-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Oliver J Harrison, Mark Jackson, Emily Shaw, Aiman Alzetani, Tracheal leiomyoma mimicking asthma for over 20 years, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2020, Issue 9, September 2020, rjaa323, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaa323

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

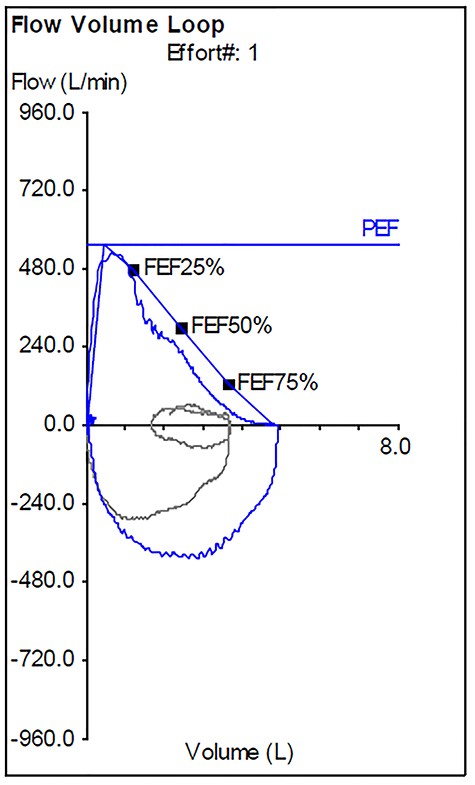

Benign tracheal tumours have an incidence of 1 in 1,000,000, of which leiomyomas represent only 1%. We report a case of tracheal leiomyoma masquerading as asthma for over 20 years. A 48-year-old man presented aged 26 years with asthma symptoms unresponsive to treatments and an obstructive spirometry pattern. Symptoms were not particularly troubling but suddenly exacerbated 22 years later. Flow-volume studies were consistent with upper airway obstruction. Computed tomography chest revealed a 2.3 cm mass arising from the posterior aspect of the trachea 2 cm above the carina. Bronchoscopic resection was performed using a Nd:YAG laser. Histology confirmed leiomyoma. Follow-up after 6 weeks revealed complete resolution of symptoms with normal spirometry. Tracheal masses should be considered in any patient with atypical asthma. A flow-volume loop may provide a clue to diagnosis and bronchoscopic laser resection is a minimally invasive treatment option.

INTRODUCTION

Benign tracheal tumours are extremely rare with an incidence of 1 in 1,000,000, of which leiomyomas represent only 1% [1]. Since the first report in 1952, there have been less than 30 additional cases [2]. Most present after a lengthy period (3–7 years) of worsening respiratory symptoms commonly mistaken for asthma or chronic bronchitis [3]. They are histologically benign and slow-growing, arising from the posterior membranous portion of the trachea. We report a case of tracheal leiomyoma presenting over 20 years prior to the correct diagnosis. We advocate the flow-volume loop as a simple test to diagnose upper airway obstruction and recommend bronchoscopic laser resection as a minimally invasive alternative to major tracheal resection.

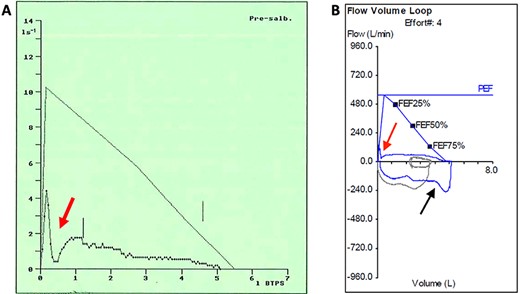

Pre-operative flow-volume loops: (A) expiratory flow-volume trace from initial presentation aged 26 years demonstrates pressure-dependent collapse on expiration (red arrow); (B) complete flow-volume loop obtained aged 48 years demonstrates a similar appearance with clipping of the inspiratory loop (black arrow) due to variable intrathoracic obstruction by the tracheal leiomyoma.

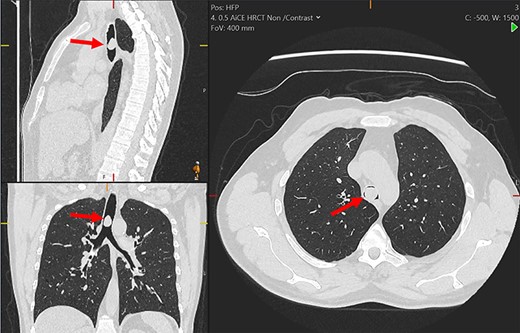

Multiplanar reformation of the chest computerized tomography demonstrating the tracheal mass (red arrows).

CASE REPORT

A 48-year-old man presented with worsening breathlessness and a feeling of being unable to breathe deeply. He was an ex-smoker (10-pack-year) and had occupational exposure to dust, welding and paint fumes working in a dockyard. Aged 26 years, he was found to have an erratic pattern of airway obstruction uncharacteristic of classical asthma. Exacerbations had no trigger and there was minimal improvement of peak expiratory flow (PEF) rate with inhaled bronchodilators. Initial spirometry then revealed forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) = 1.85 l (predicted 4.40 l) and forced vital capacity (FVC) = 3.60 l (predicted 5.10 l) increasing to 2.20 l and 5.00 l, respectively, following salbutamol administration. An exhaled nitric oxide test was not elevated; however, skin testing was positive to house dust mite, grass, trees, cats and dogs. The patient was maintained on a combination of inhaled salbutamol, fluticasone/salmeterol and oral montelukast with oral prednisolone and antibiotics for exacerbations. There was no symptom improvement with any treatment combination over 22 years.

