-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Adam O’Connor, Fallon John, Shariq Sabri, Acute appendicitis located within Amyand’s hernia—a complex case with concurrent acute cholecystitis, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2020, Issue 12, December 2020, rjaa447, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaa447

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Amyand’s hernia is the presence of the vermiform appendix within an inguinal hernia sac. It is rare, and even rarer is the presence of acute appendicitis within the sac. It presents in a variety of different ways and often is only diagnosed intra-operatively. We present the case of a 90 year old male with extensive co-morbidities presenting with right upper quadrant pain, who on computed tomography scan of the abdomen, had acute cholecystitis alongside acute appendicitis within Amyand’s hernia. Ultimately given his co-morbidities, a conservative approach with prolonged antibiotic therapy was adopted, with a successful outcome. This case highlights that although classifications for treatment of Amyand’s hernia exist, careful clinical assessment is warranted in each case to ensure optimal outcome based upon individual circumstances.

INTRODUCTION

Amyand’s hernias are rare subtypes of inguinal hernias whereby the vermiform appendix is present within the hernial sac. They occur in just 1% of inguinal hernias. Even rarer is the presence of acute appendicitis within the Amyand’s hernia [1]. They can be difficult to diagnose pre-operatively unless imaging is performed. Hence intra-operative diagnosis is common. We present the case of a 90 year old male admitted with right hypochondrium pain and raised inflammatory markers whose computed tomograph (CT) scan of the abdomen ultimately demonstrated an Amyand’s hernia with acute appendicitis alongside acute cholecystitis. Given his co-morbidities and lack of symptoms in the inguinal region, the patient was managed conservatively with antibiotics with a good outcome.

CASE REPORT

A 90 year old gentleman was admitted on the acute surgical take with right hypochondrium pain. On examination he was pyrexial, tachycardic markedly tender in the right upper quadrant of his abdomen. There was also a reducible non-tender right-sided inguinal hernia present. His past medical history included atrial fibrillation (anti-coagulated with apixaban) alongside ischaemic heart disease, osteoarthritis and a degree of congestive cardiac failure with poor exercise tolerance. On further questioning he had noticed the lump for several weeks but described no tenderness around the lump. Blood workup revealed c-reactive protein of 140 mg/L and white cell count of 15 × 109. He had mildly deranged renal function at baseline consistent with an element of chronic kidney disease. Other blood tests were unremarkable. A diagnosis of acute cholecystitis was made with an incidental finding of right-sided inguinal hernia. He was commenced on intravenous antibiotics and CT scan of the abdomen arranged to ensure no co-existent pathology given his age. CT scan revealed the presence of a right-sided inguinal hernia containing a thickened vermiform appendix with peripheral fat stranding suggestive of acute appendicitis within an Amyand’s hernia (Figs 1 and 2). Additionally, the scan did confirm the concurrent presence of acute uncomplicated cholecystitis. Senior surgical and anaesthetic discussions took place with regards to operating on this patient to treat his appendicitis and repair his hernia. It was universally agreed that the acute cholecystitis could be viably treated with intravenous antibiotics in the interim. However, acute appendicitis, with its risk of complications, warranted further discussion. Following discussion with the patient, consultant physicians, anaesthetists and surgeons, the decision was made to treat both conditions conservatively with antibiotics. The rationale for this was that the patient’s main complaint was that of right upper quadrant pain. He did not have any peritonism or tenderness to his right inguinal canal that would suggest impending perforation or peritonitis. His co-morbidities and age undoubtedly made him a high-risk case for appendicectomy and hernia repair. Most importantly, the patient himself was very reluctant to undergo operation and had full capacity to make this decision, having been made well aware of the risks of not intervening. Ultimately, following a 12 day stay with intravenous antibiotics, physiotherapy input and input from the physicians, he was discharged and to date has suffered no complications of his hernia or gallstone disease.

Axial CT scan demonstrating right-sided inguinal hernia with vermiform appendix located within it, suggestive of Amyand’s hernia.

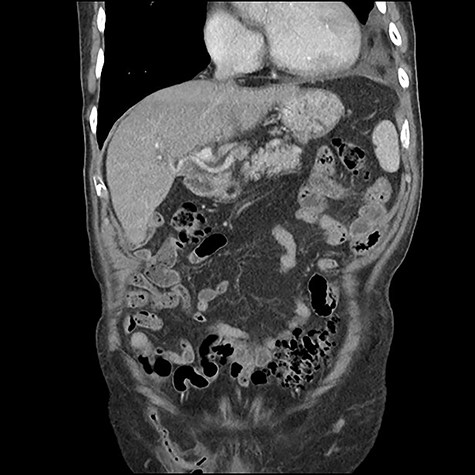

Coronal CT scan demonstrating appendicitis located within the inguinal canal.

DISCUSSION

Amyand first described his eponymous hernia in 1735 when operating on a paediatric patient with an inguinal hernia containing the vermiform appendix [1]. The incidence of Amyand’s hernia is around 1% of all inguinal hernias, with this dropping to 0.1% if there is acute appendicitis present within the hernial sac [2]. The majority of cases are right sided but case reports have described occurrence in the left side of the abdomen [3]. Their clinical presentation is varied, ranging from asymptomatic as in our case, through to presentation as an incarcerated inguinal hernia [4]. Uncommonly, Amyand’s hernia can mimic acute scrotal pathology such as torsion or abscess [5]. With regards to acute appendicitis occurring inside the sac, either primary appendicitis can occur or prolonged incarceration of the appendix and pressure from the abdominal wall leads to inflammation of the appendix [6].

There is no clear consensus into the optimal treatment of Amyand’s hernia. Some surgeons advocate appendicectomy and hernia repair in all cases even in spite of no abdominal symptoms, in order to prevent future complications from appendicitis. However surgeons opposing this point of view regard the appendix as useful in terms of paediatric immunity and in adults, feel that risks of the procedure outweigh the benefits given the low incidence of appendicitis in Amyand’s hernias [7]. Indeed in our case, the risk of any operation and subsequent general anaesthetic in a patient with cardiac co-morbidities and anticoagulation would certainly outweigh the benefit given lack of right iliac fossa symptoms and a soft, non-tender hernia.

Losanoff and Basson attempted to categorize Amyand’s hernia and provide a treatment algorithm for it. Type 1 hernias involve a normal appendix within the hernia sac and warrant mesh repair with reduction of the appendix. Type 2 hernias involve an acutely inflamed appendix but lack of abdominal sepsis, meriting appendicectomy with suture repair of the hernia. Type 3 involves a perforated appendix and Type 4 appendicitis within the inguinal hernia and concurrent abdominal pathology. Types 3 and 4 are treated with suture repair of the hernia and appendicectomy, with investigation of the abdominal pathology also warranted in Type 4 [8]. Our patient therefore had a Type 4 hernia. As mentioned, he was not acutely unwell from an appendix perspective and therefore actually needed broad-spectrum antibiotics to treat his concurrent cholecystitis. This case highlights that although such a classification is helpful, Amyand’s hernias presenting acutely should be clinically assessed on an individual basis.

To conclude, Amyand’s hernias are rare and present in a highly varied manner. Diagnostic vigilance is essential by ensuring examination of the hernial orifices in all patients presenting with an acute abdomen. Although classification systems exist, we propose assessing each case on its own merit based on the patient’s co-morbidities. In our case, although appendicectomy and suture mesh repair would have been the ideal, management with intravenous antibiotics treated both conditions simultaneously and effectively.