-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Ashali Jain, Anthony Azzolini, Seth Kipnis, A unique presentation of perforated duodenal ulcer in a postpartum woman: a case report, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2020, Issue 12, December 2020, rjaa459, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaa459

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Gallbladder disease and peptic ulcer disease (PUD) can present very similarly, and misdiagnosis can often result because of conflicting symptoms. PUD in pregnancy is relatively rare, in part due to the changes in estrogen and progesterone levels. We present a case of a postpartum female, post operation Day 5, with signs/symptoms, physical exam and laboratory work consistent with acute cholecystitis that was found to have a perforated duodenal ulcer intraoperatively. The authors suggest that a fistula would have resulted with ongoing disease. Bilio-enteric fistulas can often form due to ongoing cholelithiasis disease. Cholecystoduodenal fistulas (CDFs) are the most common fistulas to present. It is possible that the incidence of CDF formation secondary to perforated duodenal ulcers is underestimated due to signs and symptoms not presenting until gallstone ileus is diagnosed.

INTRODUCTION

The case presented is unique in that the presentation was a misdiagnosis of cholecystitis in a 5 days postpartum woman with a perforated duodenal ulcer. The perforated segment of duodenum adhered to the gallbladder, effectively ‘patching’ the perforation. The gallbladder wall showed signs of erosion, indicating the early phases of forming a cholecystoduodenal fistula (CDF).

CASE REPORT

A 34-year-old, G2P3 woman postoperative Day 5 from a cesarean section delivery presented to the ED at our institution with a chief complaint of right upper quadrant (RUQ) abdominal pain. The patient described RUQ pain since the C-section, worse after meals. The pain acutely worsened 24 h prior to arrival. It did not radiate and was unlike pain she had experienced in the past. She attributed the worsening pain to gas; however, it did not resolve. She began having nausea and vomiting on the night prior to arrival with inability to tolerate oral intake. She presented due to worsening symptoms. She has no significant past medical history. Her past surgical history includes two c-sections and Lasik eye surgery. Her family history was noncontributory to the present illness. She has a sulfa allergy and is a nonsmoker, nondrinker.

Her vital signs were within normal limits on arrival. On physical exam (PE) she had localized tenderness in the RUQ and epigastric regions, with mild distention. She did not have rebound or guarding. Murphy’s sign was positive. No signs of peritonitis.

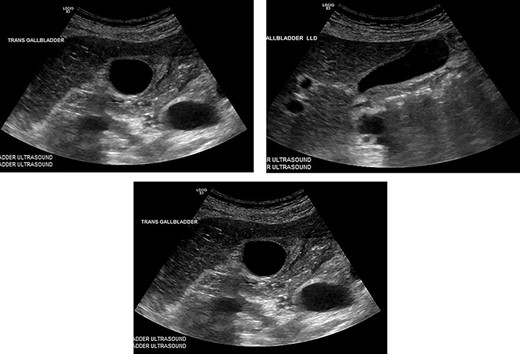

Hematology panel showed a WBC of only 7.6, H&H of 9.0 and 28.9, respectively. BMP was only significant for potassium of 3.4, all other values were normal. The patient had an RUQ ultrasound showing a thickened gall bladder wall at 4.5 mm, small amount of pericholecystic fluid. There were no gallstones and the common bile duct was within normal caliber (Figs 1–3).

These are from the patient’s ultrasound in the ER. The gall bladder wall was measured at 4.5 mm, and a small amount of pericholecystic fluid was present. There were no gallstones and the common bile duct was within normal caliber.

The diagnosis of cholecystitis was made based on history, PE, and findings on ultrasound and the patient was taken to the OR later that day for laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

