-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Iroukora Kassegne, Tabana Essohanam Mouzou, Kokou Kanassoua, Tamegnon Dossouvi, Yawod Efoé-Ga Amouzou, Aboza Sakiye, Komlan Adabra, Fousseni Alassani, Ayi Kossigan Amavi, Boyodi Tchangai, Ekoué David Joseph Dosseh, Severe snakebite envenomation revealed by an acute abdomen, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2020, Issue 6, June 2020, rjaa148, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaa148

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Acute abdomens are common conditions, with many aetiologies in developing countries. Abdominal bleeding due to snake envenomation is an extremely rare aetiology. A 11-year-old girl was admitted for acute abdominal pains. She had a history of foot bite of unknown origin. Physical examination revealed palor and abdominal tenderness. At laparotomy, there were peritoneal and retroperitoneal diffuse hematomas. Laboratory studies revealed abnormal coagulation profile. Retroperitoneal and peritoneal hematomas’ diagnosis, by consumptive coagulopathy, due to snakebite envenomation, was made. Polyvalent antivenom administration permitted a normalization of coagulation profile, however, with persistent surgical site bleeding. Whole blood transfusion was administered with bleeding stop. Sudden abdominal pain, palor and signs of peritonism suggest an acute abdomen. However, abdominal bleeding due to snakebite envenomation should be considered, especially in child with unidentified bite history. Imaging modalities may helpful to confirm the abdominal bleeding. Antivenom is the mainstay of the treatment.

Introduction

Snakebite envenomation is a worldwide problem, which is an important cause of death in the developing countries and still remains a neglected public health problem [1]. It may cause different clinical features varying from no signs, moderate to severe and depending on the involved snake species [2]. Its diagnosis is problematic when the snakebite is unidentified.

Recently, we experienced a female child, managed for snakebite envenomation, diagnosed pre-operatively. This case report presents a rare case of severe snakebite envenomation, revealed by an acute abdomen. To our knowledge, such a case of snakebite envenomation diagnosis has not been reported previously.

Case Report

A 11-year-old girl presented with acute abdominal pains for 2 days. She did not experience fever or digestive symptoms (vomiting, constipation, diarrhea and blood in stool). There was neither history of abdominal trauma nor hemophilia. Her blood pressure was 90/50 mm Hg, her heart rate was 130 beats/minute and her temperature was 36.5°C. Physical examination revealed severe palor and severe abdominal tenderness.

Emergency preoperative laboratory studies available revealed a decrease of hemoglobin level (4 g/dl). White blood cells count and kidney function were normal. Platelet count, coagulation profile, liver function, amylase level, abdominal ultrasonography and computed tomography were not performed.

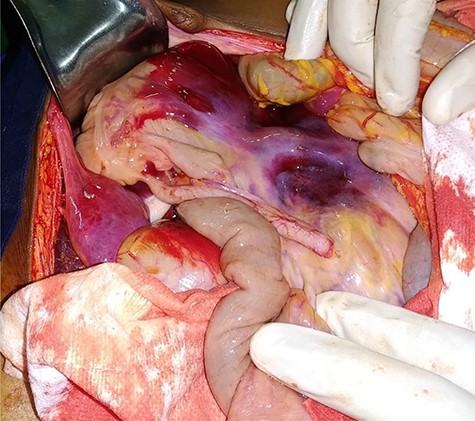

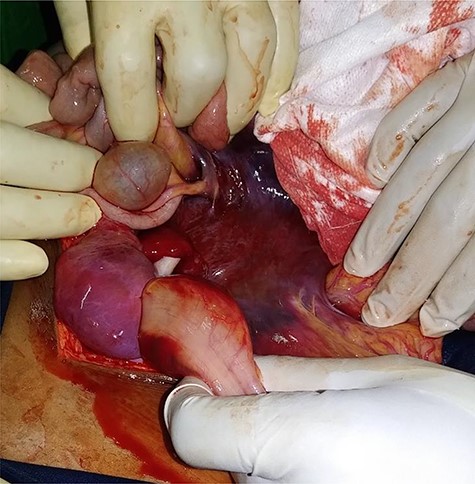

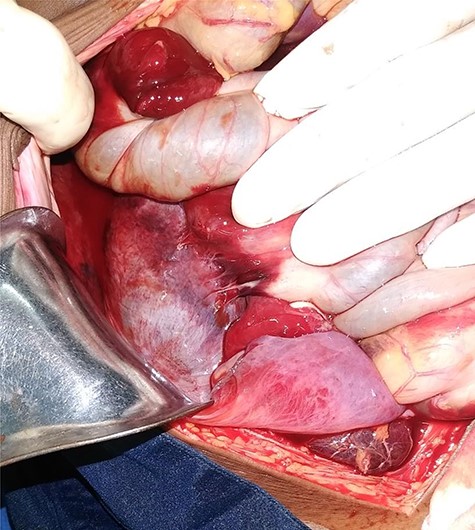

A diagnosis of generalized peritonitis was made. Resuscitation was started immediately with three units (750 ml) of packed red cells transfusion. Emergency laparotomy exploration was planned. Intra-operatively, there were mesenteric (Fig. 1), mesocolic (Fig. 2), mesosigmoid (Fig. 3) and right Toldt’s fascia (Fig. 4) diffuse hematoma. The adjacent bowels had no inflammatory nor ischemia changes. There was neither peritonitis nor intraperitoneal free fluid. There was no mesenteric lymph node. Other abdominal organs were essentially normal. No surgical act was performed. There was surgical site diffuse bleeding.