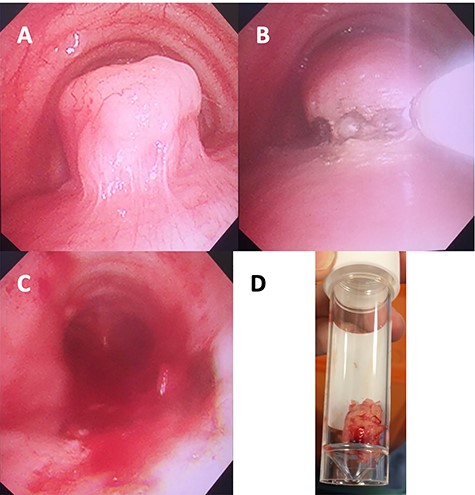

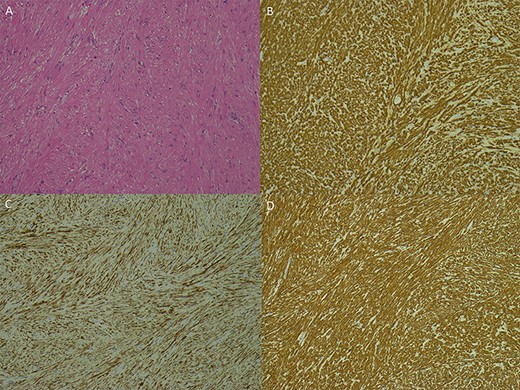

On examination, he had normal chest expansion and no hyperinflation. Expiration was not prolonged and there was no expiratory wheeze or inspiratory stridor. Repeat spirometry revealed FEV1 = 0.98 l (predicted 3.90 l) and FVC = 5.10 l (predicted 4.84 l) with an expiratory flow-volume loop demonstrating pressure-dependent collapse and a clipped inspiratory loop, which suggested upper airway obstruction (Fig. 1A and B). The patient was referred for a computed tomography chest which revealed a 2.3 cm × 1.5 cm polypoid mass arising from the posterior aspect of the trachea approximately 2 cm above the carina (Fig. 2). Bronchoscopy was performed and the mass resected using Nd:YAG laser (Fig. 3A–D). The lesion was wide-based arising from the trachealis muscle mucosa. The patient was discharged the same day. Histological analysis revealed a spindle cell lesion with a fascicular arrangement suggesting smooth muscle differentiation without malignant features (Fig. 4A–D). Immunohistochemistry confirmed the expression of smooth muscle actin, desmin and H-caldesmon, in keeping with leiomyoma. Follow-up at 6 weeks revealed complete resolution of symptoms. Repeat spirometry demonstrated FEV1 = 3.56 and FVC = 4.94 and the flow-volume loop had normalized (Fig. 5).

Images of the mass obtained intraoperatively: (A) bronchoscopic view of tracheal leiomyoma; (B) laser resection; (C) post-resection view; (D) resected tumour in a specimen tube.

Photomicrographs of the specimen: (A) spindle cell lesion, haematoxylin and eosin; (B–D) immunohistochemistry with H-cadesmon (B); desmin (C), smooth muscle actin (D); all at ×100 magnification.

Post-operative flow-volume loop demonstrating a normal appearance.

COMMENT

A diagnosis of tracheal mass should be considered where presentation and response to treatment for asthma are atypical. Over-diagnosis of asthma is well recognized and symptoms in the present case did not align well with classical asthma [4]. The lack of response to asthma treatments could have prompted the clinical review, as could a normal exhaled nitric oxide level, which has a negative predictive value around 90% [5].

Similarly, the importance of the flow-volume loop as a simple method for detecting upper airway obstruction has not been stressed in previous reports. The pre-operative loop demonstrated markedly reduced PEF followed by a further rapid reduction, most likely due to the posterior tracheal wall bulging forward during the forced manoeuvre allowing the tumour to almost completely obstruct the tracheal lumen (Fig. 1A and B). The inspiratory loop was not classical for intrathoracic obstruction appearing clipped because of the magnitude of the obstruction and variable as the tumour oscillated on its wide stalk. We strongly advocate performing a flow-volume loop in the setting of atypical asthma to help exclude a tracheal mass.

Various treatment strategies have been employed for resecting tracheal leiomyomas including bronchoscopic debulking, wire snare, laser and open tracheal resection [6]. Reports of recurrence necessitate complete resection at the index operation [7]. Open surgical resection is advocated for tumours with a wide base where complete bronchoscopic resection may be challenging. However, this approach is associated with morbidity and increased length-of-stay [6, 8]. We opted for a minimally invasive approach and achieved a good resection using laser despite a wide-based lesion. Furthermore, thermal extension from the laser margin may help reduce the risk of recurrence. Follow-up with repeat bronchoscopy will be essential.

In summary, tracheal masses should be considered in any patient with treatment-resistant or atypical asthma. We advocate bronchoscopic laser resection as a minimally invasive approach, which may promote adequate resection margin. Long-term recurrence is unknown and the rarity of these lesions suggests the optimal treatment strategy may take many more years to elucidate.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

FUNDING

None.