-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Yewon Kim, Paul Ghaly, Jim Iliopoulos, Gregory J Leslie, Mehtab Ahmad, Management of an inflammatory abdominal aortic aneurysm causing ureteric obstruction: a case report, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2020, Issue 11, November 2020, rjaa457, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaa457

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Inflammatory abdominal aortic aneurysms (IAAAs) are rare large-vessel pathology, with potentially life-threatening complications including obstructive uropathy secondary to retroperitoneal fibrosis. Comprising a small proportion of all AAA, their pathogenesis remains unknown, with the hypothesis of infective and immunological aetiologies circulating in current literature. Management principles of IAAAs aim at prevention of aortic rupture and include open-surgical or endovascular therapies. Due to their involvement of other structures, additional considerations are needed when approaching their management for optimal patient outcomes.

We present the case of a 53-year-old otherwise healthy male with a large IAAA complicated by adjacent ureteric obstruction, successfully treated with ureteric stenting and delayed endovascular aortic aneurysm repair.

INTRODUCTION

Inflammatory abdominal aortic aneurysms (IAAAs) are a rare, life-threatening pathology accounting for 2.2 to 18.1% of all abdominal aortic aneurysms (AAAs) [1]. Characterized by diffuse aortic wall thickening and associated retroperitoneal fibrosis, the diagnosis is often made incidentally on imaging. The rarity of IAAA has left the knowledge of its pathogenesis largely unknown. IAAAs present with symptoms more frequently than their non-inflammatory counterparts, with non-specific symptoms contributing to the difficulty in diagnosis. The prevention of aortic rupture is the common goal in the management of both conditions, however, IAAAs pose a management dilemma due to associated peri-aortic inflammation, increasing the risk of intraoperative injury to surrounding organs and critical anatomical structures. It is known that 30% of IAAA present with concurrent ureteric obstruction which poses an additional risk of acute kidney injury (AKI). Thus, when considering endovascular repair, additional consideration needs to be made for peri-operative optimization to mitigate additional morbidity from contrast-induced nephropathy. Prompt recognition and awareness of available treatment modalities is paramount to avoiding multi-organ injury or delays in treatment potentially resulting in aortic rupture.

CASE REPORT

A 53-year old male with no other past medical history of note presented to the emergency department (ED) with acute onset nausea and vomiting. This was preceded by a 2week history of non-specific malaise and generalized bilateral flank pain, worse on the right. He was an active smoker, with a 30-pack year history. He took no regular medications and had not undergone any previous surgical interventions. He denied any recent weight loss, night sweats or swollen glands.

On presentation, all baseline observations were recorded to be within normal parameters. Abdominal examination revealed right flank tenderness on both light and deep palpation with active bowel sounds and no palpable masses. Murphy’s sign was negative. His cardio-respiratory examination was normal, with no murmurs on auscultation or lower limb oedema.

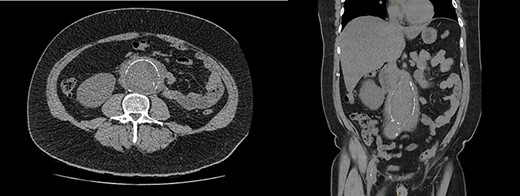

Blood tests demonstrated a severe AKI without significant neutrophilia but a mildly elevated C-reactive protein (Table 1). Given the flank tenderness and AKI, a non-contrast computed tomography of kidney, ureters and bladder (CT-KUB) was performed to exclude a renal or urological pathology. This demonstrated a large infra-renal AAA with surrounding retroperitoneal stranding and bilateral hydronephrosis (Fig. 1).

| Investigation . | Value . |

|---|---|

| Haemoglobin (g/L) | 114 |

| White cell count (cells/L) | 8.4 × 109 |

| Platelets (cells/L) | 276 × 109 |

| Sodium (mmol/L) | 142 |

| Potassium (mmol/L) | 5.0 |

| Chloride (mmol/L) | 102 |

| Bicarbonate (mmol/L) | 25 |

| Urea (mmol/L) | 21.8 |

| Creatinine (μmol/L) | 513 |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73m2) | 10 |

| Investigation . | Value . |

|---|---|

| Haemoglobin (g/L) | 114 |

| White cell count (cells/L) | 8.4 × 109 |

| Platelets (cells/L) | 276 × 109 |

| Sodium (mmol/L) | 142 |

| Potassium (mmol/L) | 5.0 |

| Chloride (mmol/L) | 102 |

| Bicarbonate (mmol/L) | 25 |

| Urea (mmol/L) | 21.8 |

| Creatinine (μmol/L) | 513 |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73m2) | 10 |