Laboratory studies revealed on Day 1, abnormal coagulation profile: quadrupled prothrombin time (PT) and prolonged activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT) at 1.45. The platelet count was 46 000/ml and hemoglobin was 5 g/dl.

In retrospective questioning, our patient reported a history of right foot bite of unknown origin, 10 days before admission. Physical examination of the right foot was normal (no edema nor necrosis). Postoperative diagnosis of retroperitoneal hematoma, and peritoneal hematoma, by consumptive coagulopathy, probably due to snakebite envenomation, was made.

Transfusion of two units (500 ml) of packed red cells and two doses of polyvalent snake antivenom (Inoserp™ Panafricain) were administered. Fresh frozen plasma was not administered. The treatment permitted a normalization of coagulation profile (PT and APTT were normal), however, with persistent surgical site bleeding. The platelet count was normalized (164 000 per ml) and the hemoglobin was 7 g/dl. Another two doses of polyvalent snake antivenom (Inoserp™ Panafricain) and 500 mL of whole blood transfusion were administered, with surgical site bleeding stop, achieving 24 hours later. The patient was discharged 7 days after the laparotomy.

Discussion

Snakebite envenomations are mostly due to viperidae snakes, in tropical parts of the world [3]. The viperidae snakes are responsible for viperin syndrom, which associate local syndrom (pain, edema and necrosis) and hemostasis disorders. Hemostasis disorders cause local and diffuse bleedings, due to venom-induced consumption coagulopathy (VICC) [4]. Viperidae snakes release a mixture of enzymes and polypeptide toxins [5] that cause an activation of the coagulation pathway by prothrombin activator toxins and consumption of blood coagulation factors that lead to a consumptive coagulopathy [2].

Beside the massive envenomation leading to early hemorrhage, the course of the envenomation evolves slowly. In frequent cases, envenomation is limited to a dramatic decrease in blood coagulation factors without clinical manifestations. The first systemic hemorrhage signs can possibly show from several days after snakebite, especially if treatment is delayed [3].

In our patient, snakebite envenomation diagnosis was made, with the foot bite history, the diffuse abdominal and surgical site bleedings, abnormal coagulation profile and their normalizing after snake antivenom administration.

Ultrasonography and computed tomography were not performed, because of their unavailability in emergency and the patient precarious hemodynamic status. It is important to emphasize that laparotomy could have been avoided by careful pre-operative examination including ultrasonography, a method that would have enabled diagnose preoperatively abdominal bleeding and that should be available to all emergency units dealing with acute abdominal conditions. If no radiologist is 24 × 7 present, then the emergency room physician or surgeon should master this technique.

Snake antivenom remains the mainstay in combating envenomation of snake and preventing complications arising from them [6, 7]. In children, it is recommended for any snakebite envenomation, even moderate. It should be given as soon as possible but can be effective even when administered several days after the snakebite [3]. It permits to neutralize effectively the venon toxins, responsible for blood coagulation factors consumption [4]. Doses of snake antivenom on patients depend on the envenomation severity, clinical outcome, laboratory studies of coagulation profile and antivenom specificity and neutralizing effect [2, 3].

In case of dramatic hemostasis disorders as noted in our patient, the only blood coagulation factors perfusion cannot permit to obtain a normalization of coagulation profile. As soon as perfused, these factors are consumed by the venom’s enzymes contained in the patient’s blood [3]. Combination of snake antivenom with fresh frozen plasma allows to more rapidly stop VICC [4]. In our patient, persistent surgical site bleeding and fresh frozen plasma unavailability had prompted us to make whole blood transfusion. This blood transfusion had brought consumed blood coagulation factors, essential for achieving a complete bleeding stop.

In summary, the occurrence of sudden abdominal pains, severe anaemia and signs of peritonism, without history of hemophilia or abdominal trauma, should suggest an acute abdomen as the first diagnostic option. However, abdominal diffuse bleeding due to snakebite envenomation should be borne in mind in the differential diagnosis of this condition, especially in child patients with history of unidentified bite, in previous days before. Imaging modalities including ultrasound and computed tomography are helpful to confirm the diagnosis of abdominal bleeding. The snake antivenom is the only aetiological treatment. It should be combined with blood coagulation factors.

Written patient consent is available.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

None.

Conflict of interest

None.