-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

F Xavier Moyón C, Gabriel A Molina, Christian L Rojas, Miguel A Moyón C, Jorge F Tufiño, Andrés Cárdenas, Oscar L Mafla, John E Camino, Ligia Elena Basantes, Marcelo Stalin Villacis, Obesity and ventral hernia in the context of drug addiction and mental instability: a complex scenario successfully treated with preoperative progressive pneumoperitoneum, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2020, Issue 8, August 2020, rjaa261, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaa261

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Surgery in loss of domain hernia can result in high morbidity and mortality. Chronic muscle retraction along with the reduced volume of the peritoneal cavity can lead to potential problems such as abdominal compartment syndrome, ventilatory restriction and an elevated risk of hernia recurrence. This is affected even further by obesity; a high body mass index is strongly associated with poor outcomes after ventral hernia repair. In these individuals, preoperative preparation is vital as it can reduce surgical risks and improve patients’ outcomes. There are many strategies available. Nonetheless, an individualized case approach by a multidisciplinary team is crucial to accurately treat this troublesome pathology. We present the case of a 41-year-old obese patient with a loss of domain ventral hernia. As he had a drug addiction and several psychologic difficulties, a tailored approach was needed to successfully treat the hernia. After preoperative preparation and surgery, the patient underwent full recovery.

INTRODUCTION

Abdominal wall repair is one of the commonest surgical procedures worldwide [1, 2]. Thanks to tension-free techniques and improved knowledge of hernia formation and management, more patients are now able to achieve complete recovery [1, 3]. Obese individuals are a special group of patients in which hernias represent a complex challenge, since its management, risk of complications and recurrence is high [3, 4]. There are many treatment modalities; however, they must be assessed by a multidisciplinary team in an individualized case approach to accurately approach the patient [2, 5]. We present the case of a 41-year-old obese patient with a ventral hernia. Due to his comorbidities, bariatric surgery was not an option. After nutritional, psychiatric and surgical assessments, the hernia was successfully treated and the patient underwent full recovery.

CASE REPORT

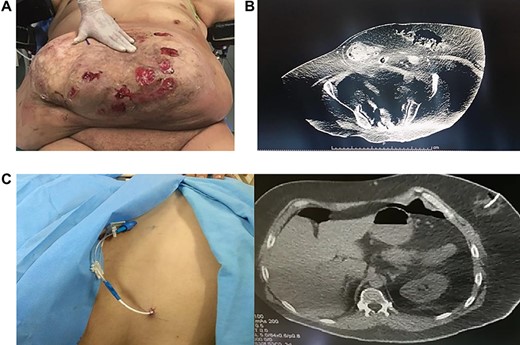

Patient is a 41-year-old man with past medical history of hypertension, Grade II obesity (body mass index 41 kg/m2) and a history of recurrent drug abuse (marijuana, alcohol and cocaine). He presented to our office with a 15-year history of a ventral hernia. At first, the hernia was small and did not cause any symptoms; however, as time passed, the hernia grew larger, and due to it, the patient experienced trouble eating, resting and had difficulties in almost every physical activity. This combined with his weight gain completely changed his relationships and altered his mental stability, further worsening his drug addiction. On clinical examination, a huge 15 × 20 cm ventral defect on the midline was identified. The skin around the defect was covered with multiple ulcers and had a fetid discharge (Fig. 1A). On palpation over his ventral hernia, no pain or signs of incarceration were discovered. His laboratory values were normal, and a contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) revealed the abdominal wall defect in the midline (Fig. 1B). The hernia sac was filled with loops of the edematous bowel and the abdominal wall muscles were atrophied and fibrotic; the relationship between the volume of his hernial sac and the volume of the abdominal cavity was 28%. A ventral hernia with loss of domain was diagnosed and a multidisciplinary approach was decided. Psychiatric, nutritional and surgical consultations were required to treat the emotional and physical ramifications of the hernia. Bariatric surgery was considered as an option prior to hernia treatment; however, due to his drug addiction, it was not a viable option. Preoperative progressive pneumoperitoneum (PPP) was decided. After treatment of the skin ulcers, PPP was achieved using a 7-Fr catheter. The catheter was placed under CT guidance in the upper left quadrant in the midaxillary line (Fig. 1C). The initial insufflation volume was 1000 cc of ambient air while we closely monitored signs of pain, nausea or vomiting. Since the patient remained asymptomatic, he was discharged and was kept on close follow-up as an outpatient. We insufflated 500–700 cc of ambient air daily for 2 weeks until surgery; the procedure lasted 45 minutes, and during this time he received a daily enoxaparin injection and psychiatric therapy. We halted insufflation as his abdominal circumference was stationary for 2 days.

(A): Abdominal hernia, ulcers are seen on the skin. (B): Abdominal CT, multiple loops of bowel in the hernia. (C): Catheter is placed of insufflation.

