-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Kyle Litow, Gaby Jabbour, Alexandra Bahn-Humphrey, Christy Stoller, Peter Rhee, Rifat Latifi, Kartik Prabhakaran, Gregory Veillette, Curative resection of a duodenal gastrointestinal stromal tumor in the setting of von Willebrand’s disease, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2020, Issue 4, April 2020, rjaa081, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaa081

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) is the most common mesenchymal tumor of the alimentary tract and usually presents with gastrointestinal hemorrhage. The diagnosis of GIST is typically made with upper endoscopy after excluding other causes of bleeding. The surgical management of GIST can be challenging depending upon the location of the tumor. We present a unique case of duodenal GIST in the setting von Willebrand’s disease diagnosed after emergent laparotomy for massive gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Key strategies in curing our patient were treating the underlying bleeding disorder, collaborating with radiology and gastroenterology teams, and early exploratory laparotomy for refractory hemorrhage. This case demonstrates the challenges of diagnosing and managing GIST in patients with underlying coagulopathies.

INTRODUCTION

Gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) is the most common mesenchymal tumor of the alimentary tract and usually presents with gastrointestinal hemorrhage [1]. We present a unique case of duodenal GIST in the setting von Willebrand’s disease diagnosed after emergent laparotomy for massive gastrointestinal hemorrhage. This case demonstrates the challenges of diagnosing and managing GIST in patients with underlying coagulopathies.

(a and b): CT angiography with axial and coronal views demonstrating intraluminal duodenal hemorrhage (arrow) and hemorrhagic duodenal mass (arrowhead).

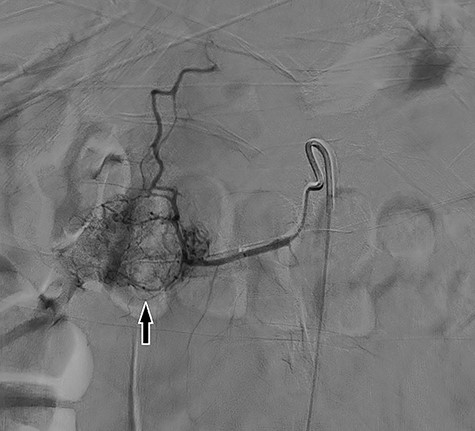

Digital subtraction angiography demonstrating large inferior pancreaticoduodenal arcade with superior reconstitution of the gastroduodenal artery and common hepatic artery and represents region of mass in without active contrast extravasation.

