-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Yahya Alwatari, Ashley Gerrish, Dawit Ayalew, Guilherme M Campos, Jennifer L Salluzzo, Omental infarction with liquefied necrosis after Roux Y gastric bypass: case report and literature review, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2020, Issue 8, August 2020, rjaa212, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaa212

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Omental infarction is a rare phenomenon that can be idiopathic or secondary to a surgical intervention. Greater omentum division has been advocated to decrease tension at the gastro-jejunal anastomosis during laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB). We report a case of omental infraction complicated by liquefied infected necrosis presenting 3 weeks after antecolic antegastric RYGB. The patient underwent laparotomy and subtotal omentectomy with a protracted hospital course due to intra-abdominal abscesses, acute kidney injury and small bowel obstruction that were successfully managed non-operatively. We reviewed the available literature on omental infarction after RYGB, focusing on associated symptoms, possible etiology, timing of presentation, management and propose an alternative technique without omental division.

INTRODUCTION

It has been estimated that 1.9 million patients underwent bariatric surgery in the USA between 1993 and 2016, of which 27.8% were Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) [1]. Antecolic antegastric placement of the alimentary limb for the gastro-jejunal (GJ) anastomosis with RYGB has been advocated to reduce the rates of internal hernia and shorten operative time and has been the preferred technique by most [2]. One common technical step to facilitate antecolic antegastric placement of the alimentary limb and possibly reduce tension at the GJ is division of the greater omentum [3]. While it is a relatively easy maneuver, omental infarction and necrosis have been reported as a complication leading to the need for additional interventions and a protracted recovery. Our aims were to describe a case of omental infarction leading to liquefied necrosis after an uneventful laparoscopic RYGB and review the literature on the topic.

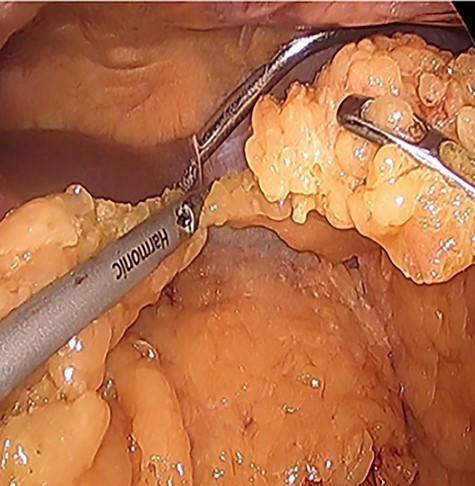

Omental division for preparation of antecolic gastrojejunostomy during index laparoscopic RYGB.

CASE REPORT

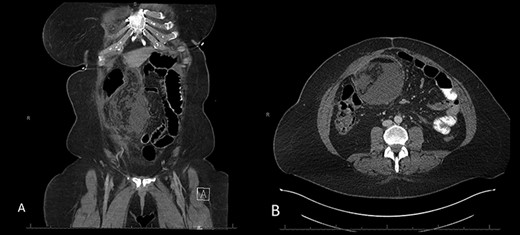

The patient is a 46-year-old female with a pre-operative body-mass index (BMI) of 48 kg/m2 who underwent an uneventful laparoscopic RYGB with a 50-cm biliopancreatic limb and 100-cm alimentary limb and an antecolic, antegastric-stapled gastrojejunostomy using a 21–3.5-mm circular stapler in addition to the repair of a small sliding hiatal hernia. A thick omentum was divided in the midline, starting at the level of the mid-portion of the transverse colon moving distally through the edge of the omentum (Fig. 1). The procedure was uneventful, and the patient was discharged home on postoperative day 1. She had a scheduled follow-up visit at 2 weeks and was progressing as expected. Three weeks postoperatively, she presented to the emergency room complaining of two-day history of severe, diffuse abdominal pain. Initial vital signs were normal and laboratory values were WBC of 6.7 109/L, creatinine 0.76 mg/dl and lactate of 1.2 mmol/L. CT scan was obtained (Fig. 2A and B) that demonstrated 17.7 cm partially encapsulated mixed attenuating area on the right side of her abdomen, suggestive of omental infarction with necrosis. There was no evidence of leak from GJ or JJ anastomoses on CT with oral contrast, which was subsequently confirmed on upper GI with small bowel through. She was admitted for observation. Over the course of the next day, she reported worsening abdominal pain and developed tachycardia to 117 and BP of 89/68 mmHg. Repeat WBC count was 12.7 109/L, creatinine 1.29 mg/dl and lactate of 5.0 mmol/L.

A and B: Abdominal and pelvic CT scan obtained at POD # 21 readmission for abdominal pain showing a 17.7-cm mixed attenuating lesion extending anterior to the transverse colon into the upper-pelvis-associated stranding and fluid level suggestive of omental infarction and liquefied necrosis.

