-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Brian Dusseau, Bridget Onders, Andrei Radulescu, Matthew Abourezk, John Leff, Metastatic melanoma of the spleen without known primary, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2020, Issue 12, December 2020, rjaa456, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaa456

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

We present the case of a patient who underwent a laparoscopic splenectomy for splenomegaly associated with anemia and thrombocytopenia thought to be secondary to lymphoma and was found to have metastatic melanoma without a primary source. This is a rare entity in that the patient falls into an atypical population group with conflicting opinions about management that has been scarcely reported in the literature.

CASE PRESENTATION

Melanoma is a malignant neoplasm that originates in melanocytes and is most commonly found in the skin and mucous membranes [1]. The primary lesion can propagate metastases throughout the body. The most common location for first metastases of malignant melanoma is the skin (38%), lung (36%), liver (20%) and brain (20%) [2]. In general, primary tumors and metastatic disease to the spleen is rare, often occurring late in the course of disease. Although it is the most vascular organ in the body, it is an infrequent site for metastatic disease [3].

Splenic metastases of malignant melanoma are usually found in cases of disseminated disease in which there are multiple viscera involved. At autopsy, 32–88% of patients who died of metastatic melanoma are found to have lesions involving the spleen [4]. However, solitary metastases to the spleen from malignant melanoma are rare, with only 13 previous cases being presented in the literature to our knowledge, and with only a single previous case presenting as a single lesion in the spleen later found to contain metastatic melanoma from an occult primary site [4, 5].

Our case presentation involves a 79-year-old male with a past medical history of hypertension, basal and squamous cell carcinomas status post excision who was found to have metastatic melanoma of the spleen without a known primary melanoma after splenectomy for symptomatic splenomegaly associated with anemia and thrombocytopenia. Before presentation our patient started to experience early satiety, 22 pounds unintentional weight loss and increasing fatigability. He presented to his primary care physician’s office and was found to have splenomegaly. The results of his initial lab work demonstrated anemia with a hemoglobin of 7.1 g/dL, thrombocytopenia with platelets of 46 K/mcL as well as hyperbilirubinemia of 3 mg/dL units.

The patient underwent a computed tomography (CT) abdomen pelvis as an outpatient, revealing splenomegaly measuring 18 × 9 × 5 cm (Fig. 1). The patient was subsequently admitted to our facility for the evaluation of his anemia secondary to what was thought to be a likely hematologic malignancy. The patient underwent a bone marrow biopsy, which demonstrated hypercellularity and erythroid hyperplasia with unremarkable cytogenetic markers and no evidence of myelodysplastic syndrome.

CT abdomen and pelvis axial images demonstrating splenomegaly measuring 18.4 × 9.4 × 15.8 cm.

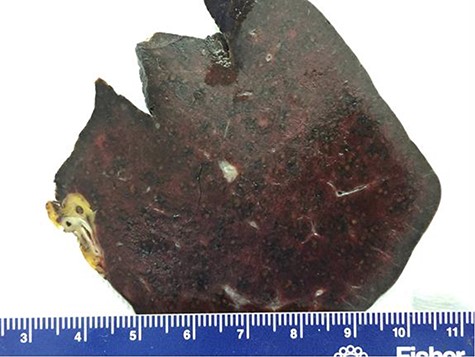

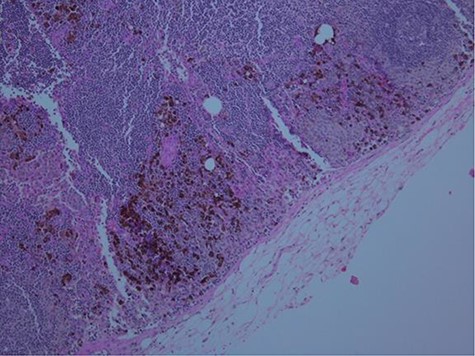

Following the results of the biopsy, the patient was referred to the oncology service where the diagnosis of splenic lymphoma was proposed, and the patient was referred to us for splenectomy. He subsequently underwent an uncomplicated hand-assisted laparoscopic splenectomy. Gross pathological examination demonstrated a deeply pigmented spleen (Fig. 2), and histopathologic examination of the spleen revealed positive staining for HMB-45 (Fig. 3), S-100 and Ki-67 suggestive of metastatic melanoma. This diagnosis was confirmed by a quaternary medical center that also examined the specimen.

Gross formalin-fixed pathological specimen fragment with deeply pigmented melanocytes.

The patient’s postoperative course was relatively uneventful with the exception of a mild ileus and was discharged on post-operative Day 4. Following his discharge and recovery, he was seen by the dermatology service that performed an extensive dermatologic examination including ocular and anal examinations and was found to have no lesions suggestive of a primary melanoma. Several suspicious lesions were biopsied during the exam and were examined by multiple pathology departments including one specializing in melanoma, and no primary lesion was identified.

The patient subsequently underwent a positron emission tomography (PET) CT and a magnetic resonance imaging of the brain, which were negative for metastatic disease. Given the lack of specific guidelines in this unique clinical situation, a multidisciplinary team discussion was held with the patient. The patient was presented with chemotherapeutic treatment options as well as a PET CT surveillance option, which the patient ultimately elected to pursue given the side effect profile of the available chemotherapy regimen. The first surveillance PET CT that was performed approximately 6 months post-operation revealed a hypermetabolic liver lesion that was biopsied and found to be v-raf murine sarcoma viral oncogene homolog B1, BRAF, positive metastatic melanoma. Post-operatively the patient elected to participate in BRAF inhibitor therapy utilizing vemurafenib and dabrafenib, which he has had no evidence of disease progression over the last 2 years.

DISCUSSION

Splenic melanoma metastases are a rare clinical entity and are often only seen when metastatic disease is widespread and solitary lesions to the spleen are exceedingly more uncommon. When isolated lesions are found in the spleen, they are often linked to a previously diagnosed primary melanoma lesion. This patient’s case exhibits a unique presentation of metastatic melanoma without a known primary lesion. Only one previous case has been documented as solitary metastatic melanoma lesion of the spleen [4]. A similar case was reported by Onan et al., who describe a 31-year-old male patient with no previously diagnosed primary melanoma who was found to have a right atrium metastatic melanoma lesion. In this patient, a postoperative workup revealed a gallbladder lesion as well as a primary [6].

The rarity of solitary splenic melanoma metastases is significant, with only an estimated 2% of cases of malignant melanoma falling into this category [7]. In addition to the rarity of solitary splenic metastases, there are scant mentions of cases of metastatic melanoma without a known primary lesion in the literature. It is estimated that only 3.2% of all metastatic melanoma cases do not have a known primary lesion [8]. Taking into consideration the rarity of both of these factors independently, the case of a solitary metastatic splenic lesion in melanoma without a known primary lesion is not encountered often.

CONCLUSIONS

We report an unusual case of a metastatic splenic melanoma without a known primary lesion in a previously healthy patient. This is a rare entity that has been scarcely reported.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We would like to thank Dr Charles Nicely MD from the Department of Pathology at Riverside Methodist Hospital for his expertise in preparing and interpreting the histological slides as well Dr Peter Kourlas MD of Columbus Oncology and Hematology Associates with his expertise regarding this patient’s unique oncologic and hematologic clinical presentation.