| Investigation . | Value . |

|---|---|

| Haemoglobin (g/L) | 114 |

| White cell count (cells/L) | 8.4 × 109 |

| Platelets (cells/L) | 276 × 109 |

| Sodium (mmol/L) | 142 |

| Potassium (mmol/L) | 5.0 |

| Chloride (mmol/L) | 102 |

| Bicarbonate (mmol/L) | 25 |

| Urea (mmol/L) | 21.8 |

| Creatinine (μmol/L) | 513 |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73m2) | 10 |

| Investigation . | Value . |

|---|---|

| Haemoglobin (g/L) | 114 |

| White cell count (cells/L) | 8.4 × 109 |

| Platelets (cells/L) | 276 × 109 |

| Sodium (mmol/L) | 142 |

| Potassium (mmol/L) | 5.0 |

| Chloride (mmol/L) | 102 |

| Bicarbonate (mmol/L) | 25 |

| Urea (mmol/L) | 21.8 |

| Creatinine (μmol/L) | 513 |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73m2) | 10 |

CT-KUB showing a large fusiform infra-renal AAA with moderate to severe retroperitoneal stranding (white arrow).

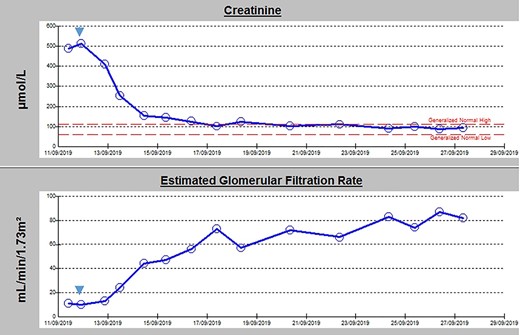

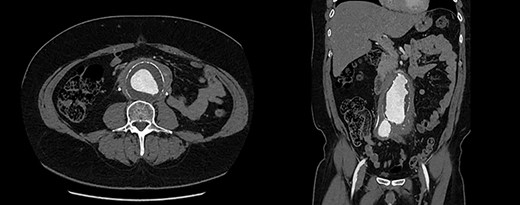

Urgent ureteric stenting to treat ureteric obstruction was performed with rapid normalization of renal function following stent insertion (Fig. 2). Upon normalization of his renal function, a contrast CT aortogram (CTA) was performed to delineate a 61 × 64 mm AAA, bilateral common iliac aneurysms (right 41mm × 44mm, left 31mm × 36mm) and associated peri-aortic stranding (Fig. 3).

Admission blood panel demonstrating an acute kidney injury with rapid normalization of renal function following insertion of bilateral ureteric stenting (timing indicated by blue arrow).

CTA demonstrating (A) a large 61mm × 63mm infrarenal AAA and (B) bilateral common iliac aneurysms (right 41mm × 44mm, left 31mm × 36mm).

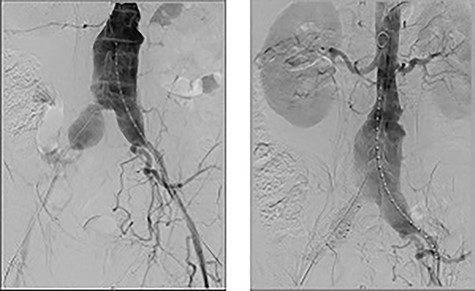

Extensive workup for infective and autoimmune aetiologies such as tuberculosis, syphilis, Q-fever and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) were negative and serum IgG-4 levels normal (Table 2). He underwent an endovascular aortic aneurysm repair (EVAR) with bilateral iliac branched devices (IBD) during his initial presentation, and his on-table completion angiogram demonstrated good flow through the grafts with no endoleak (Fig. 4).

