; after swallowing a needle, he presented to the emergency department with a colonic perforation. Surgery was required, and he recovered completely.

CASE REPORT

The patient is an otherwise healthy 29-year-old tailor without any past medical history. He presented to the emergency room with a 4-day history of lower abdominal pain. At first, the pain was mild and located in the upper abdomen and lower left-back. However, as the days passed, the pain migrated to his lower left abdomen, became sharp, and was accompanied by cramping, fever, severe nausea and vomits. Thus, he presented to the emergency room. On clinical examination, a tachycardic patient with tenderness in his upper left abdomen and lower back was encountered. With these symptoms, urolithiasis was among the differential; therefore, a complete blood count along with an abdominal computed tomography (CT) was requested.

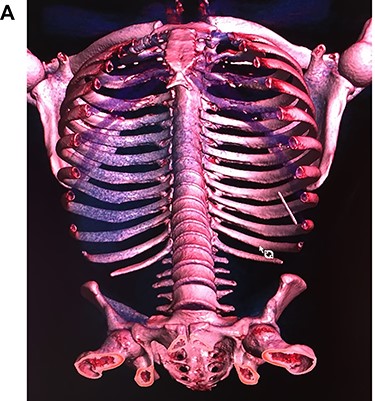

Leukocytosis with neutrophilia was detected, along with an elevated C-reactive protein. On the CT, a high-density object was seen in the descending colon; the object resembled a 4.5 cm needle that perforated the whole extent of the colonic wall. Surrounding this area there was inflammation with mesenteric edema. No lymph nodes or other masses were detected (Fig. 1A, 1B, 1C).

With these findings, surgical consultation was required, and surgery was decided on a laparoscopic approach.

On laparoscopy, multiple adhesions between the omentum and descending colon were seen and released using an ultrasonic energy device (Harmonic, Ethicon US, LLC., Cincinnati, OH, USA). After mobilization of the left colon, the needle was seen stabbing the colonic wall 7 cm away from the splenic flexure. The needle was removed, and the perforation was sutured using a 2-0 absorbable suture without any complications. No other perforations were seen, and the procedure was completed without any complications (Fig. 2A, 2B).

The patient’s postoperative course was uneventful; he completed a short course of broad-spectrum antibiotics and was discharged on the fifth day without any difficulties. During follow-up controls, he finally remembered swallowing the needle. He recalled having a coughing episode while he was holding multiple needles in his mouth. After surgery, he changed his working habits, and the patient is doing well without any complications.

DISCUSSION

Incidental ingestion of bodies is a frequent phenomenon in the general population [1]. Most of them transit through the intestine and pass with the stools without any clinical or surgical intervention [1, 2]. These occasional events arise mainly as accidents among children or adults with psychiatric conditions (depression, suicidal, manipulative); nevertheless, anyone can be affected [3]. The majority of cases reported before 1900 happened to women who had the practice of holding needles and pins between their lips while sewing [1, 2]. The same happened to our patient.

Once the object is embedded intraluminally, it depends on its morphological characteristics to whether it perforates immediately or progresses to an obstruction [4]. For example, large or round objects such as coins usually get caught in the gastroesophageal junction [1, 4]. On the other hand, when sharp objects are ingested, they can be trapped in areas of anatomical narrowings such as the ileocecal valve, appendix or regions with acute angulations such as intestinal adhesions, tumors or hernias [3, 5].

Thankfully, the intestine has an intrinsic ability to protect itself from perforations; when the bowel wall is affected and punctured, the mucosa enlarges the bowel wall at the point of contact, allowing easier pass of that object [6]. Yet if the object is metallic, sharp, stiff or pointed, it is more likely to cause complications such as an abscess, adhesions or fistulas [2, 7]. In addition, when a foreign body perforates the bowel wall, it can follow several routes; it can lie trapped to the bowel wall, lie close to the perforation site, or migrate distally and perforate it again [4, 7]. In our case, the needle was found piercing the colonic wall but was not free in the abdominal cavity.

Symptoms of perforation by foreign objects are vague and can mimic other causes of abdominal pain, including appendicitis, inflammatory masses and ureteric colic [1], as in the case of our patient.

In addition, diagnosis is usually complex since most patients do not recall swallowing any object [2, 8]. Another factor that may influence therapeutic strategies is the radiological characteristics of the ingested object [4, 5]. For example, if it is radiopaque, it allows easier identification [2, 4]. However, if toothpicks or other wood material are swallowed, it may delay the diagnosis and lead to more severe complications [9]. Treatment is usually straightforward; if an ingested foreign body is detected, the first approach should be endoscopic to remove it [1, 2, 3]. However, if it fails, and there is a high risk of perforation, surgery should not be delayed [3, 4]. Conservative approaches have been attempted, but treatment should be aggressive in most cases [6]. Laparoscopic or open procedures have low mortality and morbidity rates, which may prevent these patients from developing severe complications [9]. In our case, surgery was decided after the needle was detected and extracted without complications.

Prevention of ingestion is the best treatment, as the potential dangers of accidentally ingested foreign objects may lead to severe complications. Due to its broad spectrum of symptoms, a high index of clinical suspicion and timely surgical consultation is needed to reach a correct diagnosis and prompt treatment.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

FUNDING

None.