Operation

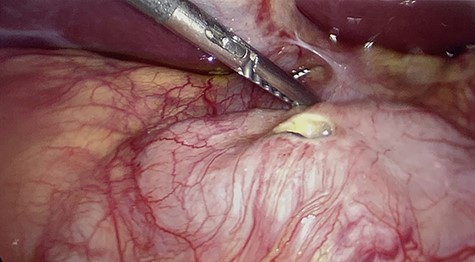

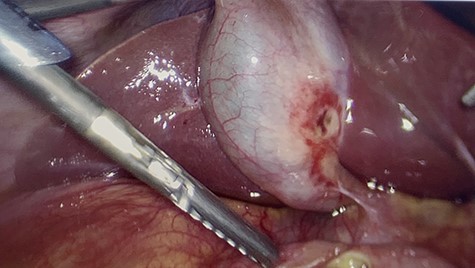

All of the standard preoperative measures were taken and the patient was prepped and draped for laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Ports were placed in a typical fashion for this operation, with A 12 mm Hasson trocar placed in a supraumbilical position, and 5 mm trocars placed in the epigastrium and RUQ x2. Upon insertion of the laparoscope, the uterus was still large in the pelvis and there was a small amount of bloody fluid in the abdomen. The fundus of the gallbladder was grasped and retracted cephalad. With this maneuver it appeared that the duodenum had fused itself to the infundibulum of the gallbladder. Upon gently peeling the duodenum off of the gallbladder, it became obvious that there was a perforated duodenal in the first portion of the anterior duodenum and had been the gallbladder that sealed the perforation (Figs 4–6). The gallbladder showed signs of erosion at the site where it patched the duodenum as well (Fig. 6). At this time we proceeded with laparoscopic cholecystectomy first, prior to addressing the duodenum. Once successfully completed with the cholecystectomy, we performed a laparoscopic graham patch with our existing ports, which can be seen in Fig. 7. A #10 flat JP was inserted in the region of the graham patch. The abdomen was irrigated and then suctioned clean. The repair was confirmed by placing underwater with the second portion of the duodenum compressed, while anesthesia insufflated the stomach/duodenum through an OG tube. The patient tolerated the operation well, extubated, and transported to recovery.

First portion of duodenum with perforated ulcer. Gallbladder retracted out of frame.

The gallbladder had been gently resected from the duodenum revealing a nonperforated ulceration where it had been patching the duodenal ulcer.

Image of completed laparoscopic graham patch over the duodenal perforation.

Postoperative course

Postoperatively the patient did well. She resumed a diet on postoperative Day 2 and was discharged on postoperative Day 4. Prior to discharge, the JP drain was removed, her pain was under control, she was ambulating without difficulty, tolerating a diet, and had remained afebrile. The final pathology report of the gallbladder showed chronic cholecystitis.

DISCUSSION

In this case, a postpartum woman with signs/symptoms, ultrasound findings and PE consistent with acute cholecystitis was taken to the OR for cholecystectomy. Intraoperatively, we saw the perforated duodenal ulcer, which had been sealed by the gallbladder. The gallbladder itself showed signs of erosion at the site where it had been in contact with the ulcer. The authors believe that we were visualizing an impending CDF.

Peptic ulcer disease (PUD) in pregnancy is a relatively uncommon phenomenon [1]. The diagnosis is complicated by the symptomology (nausea, vomiting, epigastric pain), which are common throughout pregnancy. Another theory about the decrease in incidence is due to the increased secretion of gastric mucus as a result of increased progesterone levels [2]. There is also noted decreased interventional diagnostic endoscopy in pregnancy women with PUD because of the increased risk of perforation, infection and bleeding [3]. In our patient, it is possible that pre-existing PUD was exacerbated by 5 days of continuous NSAID usage after her C-section.

The clinical presentation of both gallbladder disease and PUD are very similar, however perforated ulcers typically present with more severe symptoms. Though there are reported cases of simultaneous cholelithiasis/cholangitis with perforated duodenal ulcers, the diagnosis is often missed initially due to conflation of symptoms [4]. Bilio-enteric fistulas are often the result of chronic cholelithiasis pathology, and can result in the development of many types of communications to the gallbladder. In particular, CDFs are abnormal connections between the gallbladder and duodenum and are the most common type of fistulas [5].

As surgeons we see the manifestations of CDF once it evolves into a gallstone ileus. At that time, a fistula has already been created. The pathophysiology of CDF formation is unclear, however the conventional teaching is that gallstones erode through the gallbladder wall and fistulize with the duodenum [6]. The authors propose that had this patient been left untreated, a fistula would have formed secondary to perforated duodenal ulcer and not erosion of gallstones. While there have been documented case reports in the existing body of literature [6–9], the data on PUD as a cause of CDF are very limited. It is possible that the incidence of CDF formation secondary to perforated duodenal ulcers is underestimated.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

FUNDING

None.