| Investigations . | Value . |

|---|---|

| Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate (mm/h) | 109 |

| C-Reactive Protein (mg/L) | 44.6 |

| Lupus Anticoagulant | Positive |

| Rheumatoid Factor (international units/mL) | <13 |

| Cryoglobulin | Negative |

| Cardiolipin IgG (GPL) | 7 |

| Cardiolipin IgM (MPL) | 7 |

| Cyclic Citrullinated Peptide (units/mL) | 0.9 |

| Immunoglobulin A (g/L) | 2.21 |

| Immunoglobulin G (g/L) | 10.20 |

| Subclass IgG1 (g/L) | 8.29 |

| Subclass IgG2 (g/L) | 3.14 |

| Subclass IgG3 (g/L) | 0.38 |

| Subclass IgG4 (g/L) | 1.82 |

| IgM (g/L) | 0.71 |

| Serum Electrophoresis | |

| Albumin (g/L) | 41 |

| Alpha 1 Globulins (g/L) | 3.3 |

| Alpha 2 Globulins (g/L) | 12.6 |

| Beta Globulins (g/L) | 7.4 |

| Gamma Globulins (g/L) | 13.5 |

| Hepatitis B Surface Antigens | Negative |

| Hepatitis B Surface Antibodies | Negative |

| Hepatitis C Antibodies | Negative |

| HIV (1 and 2) Antibodies | Negative |

| TB Interferon Gamma Assay | Negative |

| Streptolysin O Serology (international units/mL) | 29 |

| Anti-DNase B (international units/mL) | 200 |

| Syphilis Enzyme Immunoassay | Negative |

| Investigations . | Value . |

|---|---|

| Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate (mm/h) | 109 |

| C-Reactive Protein (mg/L) | 44.6 |

| Lupus Anticoagulant | Positive |

| Rheumatoid Factor (international units/mL) | <13 |

| Cryoglobulin | Negative |

| Cardiolipin IgG (GPL) | 7 |

| Cardiolipin IgM (MPL) | 7 |

| Cyclic Citrullinated Peptide (units/mL) | 0.9 |

| Immunoglobulin A (g/L) | 2.21 |

| Immunoglobulin G (g/L) | 10.20 |

| Subclass IgG1 (g/L) | 8.29 |

| Subclass IgG2 (g/L) | 3.14 |

| Subclass IgG3 (g/L) | 0.38 |

| Subclass IgG4 (g/L) | 1.82 |

| IgM (g/L) | 0.71 |

| Serum Electrophoresis | |

| Albumin (g/L) | 41 |

| Alpha 1 Globulins (g/L) | 3.3 |

| Alpha 2 Globulins (g/L) | 12.6 |

| Beta Globulins (g/L) | 7.4 |

| Gamma Globulins (g/L) | 13.5 |

| Hepatitis B Surface Antigens | Negative |

| Hepatitis B Surface Antibodies | Negative |

| Hepatitis C Antibodies | Negative |

| HIV (1 and 2) Antibodies | Negative |

| TB Interferon Gamma Assay | Negative |

| Streptolysin O Serology (international units/mL) | 29 |

| Anti-DNase B (international units/mL) | 200 |

| Syphilis Enzyme Immunoassay | Negative |

| Investigations . | Value . |

|---|---|

| Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate (mm/h) | 109 |

| C-Reactive Protein (mg/L) | 44.6 |

| Lupus Anticoagulant | Positive |

| Rheumatoid Factor (international units/mL) | <13 |

| Cryoglobulin | Negative |

| Cardiolipin IgG (GPL) | 7 |

| Cardiolipin IgM (MPL) | 7 |

| Cyclic Citrullinated Peptide (units/mL) | 0.9 |

| Immunoglobulin A (g/L) | 2.21 |

| Immunoglobulin G (g/L) | 10.20 |

| Subclass IgG1 (g/L) | 8.29 |

| Subclass IgG2 (g/L) | 3.14 |

| Subclass IgG3 (g/L) | 0.38 |

| Subclass IgG4 (g/L) | 1.82 |

| IgM (g/L) | 0.71 |

| Serum Electrophoresis | |

| Albumin (g/L) | 41 |

| Alpha 1 Globulins (g/L) | 3.3 |

| Alpha 2 Globulins (g/L) | 12.6 |

| Beta Globulins (g/L) | 7.4 |

| Gamma Globulins (g/L) | 13.5 |

| Hepatitis B Surface Antigens | Negative |

| Hepatitis B Surface Antibodies | Negative |

| Hepatitis C Antibodies | Negative |

| HIV (1 and 2) Antibodies | Negative |

| TB Interferon Gamma Assay | Negative |

| Streptolysin O Serology (international units/mL) | 29 |

| Anti-DNase B (international units/mL) | 200 |

| Syphilis Enzyme Immunoassay | Negative |

| Investigations . | Value . |

|---|---|

| Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate (mm/h) | 109 |

| C-Reactive Protein (mg/L) | 44.6 |

| Lupus Anticoagulant | Positive |

| Rheumatoid Factor (international units/mL) | <13 |

| Cryoglobulin | Negative |

| Cardiolipin IgG (GPL) | 7 |

| Cardiolipin IgM (MPL) | 7 |

| Cyclic Citrullinated Peptide (units/mL) | 0.9 |

| Immunoglobulin A (g/L) | 2.21 |

| Immunoglobulin G (g/L) | 10.20 |

| Subclass IgG1 (g/L) | 8.29 |

| Subclass IgG2 (g/L) | 3.14 |

| Subclass IgG3 (g/L) | 0.38 |

| Subclass IgG4 (g/L) | 1.82 |

| IgM (g/L) | 0.71 |

| Serum Electrophoresis | |

| Albumin (g/L) | 41 |

| Alpha 1 Globulins (g/L) | 3.3 |

| Alpha 2 Globulins (g/L) | 12.6 |