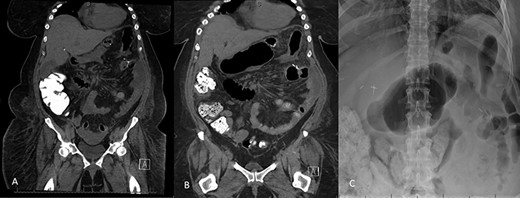

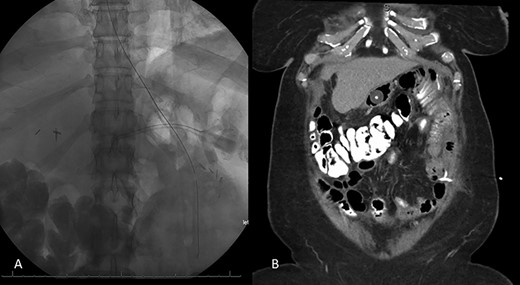

Decision was made to explore and attempt to excise the infarcted omentum. She was taken to the operating room and underwent a diagnostic laparoscopy. However, due to the large size of the omental infarction with an encapsulated necrotic liquefied, purulent secretion and significant adhesions, we decided to convert it to a midline laparotomy. We then proceeded with resection of right-sided infarcted, necrotic, liquefied omentum and abdominal washout (Fig. 3). Culture from the purulent secretion that was inside encapsulated omentum grew Streptococcus anginosus. She received Meropenem and Fluconazole. She had a prolonged and protracted recovery with a transient kidney injury and the development of multiple intra-abdominal (inter-loop, peri-hepatic, peri-splenic and pelvic) fluid collections (Fig. 4A). These collections were treated by percutaneous drainage (pelvis × 1, perisplenic and left-sided collections × 2). Three weeks from the take back, she developed a small bowel obstruction with significant dilation of the biliopancreatic limb and excluded stomach (Fig. 4B and C). She was taken to the operating room and had an endoscopically placed nasogastric tube just passed the jejunojejunostomy. Then, she underwent CT-guided gastrostomy tube to decompress in the gastric remnant (Fig. 5 A and B). One week after the rendezvous nasogastric and gastric remnant decompression, an oral and through the G-tube contrast study demonstrated patency of the gastrojejunostomy and resolution of the small bowel obstruction (Fig. 6). The patient was discharged home on POD #39 tolerating a regular postbariatric surgery diet.

Resected infarcted omentum with central necrotic cavity and liquefied fat and purulent fluid.

A: Abdominal and pelvic CT scan obtained at POD # 29. From index RYGB and POD # 8 from excision of infarcted omentum showing loculated perisplenic, pelvic and perihepatic fluid collections. B and C: Abdominal and pelvic CT scan obtained at POD # 20 from take back and plain X-ray showing gaseous distention of the excluded stomach and duodenum, confirming a small bowel obstruction of the biliopancreatic limb.

Resolution of small bowel obstruction. A: Plain X-ray at POD # 25 from take back showing endoscopically placed nasogastric tube placement near JJ anastomosis B: Abdominal and pelvic CT scan showing percutaneous gastrostomy tube within the excluded stomach and pigtail catheter in the left hemiabdomen.

Follow-up abdominal and pelvic CT scan at POD # 35 with interval resolution of intra-abdominal abscess and small bowel obstruction.

DISCUSSION

Omental infarction is a very rare disease with an estimated incidence of (0.001–0.3%) [4]. It can be classified as idiopathic (primary) or secondary. Development of omental infarction is more common in children with a predilection for right-sided omental infarctions and heavily fat-laden omentum being a risk factor [5]. Management options are variable ranging from conservative management with pain control in ED to source control with IR drainage vs. omental resection based on the patient presentation and extent of infarction [6].

Table 1 summarizes the reported cases of omental infarction after RYGB. About, 60% of the patients were female with a mean age of 45 years and BMI of 47 kg/m2. Procedures were done laparoscopically with the antecolic approach. Timing of presentation with omental infarction was variable ranging from postoperative day 3 to 11 years. The majority of patients presented with localized abdominal pain without systemic signs. CRP was elevated in cases that reported its value. One patient developed perihepatic, right paracolic and pelvic fluid collections [7]. With the exception of one, all the patients required surgical exploration and partial omental resection. Appendectomy was performed in two cases.