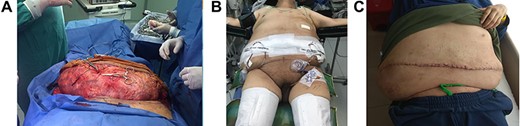

The patient underwent an anterior component separation procedure. After dissection of the hernia sac (Fig. 2A), the external oblique aponeurosis was identified and divided 1 cm away from the rectus sheath. The rectus muscles were approximated in the midline, and a 30 × 30 polypropylene mesh was placed onlay and anchored with absorbable sutures in the costal margin. Two Jackson Pratt drains were placed, and the excess skin and subcutaneous tissue were removed (Fig. 2B). His postoperative period was uneventful; diet was initiated on the second postoperative day without complications and was discharged on his seventh postoperative day. On follow-up controls, the drains were removed due to low and serous output (Fig. 2C). Six months after the initial procedure, the patient is doing well without surgical complications and on psychiatric follow-up.

(A): Hernia sac. (B): Patient after surgery. (C): One month after surgery, patient doing well.

DISCUSSION

Management of large ventral hernias (>10 cm) in obese patients represents a challenging scenario for the medical team, since repair carries a high risk for postoperative complications [1, 2] (morbidity rate of 32%, mortality of 5% and a recurrence rate of 53%). This pathology has seen a rise in its frequency due to the obesity epidemic and the increasing number of abdominal operations [2, 3] (1–11% of laparotomy wounds develop incisional hernias and 20–30% will have recurrence) [1, 2]. When the volume of the hernia can no longer be reduced into the abdominal cavity and no space is left in the abdomen to accommodate the viscera, the hernia is called a loss of domain hernia [1–3]. As it happened to our patient, this event, which was first described by Rives et al. in 1973, causes a series of processes that change the anatomy of the abdominal wall [1, 5]. Once the linea alba is divided, the muscles retract laterally and the hernia will gradually enlarge; if left untreated, the abdominal muscles will atrophy and become fibrotic [2]. As the intra-abdominal pressure reduces, the diaphragm will descent and alter respiratory functions [4, 6]. Portal stasis will result in mesenteric and bowel edema that in turn will affect the surgical reduction of the hernia sac [4, 6]. Preoperative diagnosis is critical and CT plays a key role in diagnosis and prognosis [2]. If the relationship between the volume of the hernial sac and the volume of the abdominal cavity in the CT is >25%, it indicates a loss of domain and predicts which patients will require preoperative preparation [4–6]. If surgery is performed without preoperative assessment, troublesome complications such as renal failure and intestinal ischemia can appear [1, 2]. Therefore, several strategies are available that include: PPP, tissue expansion devices, inlay meshes, component separation, bowel resection, bariatric surgery and botulinum toxin Type A [1, 2, 7]. Bariatric surgery in a two-stage setting can be helpful as it can improve conditions for further repair; nonetheless, when making decisions regarding the candidacy of a potential patient, providers should always weigh the risks against the benefits of weight loss surgery [3, 8]. In our case, since our patient had a history of drug abuse, and since active drug or alcohol abuse is a relative contraindication to surgery [11], it was not considered a viable option.

In 1947 Moreno et al. described a method to gradually expand the capacity of the abdominal cavity and facilitate the closure of the hernia defect reducing the ventilatory risks [1, 9]. PPP is a technique in which ambient air, CO2 or O2 is insufflated through a catheter into the abdomen [4, 10]. This allows gradual adaptation to the increasing intra-abdominal pressure and simulates the reintroduction of the viscera; this, in turn, decreases adhesions, reduces mesenteric edema and the diaphragm adapts to its new respiratory dynamics [1, 2, 4].

The intra-abdominal pressure and infused volume must be measured in each session to prevent complications and to oversee treatment since PPP must be stopped when the abdominal circumference is stationary for 2 days, as it provides no more benefits [2, 11]. In rare cases, patients may need up to 24 sessions to be ready for surgery; nonetheless, current literature suggests that PPP should be used for no more than 15 days [1, 2]. Patients should be considered ready for surgery when the hernia sac is reduced, and the abdominal wall can withstand the surgery confirmed by the measure of the abdominal circumference in tomography [4]. In our case, the patient had 15 days of insufflation without complications.

Complications associated with this technique include subcutaneous emphysema, abdominal wall infection and respiratory distress [2, 3]. With this technique, abdominal volume increases by 53%, and the reduction of the hernia can be achieved in 94% of the cases [2, 7].

As it was achieved with our patient, preoperative diagnosis and close follow-up are essential in these high-risk patients as the chance of recurrence (0–32%, most commonly <10%) and complications is high [6].

A multidisciplinary team is needed to adequately treat these patients. Psychologists, nutritionists and surgeons must work together in an individualized case approach to treat this pathology and meet the expectations of the patient. Although there are various appropriate treatment modalities for each patient, the medical team must use their best judgment in selecting from among the different feasible options, in order to handle these complex scenarios.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

FUNDING

None.

References

- obesity

- drug abuse

- operative risk

- hernias

- ventral hernia

- patient care team

- greater sac of peritoneum

- preoperative care

- surgical procedures, operative

- morbidity

- mortality

- pathology

- pneumoperitoneum

- surgery specialty

- abdominal compartment syndrome

- ventral hernia repair

- interdisciplinary treatment approach

- increased body mass index