| Beta Globulins (g/L) | 7.4 |

| Gamma Globulins (g/L) | 13.5 |

| Hepatitis B Surface Antigens | Negative |

| Hepatitis B Surface Antibodies | Negative |

| Hepatitis C Antibodies | Negative |

| HIV (1 and 2) Antibodies | Negative |

| TB Interferon Gamma Assay | Negative |

| Streptolysin O Serology (international units/mL) | 29 |

| Anti-DNase B (international units/mL) | 200 |

| Syphilis Enzyme Immunoassay | Negative |

On table completion angiogram demonstrating good flow through the stent graft and satisfactory flow through renal arteries and iliac branching device with no endoleak.

Post-aortic stenting, a percutaneous US-guided biopsy of the para-aortic fibrosis was obtained for histopathological evaluation. Results reported non-specific fibrous tissue with chronic inflammation and no features of granulomatous inflammation or malignancy. He was subsequently discharged on Day 8 post-EVAR and on 30-day follow-up, a repeat CTA showed all grafts remained patent with no evidence of endoleak or evidence of aneurysmal enlargement. He subsequently had his ureteric stents removed, with continued normalization of renal function, and was referred to a rheumatology specialist for ongoing management of suspected systemic IgG-4 related disease.

DISCUSSION

IAAAs are a rare subtype of AAAs with atherosclerotic being the most common. Therefore, traditional approaches to treatment are derived from the general principles of management of atherosclerosis-related AAA disease. The average annual risk of rupture for a 60 mm infra-renal AAA is ~10%, and at that size, AAAs are considered to have surpassed the accepted threshold size for intervention (55 mm) [2, 3]. IAAAs have a lower lifetime risk of rupture, at 5%, however they are typically more symptomatic with presentations ranging from abdominal or back pain, weight loss and fevers [4].

Clinical and radiological features of IAAA overlap with other aetiologies such as mycotic AAA, however, their management widely differs. Consequently, a confident diagnosis of IAAA requires thorough exclusion of mycotic AAA through microbiological investigations with blood cultures and testing for tuberculosis and syphilis prior to treatment [5].

Currently, there is a lack of clear evidence regarding the optimal approach to management of IAAA, with both medical and surgical management utilized in the literature. Medical management involves the use of anti-atherosclerotic therapies in combination with immunosuppressive agents such as steroids, methotrexate and azathioprine. The role of medical management alone is currently restricted to symptomatic patients with aneurysms smaller than the threshold indicating repair and patients in whom operative management is contraindicated [5]. However, the optimal agents, doses and durations of therapy are unclear due to the lack of controlled clinical trials. Operative management is indicated for aneurysms great than 55 mm and refractory cases not controlled by medical management [6].

Surgical options for IAAA repair include open and endovascular approaches. Characteristically, IAAAs are frequently complicated by inflammatory adhesions from retroperitoneal fibrosis involving local structures, increasing the potential for iatrogenic injury in open surgical repair. At-risk organs include the duodenum, left renal vein, inferior vena cava and ureters. Endovascular repair has generally superseded open surgical repair for this reason, with proven lower associated 30-day mortality and complication rates and a lower 1-year all-cause mortality compared to open repair (1% vs. 14%) [7].

Our case was complicated by hydronephrosis secondary to retroperitoneal fibrosis resulting in an AKI. Obstructive uropathy occurs in ~30% of IAAA, highlighting the importance of rapid recognition and intervention [4]. The rationale for treating the obstructive uropathy and AKI prior to endovascular repair was 2-fold. Firstly, it allowed peri-operative optimization of organ function. Furthermore, due to the severity of AKI, it was felt necessary to treat prior to endovascular repair of the AAA to mitigate the effects of contrast-induced nephropathy.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.