| Author/Year | Surgical techniques | Presentation | Patients demographics | Timing | Management |

| Dallal et al. (2006) Case study | Laparoscopic Antecolic Proximal to distal omental transaction | Acute, localized abdominal pain. No significant signs of systemic illness | Three patients Two females Mean age 48 Mean BMI 48 | POD 3 | Laparoscopic re-exploration and segmental omental resection |

| Campos et al. (2007) Cohort study | Laparoscopic Antecolic | Abdominal pain and leukocytosis | POD 21 | Laparoscopic re-exploration and segmental omental resection | |

| Auguste et al. (2008) Case report | Not available | Acute severe epigastric pain with signs of localized peritoneal irritation | 56 yo F | POD 25 | Conservative management |

| Bestman et al. (2009) Case report | Laparoscopic Antecolic | Severe epigastric and right upper | 41 yo M BMI 43 | 1 year Post op. | Partial laparoscopic omentectomy |

| Quadrant pain. N annal WBC. No systemic signs | |||||

| Alsulaimy et al. (2016) Case report | Laparoscopic Antecolic | Diffuse abdominal tenderness with rebound. Leukocytosis of 18.6 × 103/L | 58 yo F | 4 months Post op. | Emergent diagnostic Laparoscopy and partial omental resection |

| Descloux et al. (2016) Case report | Laparoscopic Antecolic | R lower quadrant abdominal pain + McBurney's Normal WBC Moderate elevation in CRP | 31 yo F BMI 50.3 | 2 years Post op. | Laparoscopic resection of necrotic omentum and appendectomy |

| Martin et al. (2017) Case report | Laparoscopic Antecolic | Abdominal pain in the right flank Antecolic leukocytosis and a high CRP | 39 yo M BMI 41 | POD 6 | Exploratory Laparoscopy with abscess drainage and washout |

| Abrisqueta et al. (2017) Case report | Laparoscopic Antecolic | Pain in the right iliac fossa Elevated C-reactive protein levels and no leukocytosis | 32 yo F BMI 52 | 11 years Post op. | Partial laparoscopic Omentectomy and appendectomy |

| Author/Year | Surgical techniques | Presentation | Patients demographics | Timing | Management |

| Dallal et al. (2006) Case study | Laparoscopic Antecolic Proximal to distal omental transaction | Acute, localized abdominal pain. No significant signs of systemic illness | Three patients Two females Mean age 48 Mean BMI 48 | POD 3 | Laparoscopic re-exploration and segmental omental resection |

| Campos et al. (2007) Cohort study | Laparoscopic Antecolic | Abdominal pain and leukocytosis | POD 21 | Laparoscopic re-exploration and segmental omental resection | |

| Auguste et al. (2008) Case report | Not available | Acute severe epigastric pain with signs of localized peritoneal irritation | 56 yo F | POD 25 | Conservative management |

| Bestman et al. (2009) Case report | Laparoscopic Antecolic | Severe epigastric and right upper | 41 yo M BMI 43 | 1 year Post op. | Partial laparoscopic omentectomy |

| Quadrant pain. N annal WBC. No systemic signs | |||||

| Alsulaimy et al. (2016) Case report | Laparoscopic Antecolic | Diffuse abdominal tenderness with rebound. Leukocytosis of 18.6 × 103/L | 58 yo F | 4 months Post op. | Emergent diagnostic Laparoscopy and partial omental resection |

| Descloux et al. (2016) Case report | Laparoscopic Antecolic | R lower quadrant abdominal pain + McBurney's Normal WBC Moderate elevation in CRP | 31 yo F BMI 50.3 | 2 years Post op. | Laparoscopic resection of necrotic omentum and appendectomy |

| Martin et al. (2017) Case report | Laparoscopic Antecolic | Abdominal pain in the right flank Antecolic leukocytosis and a high CRP | 39 yo M BMI 41 | POD 6 | Exploratory Laparoscopy with abscess drainage and washout |

| Abrisqueta et al. (2017) Case report | Laparoscopic Antecolic | Pain in the right iliac fossa Elevated C-reactive protein levels and no leukocytosis | 32 yo F BMI 52 | 11 years Post op. | Partial laparoscopic Omentectomy and appendectomy |

| Author/Year | Surgical techniques | Presentation | Patients demographics | Timing | Management |

| Dallal et al. (2006) Case study | Laparoscopic Antecolic Proximal to distal omental transaction | Acute, localized abdominal pain. No significant signs of systemic illness | Three patients Two females Mean age 48 Mean BMI 48 | POD 3 | Laparoscopic re-exploration and segmental omental resection |

| Campos et al. (2007) Cohort study | Laparoscopic Antecolic | Abdominal pain and leukocytosis | POD 21 | Laparoscopic re-exploration and segmental omental resection | |

| Auguste et al. (2008) Case report | Not available | Acute severe epigastric pain with signs of localized peritoneal irritation | 56 yo F | POD 25 | Conservative management |

| Bestman et al. (2009) Case report | Laparoscopic Antecolic | Severe epigastric and right upper | 41 yo M BMI 43 | 1 year Post op. | Partial laparoscopic omentectomy |

