-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Conor Brosnan, Shane Keogh, Jarlath C Bolger, Kevin Farrell, Enda Hannan, Doug Mulholland, Abeeda Butt, Arnold D K Hill, Emergency surgery in an elective setting: a case report detailing incidental diagnosis of a de Garengeot hernia, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2020, Issue 6, June 2020, rjaa164, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaa164

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

We present a case of acute appendicitis within an incarcerated femoral hernia. This is a rare complication of the phenomenon eponymously known as a ‘De Garengeot Hernia’, which describes a vermiform appendix in an incarcerated femoral hernia sac. Our case is somewhat unique in the manner by which the affected patient had presented. Attending hospital for an unrelated elective surgery, an incarcerated hernia was diagnosed at time of admission. Thorough assessment in advance of the procedure and decisive action led to a satisfactory outcome. This may be the first case in literature reporting a ‘De Garengeot Hernia’ presenting in such a fashion.

INTRODUCTION

Three to five percent of all abdominal hernias are femoral. They account for 20% of all groin hernias in women but under 1% in men and result from abdominal contents extending through the femoral ring into the femoral canal [1]. Femoral hernias commonly present in an emergency setting. They can rapidly become irreducible and have a very high risk of strangulation, secondary to the tightness of the hernia neck. Presence of the appendix in a femoral hernia sac was first described in 1731 and is eponymously known as a ‘de Garengeot hernia’ (DGH) [2]. Less than 100 cases have been reported in literature since. Additional appendicitis within a femoral hernia is an even rarer finding, seen in only 0.08–0.13% of cases [3, 4].

The mechanism of appendiceal migration into a femoral hernia sac is unknown. It may be caused by abnormal midgut rotation during embryogenesis, increased cecal size, inflammation of the appendix itself or a combination of all the above [5]. Femoral hernias are at high risk of incarceration and subsequent strangulation owing to the tightly fixed arrangement of the femoral ring and its narrow opening. DGHs follow this principle. Patients rarely present with constitutional symptoms or peritonitis, which may also be explained by this anatomical arrangement. Sac contents are somewhat isolated from the peritoneal cavity due to the narrow hernial neck that acts as a physical barrier to spread of localized ischemia and necrosis. This can delay presentation and lead to poorer prognoses.

We report a case of DGH incidentally detected during admission for an unrelated elective surgical procedure. The hernia was only detected during a systems review. Subsequent intervention revealed a necrotic appendix within the hernia sac, which was removed. We believe our case to be unique in the clinical course described. It highlights the importance of thorough clinical history taking and examination. This allowed successful emergency management of a particularly rare phenomenon in what had appeared to be an elective setting.

CASE REPORT

A 76-year-old female presented to hospital for an elective right-sided mastectomy and axillary lymph node clearance as management of a clinically node positive, triple negative, invasive ductal carcinoma diagnosed a month prior. A thorough history was taken at admission and the patient reported a ‘sore lump’ in her right groin on systems review. This appeared 2 days previously. She was hemodynamically stable, afebrile and generally well. Focused examination revealed a 2 × 2cm swelling inferolateral to the pubic tubercle, with overlying erythematous skin. This was tender and irreducible, with a positive cough impulse noted.

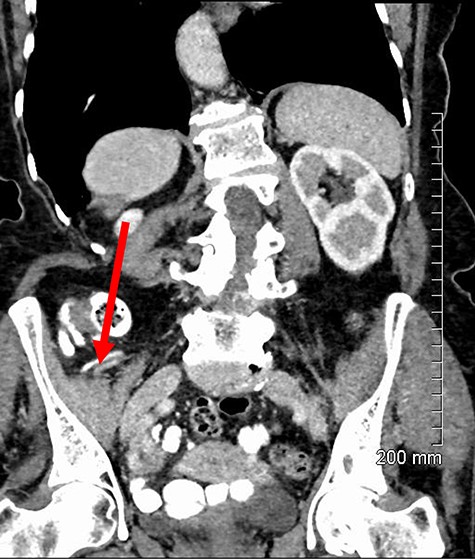

An incarcerated femoral hernia was diagnosed clinically and previous hematological investigations and imaging studies were reviewed. Full blood count, urea and electrolytes and liver function tests were within normal limits. Inflammatory markers including C-reactive protein had not been tested for preoperatively. The patient’s staging computed tomography (CT) thorax, abdomen and pelvis (performed a month before surgery) had shown fluid in the right inguinal region, appearing to lie within a small hernia (Fig. 1). A decision was made by the treating team to proceed with a joint procedure. The patient was consented for simultaneous mastectomy with axillary clearance and hernia repair.