CASE REPORT

Our patient is a 30-year-old female with a past medical history of von Willebrand’s disease, bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder, anxiety and opioid abuse who presented to our hospital for right-sided abdominal pain and blood per rectum. She experienced massive hematemesis in the emergency department with blood pressure 98/55 mmHg, heart rate 145 bpm and respiratory rate 18 breaths per minute. Hemoglobin and hematocrit levels were 3.2 g/dl and 9.5%, respectively, and lactate level was 7.0 mmol/l. She promptly received 4 units of packed red blood cells with improvement of vital signs. Initial computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis was negative for intra-abdominal pathology. Therefore, she was taken for emergent endoscopy. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy revealed an ulcerative mass of the second portion of the duodenum with overall poor visualization secondary to bleeding; biopsies were taken. Concomitant flexible sigmoidoscopy revealed blood in the rectum with no other pathologic findings. Emergency CT angiogram was performed revealing active hemorrhage into the duodenum (Fig. 1). The patient was admitted to the surgical intensive care unit where she underwent placement of resuscitative lines. Hemoglobin and hematocrit levels were 3.9 g/dl and 10.1% despite initial resuscitation and the patient was further transfused 6 units packed red blood cells, 2 pools of cryoprecipitate, 4 pools of platelets and 5 units of plasma; 1 g of tranexamic acid was given every 8 hours for 2 days. Per hematology recommendations, von Willebran factor/factor VIII complex (Humate-P) and desmopressin (1-deamino-8-D-arginine vasopressin, DDAVP) were administered. The patient underwent emergent mesenteric angiography by interventional radiology that revealed extensive vascular arcades at the second portion of the duodenum from the inferior pancreaticoduodenal artery without active extravasation (Fig. 2). The patient’s inappropriate response to multiple blood products necessitated emergent surgical exploration. Midline laparotomy revealed no gross hemoperitoneum. The hepatic flexure was mobilized and a Kocher maneuver was performed, revealing an ulcerative duodenal mass at the second portion of the duodenum. A longitudinal duodenotomy allowed for localization of an actively hemorrhaging mass 5 mm distal to the hepatopancreatic ampulla. The ampulla was cannulated with a pediatric feeding tube to mark its location during tumor resection. A wedge resection of the hemorrhagic duodenal mass was performed, including a small portion of nearby pancreatic head parenchyma. Hemostasis and preservation of bile flow through the ampulla was confirmed. The duodenotomy was hand-sewn in two layers transversely. A surgical drain was placed at the site of duodenal resection. The patient remained hypotensive and hypothermic, leading to a decision to institute damage control measures with temporary abdominal closure using a negative pressure wound therapy device. After further resuscitation and stabilization, the patient was brought back to the operating room 2 days later for planned re-exploration and definitive abdominal wall closure. Her postoperative recovery was complicated by a superficial incisional surgical-site infection that was treated successfully with drainage and a negative pressure wound therapy device, and she was discharged on hospital Day 22. Final surgical pathology revealed duodenal GIST measuring 2.5 × 2.0 × 1.4 cm with negative margins and no lymph nodes, corresponding to a pT2 tumor per the American Joint Committee on Cancer grading system. The GIST was mixed spindle and epitheliod type, CD117, CD34 and DOG 1 positive and CK7, AE1/AE3, synaptophysin and actin negative. The tumor had low mitotic rate, histologic Grade 1 with a Ki-67 index <5% and deemed low risk for recurrence. Due to the clinical and immunohistologic findings, observation without tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy was the chosen management strategy. One-month follow-up was unremarkable and without symptoms of ongoing bleeding or recurrence.

DISCUSSION

Our case exemplifies the challenges faced by a surgical team when diagnosing and managing hemorrhagic GIST with underlying von Willebrand’s disease. In our case, a complete preoperative workup was precluded by life-threatening hemorrhage requiring emergency laparotomy. At the time of laparotomy, the diagnosis was not clearly established; the primary goal of the operation was safe resection of the actively bleeding mass and hemostasis. Standard treatment of a GIST without metastasis is surgical resection, and our operation was both diagnostic and curative [1].

GIST may directly invade adjacent tissues or organs, spread to distant organs hematogenously or metastasize to the liver or the omentum via peritoneal dissemination. Lymphatic spread of GIST, however, is extremely rare (1%), and routine lymphadenectomy is not recommended [4]. No lymph nodes were present in our specimen. GIST may occur at any age, with the most common age group at diagnosis being 60–69 years with a slight male predominance [3]. GIST is very uncommon in our patient’s age group. A population-based study showed that only 6% of GIST present below the age of 40 [3]. The most common location of GIST (~60%) in the gastrointestinal tract is the stomach, followed by the small bowel (~35%) [3]. Our patient’s tumor was located in the second portion of the duodenum. Fortunately, the tumor did not involve the hepatopancreatic ampulla, which was successfully cannulated intraoperatively. This allowed for safe resection and primary closure of the duodenum.

To our knowledge, this represents the first reported case of duodenal GIST in the setting of von Willebrand’s disease. Von Willebrand’s disease is the most common inherited bleeding disorder [2]. Our patient was administered desmopressin and von Willebrand factor concentrates in conjunction with blood products, in accordance with current recommendations [2]. Prompt surgical exploration in our patient for refractory hemorrhage allowed for hemostatis and establishment of a definitive diagnosis. A multidisciplinary approach to the abdominal exploration was employed by the general surgery and hepatobiliary surgery teams. Key strategies in curing our patient were treating the underlying bleeding disorder, collaborating with radiology and gastroenterology teams, and early exploratory laparotomy for refractory hemorrhage.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Westchester Medical Center, Department of Surgery and New York Medical College.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

There are no financial conflicts of interest to disclose.