| Quadrant pain. N annal WBC. No systemic signs | |||||

| Alsulaimy et al. (2016) Case report | Laparoscopic Antecolic | Diffuse abdominal tenderness with rebound. Leukocytosis of 18.6 × 103/L | 58 yo F | 4 months Post op. | Emergent diagnostic Laparoscopy and partial omental resection |

| Descloux et al. (2016) Case report | Laparoscopic Antecolic | R lower quadrant abdominal pain + McBurney's Normal WBC Moderate elevation in CRP | 31 yo F BMI 50.3 | 2 years Post op. | Laparoscopic resection of necrotic omentum and appendectomy |

| Martin et al. (2017) Case report | Laparoscopic Antecolic | Abdominal pain in the right flank Antecolic leukocytosis and a high CRP | 39 yo M BMI 41 | POD 6 | Exploratory Laparoscopy with abscess drainage and washout |

| Abrisqueta et al. (2017) Case report | Laparoscopic Antecolic | Pain in the right iliac fossa Elevated C-reactive protein levels and no leukocytosis | 32 yo F BMI 52 | 11 years Post op. | Partial laparoscopic Omentectomy and appendectomy |

| Author/Year | Surgical techniques | Presentation | Patients demographics | Timing | Management |

| Dallal et al. (2006) Case study | Laparoscopic Antecolic Proximal to distal omental transaction | Acute, localized abdominal pain. No significant signs of systemic illness | Three patients Two females Mean age 48 Mean BMI 48 | POD 3 | Laparoscopic re-exploration and segmental omental resection |

| Campos et al. (2007) Cohort study | Laparoscopic Antecolic | Abdominal pain and leukocytosis | POD 21 | Laparoscopic re-exploration and segmental omental resection | |

| Auguste et al. (2008) Case report | Not available | Acute severe epigastric pain with signs of localized peritoneal irritation | 56 yo F | POD 25 | Conservative management |

| Bestman et al. (2009) Case report | Laparoscopic Antecolic | Severe epigastric and right upper | 41 yo M BMI 43 | 1 year Post op. | Partial laparoscopic omentectomy |

| Quadrant pain. N annal WBC. No systemic signs | |||||

| Alsulaimy et al. (2016) Case report | Laparoscopic Antecolic | Diffuse abdominal tenderness with rebound. Leukocytosis of 18.6 × 103/L | 58 yo F | 4 months Post op. | Emergent diagnostic Laparoscopy and partial omental resection |

| Descloux et al. (2016) Case report | Laparoscopic Antecolic | R lower quadrant abdominal pain + McBurney's Normal WBC Moderate elevation in CRP | 31 yo F BMI 50.3 | 2 years Post op. | Laparoscopic resection of necrotic omentum and appendectomy |

| Martin et al. (2017) Case report | Laparoscopic Antecolic | Abdominal pain in the right flank Antecolic leukocytosis and a high CRP | 39 yo M BMI 41 | POD 6 | Exploratory Laparoscopy with abscess drainage and washout |

| Abrisqueta et al. (2017) Case report | Laparoscopic Antecolic | Pain in the right iliac fossa Elevated C-reactive protein levels and no leukocytosis | 32 yo F BMI 52 | 11 years Post op. | Partial laparoscopic Omentectomy and appendectomy |

The pathogenesis behind post-RYGB omental infarction and necrosis is unknown. Several possibilities have been described including asymmetric omental division, torsion secondary to adhesive disease or internal hernia resulting in compromised vascular supply to the omental leaflets [8]. Selective omental resection during RGYB had been advocated by some to improve postoperative glucose metabolism [9]; however, this has not been proven to provide benefit and could be associated with this complication.

Diagnosis of omental infarction can be challenging as presentation can be delayed and confused with anastomotic leak, internal hernia or appendicitis. A unique and rare finding in our patient was the infected liquefied necrosis of the omentum, which after resection lead to the development of multiple intra-abdominal abscesses. One technical modification that has been proposed to prevent omental infraction is to avoid dividing the omentum and translocate it from left to right of the abdomen to allow bringing the antecolic alimentary limb. While decreasing the risk for omental infarction, this maneuver may increase tension at GJ anastomosis especially in cases of thick omentum.

In conclusion, secondary omental infarction is a rare complication after laparoscopic antecolic RYGB and has a variable time to presentation. All but one of the 10 published cases required surgical resection. Avoidance of omental transection may prevent this complication.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

Drs Alwatari, Gerrish, Ayalew were responsible for drafting the report and conducting literature review. Drs Campos and Salluzzo supervised writing manuscript. All authors contributed to drafting the manuscript and/or revising it critically.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

FUNDING

None.