Axial contrast-enhanced CT showing hernial sac containing fat and simple fluid but no appendix (red arrow).

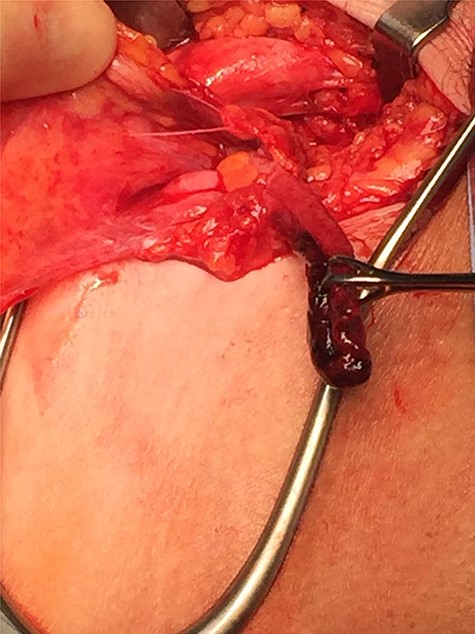

Repair was performed via a transinguinal (Lotheissen’s) approach. An incision was made just superior to the inguinal ligament and a femoral hernia was identified. The sac was dissected free and opened, revealing a gangrenous appendix (Fig. 2). There had been no preoperative suspicion for appendiceal involvement or strangulated contents, with normal lab studies and the appendix located remotely from the hernia on previous imaging (Fig. 3). The diagnosis of DGH was made intraoperatively. Abdominal access was achieved through the initial incision to facilitate an open appendicectomy. The mesoappendix and base of the appendix were ligated with sutures and delivered for further histology. The hernia sac was then transfixed and excised. A primary repair was performed with a non-absorbable suture.

Gangrenous appendix revealed following opening of femoral hernia sac.

Sagittal contrast-enhanced CT showing a retrocecal appendix (red arrow) discreet from the observed hernia.

The patient had an uneventful post-operative course. She was discharged on day 2 post-op and remained well attending the outpatient clinic 6 weeks later. Histology showed gangrenous appendicitis and she required no further follow up.

DISCUSSION

DGH is extremely rare. Incarceration, inflammation and strangulation of contents are common and serious complications. Sequelae can progress rapidly, owing to the tight femoral ring and limited space in the femoral canal. Diagnosis of DGH is exceptionally difficult. Patients present with signs and symptoms typical of a general incarcerated femoral hernia which overshadow classical signs and symptoms of acute appendicitis. There are no specific laboratory findings for DGH while radiological tests have poor sensitivity. Ultrasound is unreliable, while the sensitivity of CT is reported to be as low as 44% [6].

Given the rarity of appendicitis within a femoral hernia, there is no defined standard of care for this phenomenon. Published approaches include open drainage and subsequent appendicectomy and hernia repair, initial appendicectomy and interval hernia repair and simultaneous appendicectomy and hernia repair. Absence of appendicitis may facilitate simple reduction of the appendix and hernia repair only. Choice of operative technique is guided by surgeon preference. Three classical initial approaches are described. They include Lockwood’s infrainguinal approach, Lotheissen’s transinguinal approach and McEvedy’s high approach. A transinguinal approach was performed in this case, which allowed for both hernia repair and appendicectomy through a single incision. Laparoscopic approaches are controversial in management of incarcerated femoral hernias. Successful laparoscopic repair of DGH has previously been described but this also controversial owing to the difficulty in preoperative diagnosis of the phenomenon. Laparoscopic repair of DGH would require the less common transabdominal preperitoneal approach instead of a totally extraperitoneal approach as the peritoneal cavity must be accessed to evaluate/obtain access to the appendix.

This case reports an exceptionally rare phenomenon presenting in an unusual setting. To our knowledge, this is the first report of DGH presenting in such a fashion. The patient had neglected to inform clinicians of her groin lump until directly asked. A well-taken history and examination allowed for early diagnosis and treatment. The patient may have had a much poorer outcome if this had not been recognized until a later stage.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None to declare.

REFERENCES